Is this any way to restore a traditional British classic bike? The story of Frank Westworth’s improbable rebuild continues. Slowly…

‘That’s an Ariel Huntmaster, that is.’

‘What is? That pile of bits?’

‘What pile of bits? That’s an Ariel Huntmaster, that is…’

My first Ariel, my first Huntmaster, was not in fact mine. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t ride it a lot, nor that I didn’t love it like a brother, because I did. It actually belonged to my mate Geoffrey, who both bought it and, later, destroyed it several times.

No, while Geoffrey had his first Ariel, I had my first Matchless, a 1961 G12. We rode together a lot, often up and down to London town from our Somerset homes, back when the M4 was just a stumpy wee thing; we rode the A361 – A4 route, which was busy, fast and fun.

Geoffrey and I ribbed each other about our bikes, as youths are wont to do. There was nothing in the performance (although Geoffrey entirely understood the purpose of the twistgrip and was perfectly capable of fixing all the faults which 100percent use of that twistgrip produced: I didn’t, and wasn’t), and there was nothing in the handling (Geoffrey entirely understood that when the rests were worn down to the metal and were grinding away, you should twist that grip further and lean off the inside of the bike: I felt pain on his behalf).

The comparison which provided most hours of harmless, intoxicated debate was between the two electrical systems. The Ariel boasted old-fashioned dynamo lights and magneto sparks; the Matchless, modern alternator and coil. I could ride after dark for more than the half-hour or so that his Ariel’s battery could power his lights. I won.

Until the Matchless’s primary chain cut through the alternator lead…

As you can see, I have long had a thing for Ariel’s stylish 650.

As you can see, I have long had a thing for Ariel’s stylish 650.

Memories like these provide encouragement when dark days are all around. Days when nothing will fit. Days when simple tasks are proving entirely impossible. Days when Dame Logic and Sister Commonsense chorus that ‘If you want a Huntmaster, then buy one which works, dummy!’

Once you have entirely disassembled your project bike, surely the good bit is next? This is surely the time for the fun and frolics of reassembly? There I was, surrounded by piles of painstakingly cleaned, carefully assessed and reluctantly scrapped original bits, along with a smaller but much more impressive pile of shiny new bits, while attempting to take comfort in a cosmic wossname kind of way from the glittering fact that I now had no money left to spend, and therefore need not worry about how I should spend it. Dark days, like I say.

Then the phone rang. It was Sean Hawker, stout electrical superhero from CMES. I would certainly believe you if you told me that the character of Magneto from the X-Men comic-strip and movies, was modelled upon Sean. He has this amazing, superhuman magnetic effect on the contents of my wallet!

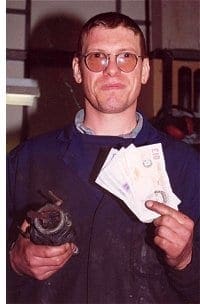

Sean rang to tell me that the magneto and dynamo from the Toastmaster were fixed, and I could collect them whenever I liked. I was staggered. How on earth had he fixed them? I mean, there is a limit to what you can do with a handful of semi-melted metallic slag, even if you are a superhero. But no, he assured me, fixed they were.

‘How much?’ I asked. ‘How big is the damage?’

He named a price.

I went pale (hard to do over the telephone, but always a good bargaining ploy. In fact the price was a lot less than I’d feared). We agreed to meet at a show. He would give me spangly new electrical gubbins; I would give him a Famous Westworth Cheque (good for framing to show visitors, but for little else).

I sat in The Shed and gazed ever harder at the wreckage.

I drank bad coffee, smoked virtual Woodbines, conversed with guardian angels in my search for The Way Forward. Ages passed, continents shifted, entire civilisations rose and fell, suns burned out and cooled, and still I could see no Way Forward.

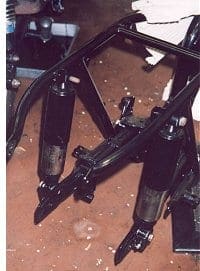

Then I thought ‘Stuff this!’, tipped my shiny repainted frame onto its side and fitted the centrestand. That scratched the shiny new powdercoat, broke two of my guitar-picking fingernails, and unleashed a torrent of energy! Hurrah. We’re moving again.

Once the centrestand is fitted the bike sits at balance on front wheel and stand, and becomes loads easier to work on. Fitting the centrestand is of course a complete nightmare if you’re not an Ariel expert (I wasn’t) but that nightmare can be readily overcome if you have both big hammer and a profound understanding of obscene vocabularies (I do).

Have you ever fitted one of these stands? If you ever feel that Real Life Is Passing You By, or that Everything Is Just Too Easy, then whip the engine plates out of your Ariel, remove its centrestand, and then refit it.

You have to remove the engine plates (and the engine, of course!) otherwise the frame rails won’t move apart. If they don’t move apart, refitting the centrestand is too easy.

Happily, my frame’s lower rails had eased apart while it was being blasted and refinished, and my centrestand’s two lugs had mysteriously gone out of alignment. This meant that the two pins upon which the stand pivots, and which are retained by four (count them!) fiddly circlips, could not be aligned by anyone whose physical strength was less than Superman’s.

Superdooperman also needed three arms and at least one eye on a stalk.

I had Thor, King of Hammers. It was lonely in The Shed, and it was a long, hard winter…

Words and photos by Frank Westworth