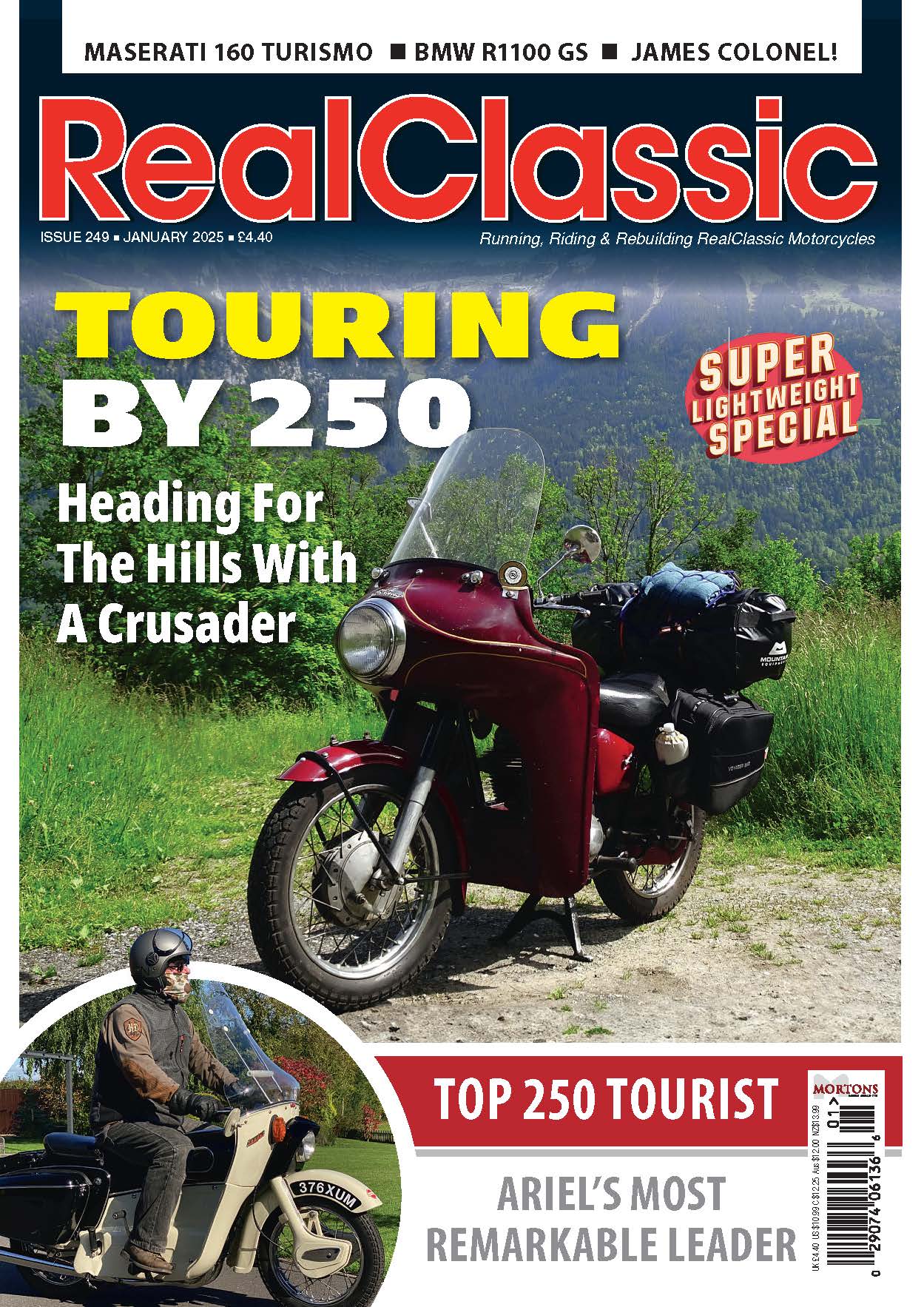

If you’ve revelled in the power and performance of a 750 triple, can you really be happy trading down to something smaller? Andy C shares his early impressions of a 1970’s 500 twin…

In life there are always milestones and turning points which you remember: your first day at school, your first love, your first bike. Some years back saw me arriving at one of those milestones when I bought a T160. I had longed for one ever since an old mate of mine had one when I was at college, and I rode a Triumph 750 Tiger.

After seven years of enjoyable (but at times frustrating and expensive) T160 ownership, I had to say goodbye – another milestone! Basically I had to reduce my outgoings, so I wanted a tax exempt, and smaller capacity / cheaper to insure bike. OK I have an RE Bullet as well, but I say that you always need at least two bikes!

With the money from the sale of the 160 burning a hole in my pocket, I started looking around for another classic bike. I had already decided that it would be a Triumph so that narrowed down the field quite a bit.

Sometimes when you see a bike, you get that feeling deep down which says that you simply MUST have it. That’s exactly what happened when I took the Daytona for a test ride.

It just looked, sounded and felt so right.

A mate of mine who has ridden a Daytona for years describes it as ‘the Triumph that everyone should own, and it’s true many people would like to own one, mainly because the motor produces far less vibes than the 650 or 750 twins, OK it doesn’t have the same grunt, but having said that a good one should be capable of pulling a genuine ton.’

|

|

500 Triumph stuff on eBay.co.uk |

When I test rode the Daytona, my mate’s voice echoed in my head. ‘A genuine ton’… well, I thought after warming it up for a few miles, let’s see what it will do. Off down the A303 around Wincanton, I really screwed it on in third and fourth, and without too much effort I saw the magic ton on the clock. Yes with a bit more effort it would probably have gone a bit faster, but – hey — I was only test riding the bike !

After returning to the vendor’s home with the bike still in one piece, and very little signs of any oil leaks, we haggled over the price, and agreed a figure.

So October the 11th 2004 saw me spending more money that I really wanted to on a 1971 Triumph Daytona, re-imported from Iowa back in 1991.

Riding it home on that sunny, chilly afternoon, there were two small but annoying problems that I would have to fix immediately. One was a backfire from the LH pot, the other was the notchy gearchange.

The backfire was cured easily by just removing the LH exhaust system and re-fitting it with the clamps, etc, in the right place. The gearchange was a little more difficult. Anyone who knows the 350 and 500 gearboxes will know how easy they are to work on, and the layout of the mechanism in the outer gearbox cover. Anyway, to cut a long story short, the incorrect springs were fitted, and the gear pedal shaft was sticky. Fixing this improved the action, but did not fully fix it. The gearbox still remains a little notchy, and I am convinced that I will need to pull the whole gearbox apart to fix it.

As I started to ride the bike, other small but niggling problems started to appear. Firstly the rocker caps kept unscrewing themselves, I did wire them, but the best fix was to fit some of the later inspection caps – these have O-rings instead of the fibre washers, and have not come loose to date. Secondly the plugs in the rocker boxes, for checking the valve clearances, leaked. This was because they had fibre washers and plumber’s tape on them instead of the correct copper washers (these washers are not flat, they are a special rolled profile – thanks Stuart of Stuart Motorcycles Highbridge for that info!).

I also carried out a service – just as well as three of the four valves had no clearance, and the timing was over advanced.

I whipped off the carbs to check for wear, correct jetting etc. Another good move, as the paper one of the gaskets on the manifold was overhanging into the inlet tract, and the right hand carb float had a slightly bent pivot pin, making the bike difficult to tickle. Jets, slides and needles all appeared to be correct according to the JR Nelson workshop manual that I bought. I say ‘correct’ but there appears to be umpteen variants on jet sizes / slides! All I can say is that after a decent run the plugs look a good colour, and the bike does not spit back when cold.

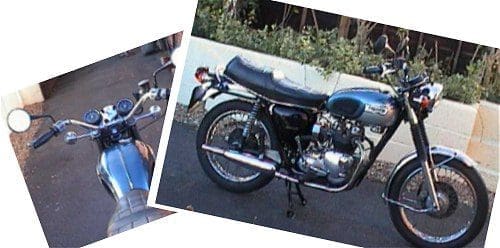

One thing that I have not mentioned yet and that is that the bike has a disc front end, sadly NOT genuine. I believe that only around 25 or so left the factory with a disc front end, and these were known as a T100D. Mine is a 1971 Daytona (the engine no indicates it is 1972 but apparently it was standard practice to build the engines in advance of the bike). The frame and engine numbers do match.

I once owned a 68 Bonnie that had the TLS front brake, and it has to be said that, from memory, the TLS brake was better than the disc, but I have yet to fettle the disc brake.

The bike looks like it has been very well cared for in its previous life. Virtually everything looks to be standard, even down to the plated nuts and bolts, although a few have been replaced with stainless. The tank has a nice patina – possibly original paint job — while the frame, tank and sidepanels have been powder-coated by the previous owner. I hope the oil tank was masked and or cleaned out internally afterwards!

The rear shocks are Hagons, and now I have set them for a firmer ride they seem to be OK. The front feels a little stiff, possibly because the front end has the heavier springs and dampers for a T150 — those were the forks used on the 25 or so ‘production’ T100Ds. The springs and dampers really need to be as fitted to the twins; remember that the weight of the Daytona is a good deal lighter than a T150. This is something that will be checked / fettled in due course.

So apart from the odd bits and pieces above, all I have done is tidied up some of the wiring – the last owner re wired it, but there were a few bits and pieces that I was not happy with. I also changed the oils and brake fluid.

So how does it ride?

It took some getting used to after the T160. It just doesn’t have the same grunt (not that you would expect it to). It starts first kick every time – even when people are around! — and ticks over just fine at a little over 1000rpm.

Clutch action is a little heavy; this may be due to the belt drive and clutch which the vendor told me have been fitted. I’ve not had it apart yet so I don’t know which sort of belt conversion it is, but it has yet to slip, and I have confirmed that there is a belt drive in the primary.

The Daytona’s light weight means that it can be flicked around with ease, and the braking (even without fettling the disc) is more than adequate. The handling improved when I fitted a new set of tyres as it had fairly shot Avons when I bought it – SM on the front and a Supreme on the rear, but it now has Metzelers.

Realistic cruising speed is around the 60 mark. At this speed the engine is turning around the 4500tpm mark, which does sound very busy. I am considering fitting a one-tooth larger gearbox sprocket which would reduce the revs at 60 by around 240rpm. Doesn’t sound a lot, but you try cruising at, say, 4000rpm and drop to 3750 – makes a hell of a difference. Some schools of thought say that fitting a one-tooth bigger sprocket ruins the performance, others say not. If I do it, then I’ll be the judge…

I must say that vibration is not really intrusive at all until you get to the 85 plus mark, and then it does start to buzz a bit. So unless you are going to go everywhere flat out, vibration should not be a problem. I would suggest that if you have a Daytona and you find it vibrates too much then you need to investigate why! Apparently these motors were designed and balanced to be revved.

Fuel consumption averages around the 45mpg mark – about the same as my old T160 did. It’s a little disappointing but, then again, the motor is working fairly hard compared to the 160. It uses hardly any oil, but there are a few minor weeps which need to be taken care of, and will be this coming winter.

Once you get used to revving the engine fairly hard, it has reasonably brisk acceleration, enough to annoy all but the determined (or more often than not suicidal) young baseball caped cage driver with large bore exhaust and 500Db audio system! It will pull a genuine (‘genuine’ according to the Smiths clock) ton, but I am happy bimbling around the countryside at 55 / 60 with occasional excursion up into the 80s – great fun.

At first I thought that I had made a big mistake buying it, but it grows on you. Compared to my 160 it’s throttle response is much quicker, and with the early ‘bottle’ style silencers it has a really cracking exhaust note. It doesn’t make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up like the 160 exhaust note, but does sound very business-like.

I no longer suffer the paranoia I had with the 160; the visions of terminal oil pressure demise (seems to be common among Tridents), and the mortgage-like costs to put it right, neither do I have to risk a hernia whenever I put it onto the centrestand – the Daytona is beautifully balanced. I miss the sheer power of the T160, but at least I have my memories!

If you want a bike capable of eating mile after mile of motorway, or you do a lot of two-up riding then this is not the bike for you, but if you are after a nimble, relatively cheap to run bike, that you will be using mainly on A- and B-roads, then consider the Daytona. But hurry — because apparently they are quite sought after.