1950’s Britain was very different to today. So what was it like to run a classic bike then, a Triumph Thunderbird, when it was brand new? David Gambie remembers…

On reading the first issue of the RealClassic magazine, I was particularly taken with the article on the Thunderbird as it brought back many happy memories. I first saw the bike when it was introduced at the 1949 Show and decided that it could be categorised as a ‘must have’.

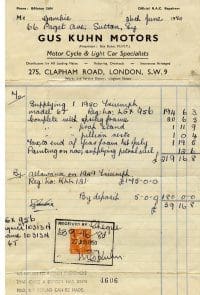

I placed my order on December 29th 1949 with Gus Kuhn who at that time ran an emporium in the Clapham Road, near the Oval. In those days Triumph were not off the shelf and I was not too disappointed to be quoted six months or so delivery time. I got the call in the last week of June and took delivery on the 1st of July.

I was part-exchanging my January 1949 Tiger 100 on which I had done 16,840 trouble-free miles and so was totally familiar with most aspects of the Thunderbird. Gus gave me a hard time in the haggling but I was content with the deal. He had a raging cold, which he attributed to the fact that his Austin A40 Devon Saloon had a heater and he was missing out on the fresh air. I would have pointed out that the windows wound down but felt that that sort of remark could adversely affect the deal, so stayed shtumm.

I persuaded them to put another quart of petrol in the tank, completed the administrative aspect and then I cast my leg over for the first experience of 34bhp. All the Triumphs I’ve owned have been easy starters and this one was no exception. First prod and she was away, quieter than the T100, but then, so much younger. The power characteristics were different, unsurprisingly, and I was quite pleased at the level of urge exhibited so far down the rev scale.

The much-vaunted improved gearbox was as slow changing in the lower gears as the T100 had been and the clutch appreciably heavier in operation but not onerously so. In all, I made my way home well pleased with my latest acquisition.

It being summer I thought an evening’s running-in was a must. Toddle out to Dorking, down to Littlehampton, coast road to Brighton, back up the London Road, beddy-byes by eleven.

I did six miles – as I turned on to Headley Common the back end stepped out in the most violent way and I almost lost it. I had picked up a brand new, recently galvanised 6-inch nail, which had ruined my brand new rear Dunlop Universal. Amazingly, it hadn’t passed between the blocks of the tread, but right, plumb dead centre of a block.

We didn’t have mobile phones, but we did have AA boxes and on the end of the phone within was a very nice man with a shiny yellow Beesa M20 and box sidecar, containing all the kit necessary to get me back on the road. It took a couple of hours and we both enjoyed repairing the tube on the grass and yacking motorcycles. As he said, it was a real pleasure to work on a bike and not get your hands dirty. It was with the greatest reluctance that he was finally persuaded to accept a ten-bob tip. He left urging me to get a new tyre and tube on the morrow. I had every intention of so doing but never did and I covered 10,000 plus miles on his patch. Death where is thy sting?

At that period in my life I was covering 1000 miles plus a month so it wasn’t long before I worked the bike up to 80mph, at which point I discovered the claim of ‘500 miles at 90mph with a final lap at 100mph around Montlhery with a perfectly standard machine’ was a con.

My Thunderbird wouldn’t even sustain 80mph. It was obviously suffering fuel starvation and in some dudgeon I phoned the factory to be told ‘Oh yes we know all about that, what you need is blah, blah, blah which will only cost you a fiver or so at any Triumph agent.’

We now have laws to protect us of course, but I found it disquieting and it considerably influenced my view of ET and his empire. With the mods fitted, which comprised two new taps and attendant connector piping to the carburettor, the bike now flew. An indicated 100mph, probably a genuine 90 but fast enough for me, came up regularly.

Came the wet weather and the bike’s Achilles’ heel was revealed. After an hour or so the front brake went, another hour and the rear was on sympathy walk out. You don’t just find this out — you DISCOVER it in the biggest way possible, like when you really do need to lose some speed. Anyone not having experienced this first hand will not have a clue what I’m talking about but your brain, having registered that your right-hand is clamping the lever up to the bars, dials in deceleration to the rest of the body – when it doesn’t get it, it says ‘you’re still accelerating’. The body then responds with ‘I think a quart of adrenaline would be a good idea’ and injects same.

It’s at this point that the power of prayer is demonstrated, or not. Either way, it will be some time before the spasms subside.

For me once is enough. I’m what is called a fast learner. From then on in, after half and hour continuous wet, it was two fingers on the front brake and the ball of the foot lightly resting on the back pedal. No more problem with brakes I was still on the same linings when I sold the bike at 13,000 miles, whatever that tells us.

I thought then, and still do, that for covering distances in comfort with reasonable economy and quite highish average speed it was the best bike on the market despite these little foibles.

A frequent run of mine, which I did throughout the year, from my home in Surrey to the village of Cogenhoe in Northampton, a distance of 108 miles, was regularly achieved in an hour and three quarters at 62mpg. To put that in perspective, if you’ve got a 1950 road map have a look at it.

It was whilst doing that particular journey that another little character-forming quirk was revealed. I had deviated to Chalfont St Peter to pick up a friend and transport him to Northants. I was on slightly unfamiliar roads so was being reasonably circumspect with the speed. Above Whipsnade Zoo we happened on a left hand, slightly uphill sweep, quite open with plenty of visibility so I left the speed on, I would guess about 75ish, and heeled into the bend.

The handlebar then took on a sort of left-hand rotary motion and simultaneously the bike started to move out. It was my first ever experience of the Triumph weave and I found it most interesting, while at no time feeling threatened by it. I subsequently tried to reproduce it to see if I could analyse what was going on but it never happened again. Looking back I think that the weight of the suitcase that my pillion had roped to his back could have been an influence.

The handlebar then took on a sort of left-hand rotary motion and simultaneously the bike started to move out. It was my first ever experience of the Triumph weave and I found it most interesting, while at no time feeling threatened by it. I subsequently tried to reproduce it to see if I could analyse what was going on but it never happened again. Looking back I think that the weight of the suitcase that my pillion had roped to his back could have been an influence.

During the winter of 50/51 I was riding back from Salisbury and, running late, had been stoking it up. As I came across the Hogs Back in the darkness of a January night I noticed I seemed to be going an awful lot faster than anybody else. On the Guildford by-pass it all went kinda light and I realised we were on ice so I backed off to the ‘I can now fall of comfortably’ speed.

Then I became aware of a squealing noise emanating from the front hub area. Stop, front stand down, spin wheel – diagnosis dry bearing. With fifteen miles to go it was press on time. When I checked the bearings they were bone dry but I repacked them and they saw out my time with the bike.

The Thunderbird continued to turn in absolutely reliable service. I have always been most meticulous with maintenance and oil changing and I’m sure it pays.

I had discovered a source of pure benzole, actually it was the same source as my black market petrol, and I found that by mixing it 50/50 the dreaded pinking was totally eliminated, the only downside was that it seemed to accelerate the coking process. The other downside was that of course it only worked on the outward journey, so if you were going to show Matey Boy on his Vincent the way, it had to be on the first tankful as you wouldn’t hold him on straight 72-octane if he was any good.

Harveys, a Triumph agent over in Victoria somewhere, was advertising inlet manifolds with highly polished bores on an exchange basis. Although I was well capable of reasoning that their advantage would not be measurable I nonetheless had to have one. I motored over to Victoria and in the roadway outside stripped off the manifold and walked into the shop.

As I waited my turn for service I became aware of considerable agitation amongst the staff behind the counter. They were all sniffing the air wildly and getting very round-eyed. It wasn’t until I heard one of them asking of us on the other side of the counter whether we could smell gas, by which time all cigarettes had been extinguished and people urged not to touch light switches, that the penny dropped and I realised that it was me, or rather my benzole-soaked manifold and fingers. I fessed up – but I thought that they might have been a little more gracious in their acceptance of my apology.

My time with the Thunderbird was running out, although I was unaware of it.

We used to spend a few Sundays on the beach down at Clymping in Sussex. It was mid-August in 1951, the Thunderbird just over a year old, it had nearly 13,000 miles on the clock but was absolutely immaculate. I thought I loved it.

As I motored across the stubble of a recently harvested field my rear wheel dropped into a rut. A guy and his wife walking to the beach stepped across to give me a hand, he grabbed the left-hand rear mudguard stay and hefted the Triumph out of the rut. As I turned to thank him I saw him looking at his hand which was covered in black graphite grease thrown off by the recently lubricated chain. I was mortified.

On Monday I stopped at Gus Kuhn’s establishment and did a deal on a shaft-drive twin, but that’s another story, as they are wont to say.

Similar tale to tell?