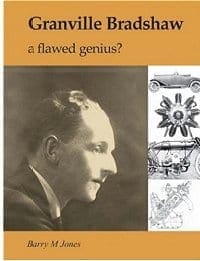

The man behind the popular Panther single was also responsible for various aero engines and the Sopwith ABC. Plus he had a passion for toroidal engine design. We enlisted an engineer, Jacqueline Bickerstaff, to read and unravel his life’s story…

A few days ago a large and heavy tome dropped through my letterbox, bearing a note saying ‘we wondered if you would fancy reviewing this’. Notwithstanding the 280 pages, it looked like being an interesting task, for the book is about Granville Eastwood Bradshaw, aero-engine and motorcycle designer extraordinaire, and one-time occasional contributor to ‘Motor Cycle’.

As suggested in the book title, Bradshaw is a controversial figure, as far as his designer status goes. Motorcyclists with a historical bent may recognise Bradshaw as the designer of the innovative, but short lived, 1920s ABC with its transversely mounted horizontally-opposed 400cc engine, the oil-cooled Bradshaw proprietary engine used by DOT and others, and possibly for a connection with P & M (Panther).

Those with a more aeronautical bent may be aware of Bradshaw’s WWI ABC ‘Dragonfly’ radial engine which was due for production in 1919, and of which it has been said that it would have lost the war for Great Britain and her allies had the war lasted that long. Against such snippets Granville Bradshaw has often been judged as anything from a failed designer to a fast-talking salesman and charlatan.

Finally, Barry Jones has given us a detailed study of Bradshaw’s incredible variety of designs and projects over a period of more than 50 years, to redress the balance a little.

The main source material for the book has been Granville Bradshaw’s own papers, and some excerpts from a lost autobiography, with further assistance from the family, and son Geoffrey in particular. Granville died in 1969 so these papers were incomplete and in disarray, leaving Barry to admit (in the chapters on toroidal engines, p216) that he has made the best job he could in trying to make that part of the story coherent. However, references in the text, a patent list, and the bibliography, also shows that Barry did considerable research outside of the Bradshaw family archive too, and this shows through clearly as the story unfolds.

Barry charts Bradshaw’s early work on pioneer flight, and the Star monoplane in particular, establishing himself as something of an expert on stressing, and a contemporary of Rolls and Cody. His work then progressed into engines, and the ABC company in particular, where he was a partner, and where the early in-line h-o twin ABC motorcycles were made.

Bradshaw’s 9-cylinder radial aero-engine design, the ABC Dragonfly, proved a failure. Much maligned as the aero-engine that would have lost the Great War, had it extended into 1939, Barry Jones’ book provides more detail of both the engine and the circumstances

However, ABC’s main focus was on aero engines, for which application Bradshaw designed a four, V8 and opposed twin engines amongst others. During the war years the company developed their 7-cylinder ‘Wasp’ radial, which was made in limited numbers, before entering the larger, and notorious, 9-cylinder ‘Dragonfly’ radial for the Air Board’s competition for a new, high power radial aero-engine. The Dragonfly promised high power and easy manufacture, with the prototype producing 365bhp on test, and not only won the competition, but was ordered prematurely into production, with the expectation of superseding all rotary/radials for 1919!

The engine was, indeed, something of a disaster, but Barry points out that the design was immediately taken out of ABCs hands and placed in those of the RAE. The worst problem was crankshaft resonance and failure, which in those days was not well understood or easily corrected, and was somewhat unexpected on a short, single row radial. RAE learned a lot about the subject. However, with the war ended, the Dragonfly development effort was not needed, and with hindsight it was labelled a disaster, and Bradshaw a charlatan, wheras in fact Bradshaw did a lot of fundamental research on aero engine problems.

Major GP Bulman, WWII Director of Engine Production (who was not the same man as Sopwith test pilot G Bulman, with whom Barry confuses him) is one who is credited with the oft repeated statement that the Dragonfly would have lost the war had it continued into 1919 (actually, in Major Bulman’s own autobiography it is apparent that it was the Air Board decision to put an untried engine into production that appalled him, and this remained a lesson learned for the rest of his career overseeing British aero-engine development for the Government).

Bradshaw’s most famous design, the Sopwith built 400cc transverse-twin ABC followed WWI, when demand for aero products fell away and companies needed to diversify. This motorcycle had some flaws, throwing away its pushrods being one example, but they were eminently curable as aftermarket companies showed. The Sopwith ABC made a big impression at the time, and one that has endured to this day. It is, however, often blamed for the downfall of the Sopwith company, but Barry explains more fully the pressures of the time, including a trend for Aero companies to voluntarily liquidate whilst still solvent, influenced by keeping the Ministry of Munitions at bay (who were not averse to clawing back war-profits).

Panther were a company that repetedly used Granville Bradshaw’s consultancy services. This 500cc parallel twin, with in-line engine, and contra-rotating cranks, was in development when WWII stopped play

The ABC company was itself reconstituted in 1920, at which point Bradshaw’s involvement changed to that of a consultant only, and he subsequently designed and sold his designs in this capacity where he could. It was in this period that he was involved with the Belsize-Bradshaw car, designed the ‘Oil-boiler’ engines (although Barry assures us that the engines never did boil their oil), and worked for Panther, designing their long-lived ohv engine. He also designed them their transverse V-twin ‘Panthette’ which clearly shows its Sopwith-ABC heritage when the book’s illustrations are compared. Readers will also discover a little-known parallel twin Panther using an in-line, contra-rotating crank engine, which was overtaken by WWII.

Bradshaw’s interests were not confined to aeroplanes and engines, and the book reveals his gambling machine patents and businesses that made Bradshaw a rich man. Unfortunately a business deal robbed him of his fortune again, so that all his post-war work was done with very limited resources. These post-war projects included working on the Bond minicars, made by Sharp’s Commercials (run by his brother Ewart) and designing a ‘people’s car’.

Barry Jones’ book takes the reader through a mesmerising list of Granville Bradshaw’s inventions and designs, surely enough to convince most people of the ‘genius’ part in the title. The book takes many a byway into the affairs of other companies, for whom Bradshaw did his consulting, or who used his engines, at least in part to indicate that the experts of the day certainly took his work seriously. These asides may be a little superfluous at times, but present an interesting insight into the aero and motor/motorcycling businesses of the times. There are some mistakes, such as the Bulman issue already mentioned (p111 & p254), and typos such as equating 1 bhp to 1.104 PS/CV instead of 1.014 (p155).

Barry’s engineering explanations sometimes leave a little to be desired (for example the explanation of Bradshaw’s bicycle ‘torque equaliser’ on p90 does not tally with the diagram presented). Barry also, not surprisingly, tries to show Bradshaw in a good light, and therefore quotes claims that he may know or suspect to be dubious, such as introducing the 1924 ABC Hornet as ‘Reputedly the world’s first horizontally opposed flat four aero-engine’ (p86), when, in reality, Geoffrey De-Havilland’s 1909 engine, produced by Iris Motor Co., and fitted to his own 1910 aircraft (amongst others) used a similar layout, albeit water-cooled. However, it is not a mechanical engineering text-book, so these are relatively minor issues.

The book outlines Bradshaw’s many inventions and products, but illustrates that few of them achieved real commercial success and so, perhaps, illustrating the ‘flawed’ part of the title. However, it also shows that many factors played their part, more usually lack of development resources rather than chicanery, and development and finance was all too often in the hands of customer organisations rather than Granville Bradshaw himself.

This is book for the technically minded, and for those who will delight in diagrams and engineering. It is not a story book, or even a life story as little is written about personal or family matters, although the endeavour, earlier successes, and the later decline in fortunes and disappointment is there to be discerned. But mostly the book is about ingenuity, inventiveness, and the designs that flowed so freely from Granville Bradshaw’s pen. In recent years much of this has been forgotten, with Bradshaw branded a designer of little consequence but much persuasiveness. ‘Granville Bradshaw; a flawed genius?’ reminds us of his capabilities and achievements, and of the ‘genius’ part. Barry Jones has researched widely to fill the book full of information and drawings, and as comprehensive a story about the man as we are likely to see.

Highly recommended reading, especially for the historically and mechanically minded.

Reviewed by Jacqueline Bickerstaff

—————

‘Granville Bradshaw: A Flawed Genius?’ by Barry M Jones is published by Panther Publishing and normally costs £19.95. It’s a 288-page softcover, with over 200 illustrations. ISBN 978-0-9556595-4-6.

Search for books and magazines on

Ebay.co.uk