Only an expert or an optimist would attempt to rebuild a totally burned-out classic motorcycle. So here’s Frank Westworth’s guide to stripping down for idiots…

Every sane treatise on the subject of rebuilding motor vehicles insists that any successful restoration follows a few rules. This is in fact the case, and any sane person should ignore the way I do things because I am simply not entirely sensible when I rebuild bikes.

Sane authors (I was going to write; ‘sane experts’ but it occurred to me that I doubt any old bike experts are entirely free of a touch of lunacy) suggest that before you strip the bike down, you should photograph it in as much detail as possible. The idea is that if you can gaze upon smudgy photos of your project in its original cankered condition, then you will know where to replace the refurbished or new bits when reassembly time comes trotting unsteadily along.

This is a great theory, and I recommend it. In fact, I do it myself, displaying rare intelligence, and have never yet found the photos useful. The reason for this is consistent: Somehow I never photograph the bits which cause problems later. No idea why. Must have a loose nut somewhere.

You must also make copious lists, of course, but I never do that, because I would certainly lose the list. I would also inevitably write it in a sort of private shorthand, and then be completely incapable of deciphering it later when I commenced the listless rebuild process.

In the case of the seriously singed Toastmaster, I took loads of photos, not because I wanted to remember where things go (because I am a smartarse, and plainly know everything!) but to remind me of how appalling the wreck had been when I stood back and stared at the finally finished, shining and smooth-running masterpiece which would be the result of my fantastic skills. Yeah, right…

So as I stripped the ruin down, I took lots of pics. Real Mart may well have reproduced a few of them here. He may well have included the somehow spooky shots, like the handlebar switches which have no internals, but which are somehow still fixed firmly to the bars. Maybe he’s shown you the bizarre shot of the instrument panel, complete with crumbling steering damper knob, empty ammeter, baked bakelite light switch and the speedo, which was charred, and was in fact full of nothing but warped slag. Maybe there’s that poignant shot of the tax disc holder, complete with charred fragments of the last tax disc…

Tony Robinson’s tiresome Time Team never find anything this interesting.

Dismantling was not as easy as I’d hoped, either. Nuts were welded to bolts, steel washers were welded to anything cast, mazak items had vanished, as had everything combustible. Like all the grease in steering head and swinging arm bearings; like all the rubbers and seals anywhere there should have been rubbers and seals. The final drive chain was welded into an endless solid rusty link. The seat? Well, let’s not go there.

My favourite bit, though, was the superb black chrome effect on the silencers. Few Ariel twins had black chrome silencers as standard. And I am An Expert; I would know…

Like I said; dismantling was a complete pain in the posterior. I’d thought that the whole bike would obligingly fall apart under the gentlest of caresses with my favourite shiny Whitworths, but no. Although Sam the previous owner had sprayed sundry bits of the bike with a mysterious grey something, which meant that the rust was now in various fascinating – if unhelpful – patterns, bare metal-to-metal oxidation had taken a serious grip. This was not fun.

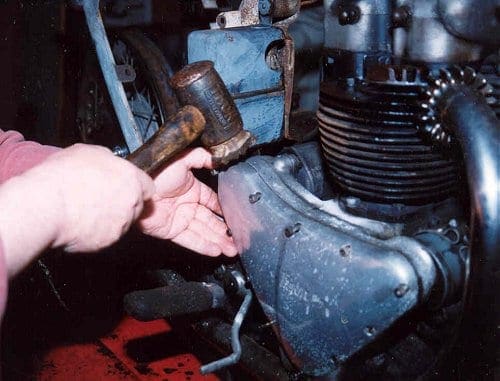

I had to resort to the liberal application of penetrating oils (Superslax, from a 5 litre can I’ve had since 1979, in memory of the Thatcher years), followed by a similarly liberal application of heat, more oil and a great big Thor hammer.

But despite heroic assaults with Thor, king of hammers, some things just would not dismantle. I could not, for example, extract the swinging arm from the frame. The rear hub had burned and melted so much that it was powdering under pressure, and the whole notionally QD rear wheel spindle assembly was welded solid. As were the rear wheel nuts, the brass ones, which were half melted and permanently welded to the steel studs in the hub.

Never, ever, buy a burned-out wreck. Never. Even if it’s free, it is too expensive!

But gradually, what had appeared to be a toasted, but fairly complete, motorcycle was disassembled, revealing that it was a pile of scrap, with very few re-useable components.

A little more bad news, then a little good!

One of the things I was pleased with was the state of the tinware. It was all there, and looked decently OK. Apart from the rear chaincase, which had been a glassfibre replica and had gone up in smoke. But… I dismounted the front mudguard, which looked cheerfully sound … and all the patches which had been brazed inside to fill the holes had been unbrazed by the heat of the fire and the thing fell to bits in my hands (officer!). That was a blow.

When I stripped out the rear guard … well, just like the front one, only a lot worse!

The oil filter (the one inside the oil tank) had melted, fallen inside the tank, and I have never been able to remove it, despite trying needle-nose pliers, hooks, magnets (the mesh is steel) and hours of hysterical yelling. Even the latter, generally so reliable a technique, failed. I now have four oil tanks, none of them the correct one. I am an expert on Ariel swinging arm oil tanks. Maybe RealClassicists would like a 45,000 word series on Ariel oil tanks? Or maybe you won’t…

And I am of course saving the best till last. This was a real surprise, too.

I took all the depressing pile of tinware over to Redditch Shotblasters so that they could work their messy magic and I could see The Whole Truth (or The Hole Truth, as it turned out). They could, Dave The Blast assured me, fix and powder coat almost anything. Except…

Well, the most amazing discovery was that the petrol tank, although it looked like a late Ariel tank, was in fact about ten percent bigger than usual, and a slightly odd shape, especially when compared to a normal item. Not only had the conflagration melted the braze of the tank’s seams, and burned out all the filler loading, it had exploded the petrol in a mild way, leaving all of the metal of the tank … stretched. Quite useless. I shall sell it at an autojumble some time in the future, baffling Ariel historians for the rest of time.

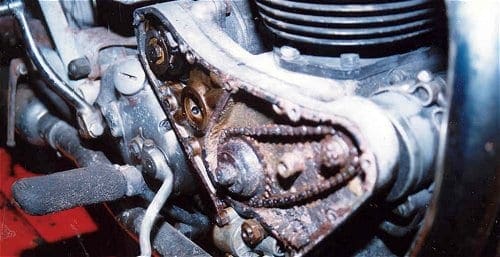

The good news, though, was that the engine was free, had very good, even compression, and turned over with no obvious mechanical traumas. It had, after all, been rebuilt for Sam the previous owner by Graham Horne, a good mate and serious Ariel expert, and it would have been gutting if that had needed another complete strip and rebuild. Likewise the gearbox.

It selected its gears, and although there was a mysterious slop in both clutch and gear levers, and although the gearbox oil had evaporated all its volatiles and turned into clingy treacle, it was free.

I heaved out the power train, filled everything with lots and lots of clean fresh thin machine oil and left it to soak. The next step was to start making lists of the parts I needed to buy. But that’s for next time: Autojumbling; An Idiot’s Guide…

Will it be finished before Frank moves shed again? Your guess is as good as anyone’s… Come back soon for the next episode!

———

*This feature originally appeared almost two decades ago. Scarily, at least one of the bikes mentioned in it still haunts The Big Shed!

Words and photos by Frank Westworth