Sold at the time as ‘the Italian Alternative’, this six-cylinder superbike from the 1970s still offers something radically different for the classic bike connoisseur…

In 1972 Benelli stole a march on the rest of the motorcycling world when they launched the first production six-cylinder bike, the 750 Sei. A few years later they brought its big brother to the UK, and RC reader Phil Colin was so smitten by the Benelli that he just had to own one. Phil bought his 900 Sei second-hand in 1985 – and then didn’t fire it up again for a quarter of a century!

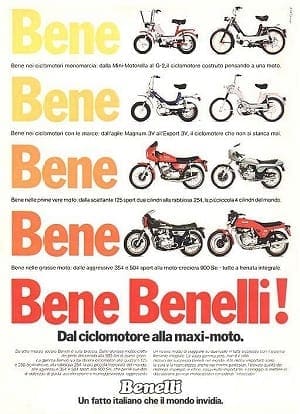

Back in the 1970s, Benelli’s range were based around a version of the Honda CB500 four-cylinder engine. To create the 750 they added an extra set of cylinders, and parked the alternator behind the block instead of leaving it hanging on the end of the crankshaft. This kept the six-cylinder 750 quite slim, and contributed towards its tidy-looking, purposeful appearance.

Stiff suspension, a strong chassis and the smooth motor meant that the 750 developed a reputation for being taut and responsive, although not massively fast.

The 900 was created by boring and stroking the motor to give 60mm by 53.4mm and thus 80bhp at 8400rpm. Three 24mm Dell’Orto carbs fed fuel to the 906cc, air-cooled engine which used two valves per cylinder.

Benelli tweaked the specification of the 900 to address some of the teething troubles encountered on the 750, and one of the benefits was a reduction in weight. The 900 weighed just 220kg dry – some 20kg less than Honda’s four cylinder CB900 which was current at the time.

The 900 also featured a fabulous Siltenium six-into-two exhaust system which resisted rot better than the straight six-into-six system fitted to the 750. Other novelties included the duplex final drive chain (now extremely expensive to replace, and owners recommended converting back to simplex chain – modern chains are more than up to the job of handling the power), cast alloy wheels and the moulded body panels which concealed the plastic petrol tank.

Removing the one-piece bodywork to access the tank area is one of those jobs which can cause grown men to weep quietly in corners.

Where the 900 excelled was with its braking, from triple Brembo discs featuring dual-piston calipers, and with its handling. The Sei’s firm rear damping made it feel much more European than the typically soft UJM ride, and meant that it was far easier to ride fast on smaller roads than most four-cylinder bikes on the market.

It was reasonably stable at high speeds and fitting modern shocks really helps – although the front end with its 35mm forks does seem somewhat skinny by today’s standards.

Even though the Sei was slower on paper than the six-cylinder competition from Honda and Kawasaki, in real life it could more than keep up with a CBX or Z1300 on A-roads.

Motor Cycle Weekly said that ‘its motor does not approach the technical excellence of several Japanese multis, but the Benelli’s handling, road holding and braking more than make up for its shortcomings.’

A 900 Sei would cruise happily at 70mph to 90mph, no problem. It covered a standing quarter mile in 13.3 seconds, with a terminal velocity of 99.8mph. In normal touring use the 900 Sei returned around 40mpg, although this could drop to 32 under extreme provocation. These days, most owners get around 48mpg, ‘dropping to about 43 if driven hard’ says Chris Grigson who edits the Benelli Club magazine. Roadtesters of the time reckoned that the 900 Sei ‘handles far better than Japanese multis, sticks to the road like flies to flypaper and can brake as if it has been run into a wall.’

However, there was an inevitable price premium for this interesting beast and Benelli customers paid a high price for unremarkable top speed and acceleration. 125mph was realistically the best you could expect from the 900, and it was mechanically noisy and somewhat ragged compared to Honda’s highly refined six-cylinder engine.

The Sei also suffered from some other typical Italian problems including an unreliable speedo, restricted foot space, weeping forks, slipping clutches and some oil seepage around the cylinder head. The bikes got better (and slightly faster) with later models, and the initially under-specified alternator was rapidly replaced.

The Sei is also often compared to Laverda’s triples but the two riding experiences are radically different. The Sei feels smoother and free-revving, lacking the low-down grunt of a Jota. The Benelli is lighter on its feet (and lighter overall) than the Laverda, but its engine feels more like a Japanese machine than a Continental one.

Less low-rev torque rewards riders who are happy to twist the grip – but fast lads should be warned; the Benelli doesn’t have a massive amount of ground clearance and sparks will fly on tight corners.

In total Benelli built some 3200 of the 750 version, but these weren’t sold in Britain – even so, there are more 750s than 900s in the owners’ club. The 900s can attract big bids at auction. In 2010 in the USA, one very low mileage 900 Sei sold for $18,000 while another, higher mileage example was up for grabs at $11,000.

They are more usually offered for sale on the European mainland and one started bidding in summer 2011 at $13,500 USD. A nearly-new 900 was offered for sale in Switzerland at the end of 2011 for £11,500.

However, reasonably-priced machines do come up for sale occasionally. A 1984 900 was sold in the UK at Bonhams auction in April 2011 for £5750. It had been recently restored and came with a current MoT plus an assortment of spares. So prices are comparable with Laverda 3Cs and the like – if you can make your purchase at the right moment.

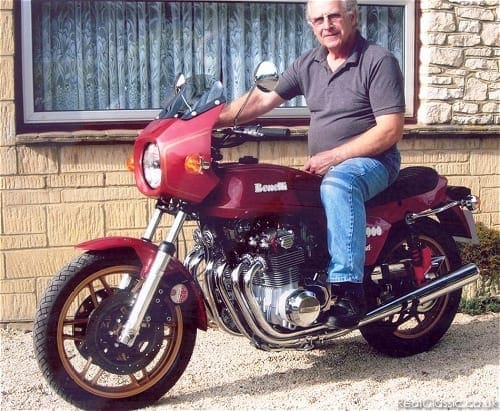

Some 2000 of the 900s were made until production ceased in 1985 – which happens to be when Phil Colin bought his own 900 for £600. It was five years old and had covered 18,000 miles. The Sei was ‘well used’ and ‘in need of a lot of work to make it nice’. So Phil set about him with the spanners and reconditioned or replaced ‘absolutely everything’ to do with the chassis.

This included ‘every bearing and seal’ plus powdercoating, rebuilding the forks and swinging arm, a complete new exhaust and stainless pipes, seat, wheels, cables, carbs, chain and sprockets – but not, you’ll be entertained to learn, anything at all in the engine department. The motor needed no work whatsoever!

As you can tell from its current condition, the Sei has been hardly used in the 25 years since it was reconditioned. In fact, it hadn’t run for so long that Phil couldn’t really remember what it sounded like. When he got it going again recently, he was startled to hear it.

‘The first time it started after 25 years – I had forgotten the sound! It’s amazingly smooth for an old motorcycle’. Now the Sei is used for occasional rides on sunny summer days. Phil fancies cleaning up the engine somewhat; ‘when I first bought it I couldn’t afford to have the engine castings blasted; soda-blast treatment would give them a super smooth finish.’ However, Phil’s not keen on modifying the Benelli; ‘I’m a bit of a purist and like the way it was made, although it would benefit from a modern ignition with more control over advance.’

Phil likes the Sei just the way it is. He reckons that if you’ve been tempted by the idea of a Sei then you shouldn’t pay too much attention to its detractors.

‘Just buy it and forget the critics and the pub experts. Just enjoy every minute!’