It’s probably good news when the only item you need to fit to a 44 year old British bike is a bicycle bell. John Whapshott tells a rider’s tale

Like many Marters before, I reluctantly packed away my crash helmet soon after I got married twenty years ago. Mary and I both liked bikes, and for a time an A7 was our only means of transport, but then – well, you know how these things go!

Anyway, last May we felt that the time was right to cover the patio in oil and fill the front room with unidentifiable bits of metal, so it was time for The New Bike!

But what would we get? (OK, if you’ve read the heading you’ll know, but bear with me). Since we could only afford one bike, it had to be right for everything I wanted it for. So my thinking went roughly like this: it had to be powerful enough to get me and the wife round the local lanes and roads, and be able to handle the odd long-distance run (ie anything beyond the next town), which meant a minimum capacity of 500cc; I wanted a bike with an alternator, because I was still in therapy from the magneto and dynamo tricks played on me by various Beezas; I wanted a single, for the ludicrous reason that there wouldn’t be so many spares to buy (oh come on – I’d been out of biking for 18 years!); I didn’t mind unit or non-unit construction; and I had a budget of around £2000 (plus almost the same again for the clothing, I discovered! In my youth protection against elements, tarmac and Volvos was afforded by a polycarbonate lid, Parka and jeans…).

I looked at several machines which did and didn’t fit the bill. I enjoyed a spin on a B50, but its 10:1 cr meant that it could only be started by someone with the build of Jonah Lomu; a B44 was nice, but a word from Frank put me right (the word was Don’t!); a beautiful 1972 Lightning was in the right price range, as was an Ajay 650 twin, but I realised that in the intervening years these bikes had put on an awful lot of weight (so had I – sigh…). And a Daytona at my local Modern Bike Emporium looked very nice – until it was started, at which point I realised that someone had seemingly connected the oil tank directly to the cylinder head. When I pointed this out to the bored proprietor in order to negotiate some sort of price reduction, he said ‘It’s a classic, priced to sell.’ To some other idiot, but not to this one!

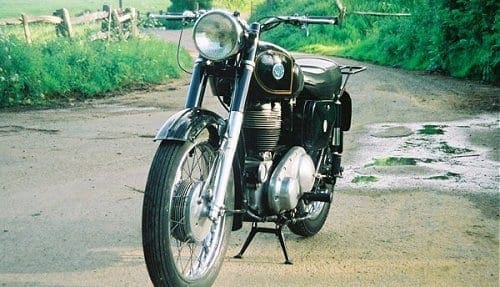

Then I noticed an ad in OBM for a nearby classic dealer, so off we trotted. Inside his shed were several wonderful bikes, including the subject of this piece. A close inspection and couple of test rides (as stipulated by Frank’s Big Book of Bikes for Boys And Girls) confirmed that it would be the ideal machine for us. The headlight assembly was from a later year, but that really didn’t bother me – it looked good and went well.

So did it live up to expectations? As John Major used to say to Edwina Currie, Oh yes! It was dead easy to start, thanks to its soft compression. The Man At The Dealers told me to fiddle about with the air screw on the carb before starting. I’d never come across this technique before, and when I passed this wisdom on to the editor of what was then The World’s Greatest Bike Mag, the message came racing back from Westworth Ho!: On No Account Touch The Air Screw On The Carburettor – Leave The Damn Thing Alone!! I found that the traditional method of opening the air lever and throttle a tad, using the valve-lifter to get it over compression and almost resting my foot on the kick-start produced the desired effect, viz. the bike started. Fortunately the silencer could be sued under the Trades Description Act, because the bike made the most wonderful noise!

On the road some vibration was apparent, but the controls fell easily to hand and foot (I am still worried by what one 50s road tester meant by ‘a bewadered foot’!). Continuing to avoid clichés like the plague, upward and downward gear changes were amazingly smooth, smoother than any BSA or Triumph I’d ever owned. No need for the ‘if you can’t find it, grind it’ style of gear-changing. The Model 18S had an AMC box, which was apparently superior to the Burman it had replaced in 1956. Whatever, it meant I could concentrate on advanced manoeuvres like going round corners rather than on whether I’d just stripped some teeth off the cogs every time I changed gear. Whoever had rebuilt this bike had made a wonderful job of it.

On the road it chuffed along happily in top from around 20mph to my mechanically-sympathetic maximum of about 60. A 1964 test of the same model claimed a top speed of 87mph – but it didn’t say how many men it took to pick up the pieces afterwards. The Ajay didn’t seem to mind whether my wife was on the back or not (nor did I…) – whether one- or two-up, it just plodded along in its own 1950s world, slow but sure. Not that I had wanted some massive mile-eater. The 18S delivered exactly what I had bought it for: leisurely, enjoyable progress.

The brakes. Well, what do you expect from a 1950s bike? They stopped the bike reasonably well, but anticipation was necessary in traffic. Actually, someone with the ability of a precog would have been more useful (did you spot the fatal flaw in the plot of Minority Report?), since motorists in the Guildford area tended not to give advance warning of stupid / dangerous / pointless manoeuvres. Maybe in future editions of The Highway Code there will be a car drivers’ hand-signal for I Am About To Do Something So Spectacularly Homicidal They Will Send Me To Iraq To Do It In The Streets Of Baghdad And Bring Saddam To His Knees. There is certainly a hand-signal which can be used by victims of such performances…

The brakes. Well, what do you expect from a 1950s bike? They stopped the bike reasonably well, but anticipation was necessary in traffic. Actually, someone with the ability of a precog would have been more useful (did you spot the fatal flaw in the plot of Minority Report?), since motorists in the Guildford area tended not to give advance warning of stupid / dangerous / pointless manoeuvres. Maybe in future editions of The Highway Code there will be a car drivers’ hand-signal for I Am About To Do Something So Spectacularly Homicidal They Will Send Me To Iraq To Do It In The Streets Of Baghdad And Bring Saddam To His Knees. There is certainly a hand-signal which can be used by victims of such performances…

Oh the joys of the open road!

Which leads me to the laughable horn. It was derided in tests of the period, and it hasn’t changed in all them years. So fit a bicycle bell, or an air-raid siren, or something to adequately express your dissatisfaction with users of four-wheels (apart from yourself, of course).

My bike had had a 12-volt conversion, I was told. Well, it had a 12-volt battery and some bits of paper explaining how the wiring went. But I soon discovered that the lights just made things darker. I couldn’t for the life of me see any difference between the alleged 12-volt lighting and the 6-volt pool of gloom I had come to love and ignore on earlier bikes (I once found that I could ride an A7 30 miles along a main road with no lights and no complaints from car drivers, presumably because they couldn’t see me).

Maintenance was fairly straightforward. In fact the most awkward thing was removing the spark plug, as the chappies at AMC who designed the tank hadn’t spoken to the engine chappies, with the result that you have to use a flexible plug-spanner to remove it. Fortunately I seemed to have had one in the bottom of one of my tool-boxes. The 18S liked regular oil changes, ie every 500 miles or so. Oh and another word of wisdom from He Who Knows: don’t bother with all that fancy expensive oil for yer everyday hack. The current multigrades are far superior to anything produced when the bikes were new. I bought my oil from Tesco, as the spiel assured me that it would lubricate Formula 1 cars without getting stressed. (More oil wisdom here…). So save your money for those spares!

Which I didn’t need. The Ajay was amazingly reliable, but I wasn’t. At the end of September I underwent a fairly minor operation, and had a very rare reaction to the combination of the pre-op drugs and the anaesthetic, which had a drastic effect on me, especially my legs. After a month of barely being able to walk, and with the realisation that getting astride anything was likely to take several months at least, the Ajay was reluctantly sold someone who would be able to ride it.

My verdict on the 18S? It was everything I had wanted – a good, solid, reliable bike for every day use and the occasional long journey; easy to work on; a joy to ride and a pleasure to own. When I rode it to work any number of colleagues would admire it and bring out reminiscences of similar bikes either they or their Dad had owned. Beats team-building exercises any day!

Now in March, I’m on the mend and looking forward to the day when I can get back in the saddle. I’ve seen an ad for what that same local classic dealer has in stock – some very nice bikes at very reasonable prices…