Imagine a wormhole which sucked a 1930s classic bike forward to 2003 (and upgraded its electrics in the process). Steve The Toast investigates a tear in the fabric of time…

Brushes come in many sizes, and you can use one of almost any size to tar many different things. Today was a day for having a serious root around in my box of brushes. The brush I had intended to use to tar the CJ750 was just not going to work.

I arrived at Bowbury Engineering & Motor Works to test the CJ, fully expecting to be underwhelmed not only by its performance and build quality, but also by its character. After riding the bike, I realised that I’d made a fatal mistake – and my choice of brush AND tar was wholly inaccurate. It took little over an hour for me to fall hopelessly for the charms of the twin, which mesmerised me with almost every facet of its gentle nature. Here was a classic design, unspoiled by time and progress. Let me try to explain how it managed this incredible feat.

The bike is a present day, Chinese-built copy of a design that dates back to the pre-war BMW R71. It has a few modern-day refinements just to make life easier, but which aim to keep its original character intact.

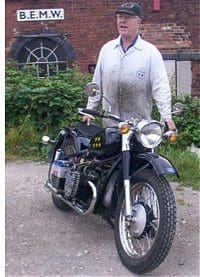

Meet John Lawes, the man behind the importation of this genuinely ubiquitous twin. John’s a man who is passionate about motorcycling to the extent of owning many old and rare bikes of East European manufacture as well as a healthy smattering of very unusual Brits. From a delightfully dusty, charismatic workshop in Derby he runs his import, spares and maintenance operation of this unusual breed. Walking in the door took me back 50 years, with old signs and postcards everywhere, and it leaves you with the certain impression that despite a general air of untidiness he can find anything he wants – it’ll be exactly where he left it last time.

The bike I was to ride was a solo, but you can have them in various configurations including an combination, with drive to the sidecar wheel giving you an off-road-ability as well as better cornering on tarmac. He wheeled out the bike for me, and after a bare minute of instruction on the various levers, pushed the electric start button. She rocked gently into life, settling into one of the slowest and steadiest tickovers I’ve ever heard, assisted, I understand, by a large flywheel. I can only describe the sound to you as a genteel ‘toof, toof’ from the fish-tail silencers.

‘Off you go then’ John cheerfully smiled, adding a casual warning that the seemingly small drum brakes ‘hadn’t settled in yet’. I smiled a knowing smile back at him, and stepped firmly on to the front of the gear-change rocker pedal to engage first.

As I pulled away across the rough, bumpy car park I was instantly impressed by the way the engine, with only 44 miles on its clock, pulled so smoothly from tickover. Once out onto smoother roads, I worked my way quickly through the box into fourth (top) gear and relaxed as the twin established its progress into an easy, long-legged lope. There is reverse gear too, which makes it even easier to maneuver if you have a chair on it.

I worked my way around Derby town center in the Saturday rush-hour traffic where the sheer rideability of this motorcycle came home to me. It only took me ten minutes to feel at home with its controls and low-speed handling. The CJ was easy to feed through traffic, it more than kept up with the ebb and flow, and handled in a very smooth and predictable manner. This one particular feature so impressed me that I found myself returning to the same large roundabout several times just to enjoy the positive feedback the bike gave as I swung it from side to side.

John had warned me that the gearbox was a little heavy and that ‘neutral could be tricky to find until the box beds in a bit’, which was correct, but it was at least a positive change and I got the gear each time. I only mucked up one search for neutral, as I sat at a set of traffic lights; predictably, by the time I had found it they had changed to green. The clutch is smooth and not at all snatchy, and correct, careful timing of your clutch / gearlever movement will reward you with smooth, quiet changes. Allied to the even, across-the-range delivery of torque, it makes for a relaxed ride which sums up the aspirations of the original 1930s blueprint.

The shaft-drive was reaction free as far as I could tell, I certainly felt nothing from it as I changed gear or swooped around bends. The bike tracks incredibly well, despite the aged-looking pattern of the tyres, and the very low center of gravity makes any weight disappear so it’s as easy to move around while parking as when riding. As to the brakes, they do indeed need time to settle in, and needed a firm hand and foot, but the bike encourages you to take an unhurried approach to your journey, which underlines the usefulness of the bike as a distance coverer.

All too soon my time was up, and I found myself back in his yard with an incredibly large smirk on my face. Here was a bike which had the look, style, performance and allure of a true classic bike of yore, but without the purchase cost or spares availability problems normally associated with running a 60-year-old bike, as well as being a great ride to boot.

All too soon my time was up, and I found myself back in his yard with an incredibly large smirk on my face. Here was a bike which had the look, style, performance and allure of a true classic bike of yore, but without the purchase cost or spares availability problems normally associated with running a 60-year-old bike, as well as being a great ride to boot.

If my ride uncovered any particularly annoying trait, I’m both surprised and delighted to report on how trivial it was. On hitting a very deeply recessed manhole cover, the main stand bounced down, hit the road, bounced up and down a couple of times more before settling back up. This happened a few times, and when I mentioned this to John he reported that they (the Chinese manufacturers) only fit one spring and it could probably do with two.

It was the only thing I could find to niggle about, it was pretty minor. I half expected him to say ‘try missing the potholes’, but he didn’t!

The bike comes with improvements to the electrical system, so over-engineered as to make ownership a breeze. You can also specify extras from an impressive list, not the usual silly chrome goodies, but sensible items. There are side-valve and over-head valve versions, left or right hand sidecars, of which the latter useful for military re-enactment groups or anyone who is a regular overseas tourer. Also, such things as higher gear ratios, a deep sump, sidestand, pillion seat, brake upgrades, as well as tool kits, can be ordered too. John will strip a CJ, repaint it, and make any modifications to it that you may want before you take delivery.

There are one or two things that an enthusiastic owner, and I think most will be, could do to improve the looks easily, including a battery cover and a bit of tidying up of cables and wires here and there, but we are talking purely about aesthetics here and not about practicality or reliability. The large battery is there to give you proper dependability. The smaller cell, which John says can be fitted above the shaft drive and under the frame rails below the seat, won’t give you 100% consistent starting on the frostier mornings, something that he feels is important. This truly is a bike for all seasons.

At what price does this archetypal motorcycling nirvana come, you may ask? Well, I think you could be in for a bit of a surprise in that respect. Prices for a basic side-valve solo start at around £2500. A sidecar on the left is just over £700, the other side £900. None of the other aforementioned improvements costs much, and for well under £3000 you could have a well-sorted solo on the road with great practicality and ruggedness, as well as having something that is a little bit more interesting than the mainstream of motorcycling. Insuring it will be refreshingly cheap as it’s in Group Seven and John has a deal worked out with a particular broker too.

Wherever John rides a CJ, it is mistaken for a true 30s machine that he has ‘done up’, and there are few visual cues to help people fathom out what it is or where it came from. He isn’t exactly sure how many CJs he has imported so far, but it’ll be into three figures soon. Depending on your requirements, it could take up to three months for your bike to arrive from the production line in the Far East as John orders small batches of them, usually around six at a time.

As you can see, the CJ features the sideways-on kickstart, and although it was easy to use, you’ll not need to. I also loved the little rubber boots over the top of the carbs! Seat suspension pre-load is adjustable to account for differing rider weights. You don’t get that on your Hayabusa!

John recommends running the engine, gearbox and final drive all on the same 40-weight oil, which makes it easier at service time. Because of the CJ’s simple design, anyone who has ever lifted a spanner could maintain their own pride and joy on a regular basis, and there is nothing on the bike which would require specialist tools in the normal run of things. He keeps most spares in stock and reckons there’s not much to go wrong with them anyway. The paintwork is a solid-looking black, and it has that heavily engineered feel of enduring quality of life for its parts.

For the last, I’d like to leave you with a quote from John’s BE-MW leaflet. I think it sums it all up rather well.

‘The CJ runs smoothly and effortlessly up to main cruising speeds. To get the best from the machine, change up early and change down late. The 1930s original did not need, or benefit from, high engine speeds, and neither does this 1990s version. Like the R71, the horse power is produced by horses with very thick, hairy, legs’.

People To Speak To

New “classics”? Better than old?