Thinking of buying a 750 Laverda twin? Dave Minton rings the changes between the models and offers shoppers well-proven advice…

In the first installment, Laverda introduced their 750 twin parallel twin and – against the odds – it proved to be one of the best. They could hardly keep up with customer demand it first, but by 1972 the competition was a lot hotter and it came with four cylinders.

So for 1973 Laverda’s 750 twin got the boost it needed, in the shape of the SF1. By this time sound level regulations were intruding so Laverda was faced with the conflicting difficulties of increasing gas flow and decreasing exhaust noise. Laverda achieved both ends with large diameter exhaust pipes (1.6-inch) interconnected by a transverse collector box, new style Dell Orto 36mm pumper carbs and a matching new camshaft. These mods lifted power to a claimed 66bhp at 7300rpm, and top speed rose accordingly to around 117mph.

The bike from particular year is generally regarded by afficianados as the quickest of the SFs. While their handling was heavy, although quite typical of the period, not much else cornered more sure-footedly than an SF.

Despite the apparently modest power increase, the SF1s were noticeably faster on nip-and-tuck riding. In the first place they were fitted with a single Brembo 11-inch disc front brake which, while no more powerful than the old drum, could be used repeatedly without fading. And in the second place, SF1 acceleration in normal highway use was undeniably superior to SF, thanks to a further lightened flywheel.

But the whacking great collector box beneath the bike was the problem, as any SF1 owner worth his salt soon discovered when riding through a series of bends. The thing grounded with all the eagerness of a pig after truffles, although with an appallingly amplified volume of squeal. Exhaust apart, you will also recognise this model by its squat little chromed CEV headlamp and bat-wing Lucas switchgear.

Then in 1974 came the SF2 where the SF engine reached the pinnacle of its road-going development, although not until ungagged did it breathe freely enough to realise its full potential, when with matching recarburation 120mph was available. Along with new Ceriani teles, Laverda doubled up on the front brake discs and replaced the rear drum with a single disc. Thankfully it exchanged the abominably manufactured Lucas switchgear for Nippon Denso’s Suzuki pattern. Another worthwhile change was to a black Bosch headlamp. However, like many low-volume production-run models, single items may migrate from one model year to the next, often as a result of the original purchaser’s personal specification. Thus the best way to date any bike is from its engine number rather than by its headlamp or braking equipment.

The SFs achieved their final form in the shape of the SF3 which arrived in 1976. The most obvious change was to the wheels which lost their wire spokes in favour of cast aluminium ones, although they remained suited to tubed tyres only. A lockable, hinged dual seat with a duck-tail box behind finished the revisions.

To give Laverda credit, it had added no weight during the eight years of 750 production, and a build and material quality superior to any of its competitors had been maintained. At a time when high speed stability and braking, most especially in the rain – which lubricated Japanese discs as well as oil – were all too frequently suspect, the SF range had proved equally superior.

But by 1977 the Big Four manufacturers had 750cc twin-cam fours listed. The best of these was Suzuki’s standard-setting GS750, which was priced at £1700, while the SF3, a mere twin, cost £1950.

Laverda experimented with an improved SF engine, narrowed by crankshaft compaction and lightened with an alternator and smaller starter motor, but by this time the 981cc twin-cam triple had become the centre of attraction. Production of all 750cc twin variants finally ceased in 1977 although sales continued into 1978. In total, 19,000 of these twins were produced in all.

So why did these bikes not become big sellers in Britain?

(1). They were imported by a small company, without major marketing experience or sufficient capital.

(2). British motorcyclists had been made suspicious of parallel twins.

(3). Laverda’s remarkable endurance racing successes with the twins made no impression on British motorcyclists.

(4). The SF was an expensive machine. In 1974 an SF cost £1250; a Kawasaki Z900 cost £1100.

These days, prices are rising steadily but you can still find SFs in superb condition (the ILOC’s magazine is a good place to start looking).

Laverda’s finish was excellent, with above-average paintwork, even if the chrome plating was a little thin. When they were new the twins suffered from a poor reputation over ‘corroding’ aluminium castings. The truth was that, as a non-ferrous foundry specialist, Laverda made its own castings to aircraft specification. This meant that it intentionally and uniquely left its castings unsealed from resin impregnation so they could exude otherwise locked-in impurities. Practically no-one believed this so the white dusting on long-term parked SFs was labelled ‘corrosion’. Check this by a quick finger wipe should you discover any white dust on a potential purchase. It should leave no trace apart from a light stain, easily polished away.

Inspect the brake drums and linkages of drum braked models. If the drums are scored and the fulcrums need re-bushing they can prove worrisome. Try the brakes in use: weak braking usually signifies incorrect maintenance rather than inherently bad brakes and they must be re-lined and set up by a drum brake specialist (see our Techniques feature on brakes for more info).

Ultra-heavy clutches can be simply lightened by carefully re-routing a well lubricated cable, and / or by fitting an extended gearbox lever. Both of these ‘faults’ can be used to excellent advantage in any price haggling.

Start the engine. Take heed over starter motor engagement because these items are unique to Laverda twins with no alternative source for a replacement. SFs should fire up quickly and idle reliably. Their mechanical sound levels are high by modern standards but not significantly worse than a Meriden Triumph twin. But beware of loud clattering which could have two origins; damaged pistons or rings, or badly worn cams. A few – very few – SFs have given slight piston trouble and a lack of frequent oil changes can cause cam scuffing.

You may also be tempted by a 750cc GT tourer. These 52bhp / 107mph machines were produced for the five years leading up to 1974, then the GTL was introduced. These employed the GT motor in the SF rolling chassis but with a bigger tank and touring handlebars. GTL production ceased in 1977 and very few were imported to the UK.

The GT was, and remains, one of the sweetest natured and most docile tourers imaginable. Thanks to their SF chassis, GTL handling is a little heavy but the simple installation of an SF camshaft transforms their performance, which their ultra-heavy touring flywheels tend otherwise to dampen. Despite the fact that only a small handful of GTLs were sold new in Britain, you will find them easy to obtain. They were sold by the factory to fleet users around the world, mainly as police machines.

Of all Laverda’s twins none are more misunderstood nor yet more commonly replicated than the 75bhp, 130mph SFCs. They were built with especially manufactured components in the factory competition department by race engineers specifically as endurance racers. They were not production racers, although many were adapted to this class of racing with immense success. The likelihood of discovering a cheap and forgotten SFC is zero: every one made is known to the International Laverda Owners’ Club. So if you do find one for sale then it is vital to have its authenticated before parting with any cash.

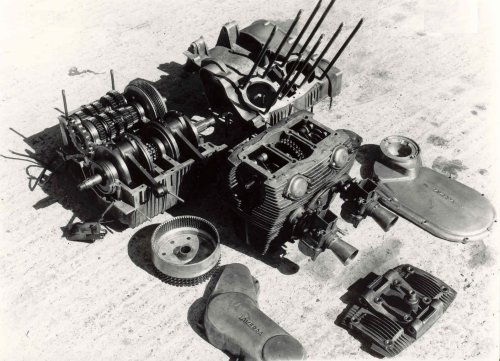

Once you have a 750 Laverda twin in your stable, by far the most important side of SF ownership is frequent oil changes of high grade oil. The engine shares the gearbox lubricant, but this is much less damaging than rumour has it. SFs have engines crammed with ball and roller bearings and these seriously stress oil, to an extent far exceeding that of gearbox teeth. Moreover, SFs have no true oil filter. These can be fitted by specialists but it’s not cheap. A satisfactory alternative is to fit a magnetic sump plug into the existing sump plate which will retain all the harmful steel swarf.

Although the Bosch contact breaker point ignition is about the best of its type, old Laverda specialists all offer electronic conversions. The most popular of these is the Boyer Bransden kit which greatly improves the engine’s manners.

Overall these models hide no serious faults and are generally easier to service than a BSA A10.

People To Speak To