At this time of year, all eyes are on the Isle of Man TT races when man and motorcycle take on the most challenging race track in the world. Just how do you hone your skills to tackle the 37 miles of the Mountain Circuit? Well, you practice, of course…

For some it will be a fading memory and for others it is an aspect of the Isle of Man TT known only from hearsay, but 2018 sees the fifteenth anniversary of the last early morning practice sessions at the TT and MGP.

Loved by some, disliked and even loathed by others, morning practice was part of the Tourist Trophy races right from their outset in 1907. Indeed, dawn outings were the only ones available to riders up until 1937 when the first evening practice was held. In the earliest days, practice extended over two weeks. Yes, that meant two weeks of very early rising if you were a marshal. The unwelcome aspect of such an early start was made worse by the fact that, whereas in later years riders were despatched at 5.15am, during the early decades the first man was on his way at 4.30am.

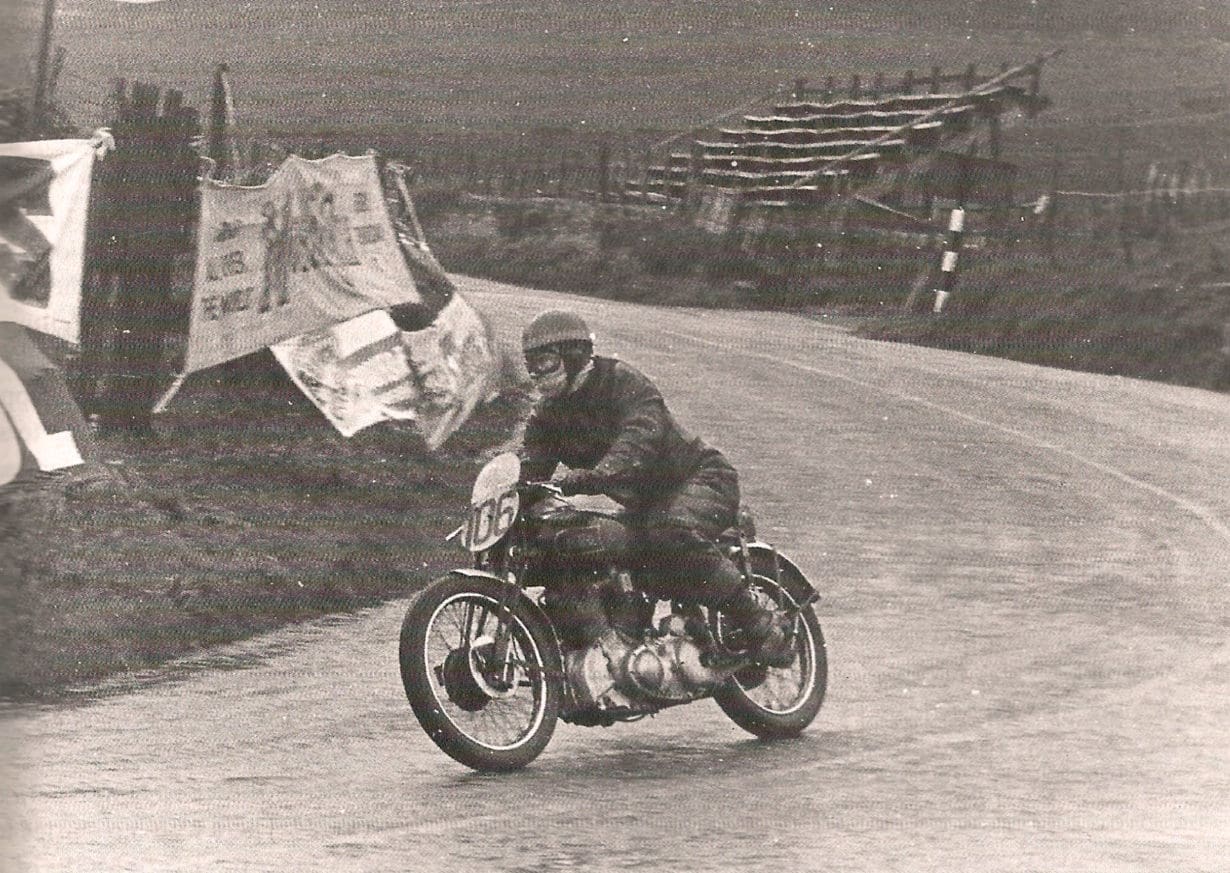

A cautious G Clark rounds a spectator-free Creg ny Baa aboard a Vincent, during a wet early morning practice session for the 1953 Clubman’s TT

In those early years, Douglas was the centre of TT activity but not all the early race teams stayed there, with Triumph and Levis taking accommodation in Peel and Scott choosing Ramsey. For their convenience, riders were permitted to join practice sessions at Ballacraine and Ramsey. However, it was not only riders who could join at such spots, because before 1928 the roads of the TT course were not closed to ordinary traffic during practice.

It is difficult to imagine, but horse-drawn carts, lumbering lorries, cyclists, etc, could use the roads to go about their normal business. It was a recipe for disaster and in 1927 Archie Birkin was killed when he swerved to avoid a fish-van and crashed, just outside Kirk Michael, at the spot that now carries his name.

Thereafter, the Road Closing Orders which reserved the exclusive use of the roads for competitors during racing, were extended to cover practice periods. From 1928 the roads were closed by the passage of an official car. A report from 1936 – by which time practice had been reduced to nine morning sessions – told that Jack Williams was first in the queue of starters. When the course car arrived back at the Grandstand, Jack was told: ‘good visibility, lots of wind and millions of rabbits’. As first man and unpaid rabbit-scarer, he left at 4.33am.

Local hotels made special arrangements to cater for such early risers. The popular ‘Falcon Cliff’ in Douglas adverted ‘guaranteed practice calls at 3.45 am with refreshments.’

Such early morning proceedings were wearying, not only for those connected with the racing, but also for local inhabitants. Few riders had vans in those days and sleep would be shattered by the sound of racing bikes being ridden to the start. Indeed, the noise in some of the enclosed back-alleys of Douglas must have been like the worst thunderstorm, as riders bump-started and blipped their bikes in the early dawn.

Then, for the many people living within earshot around the 37-mile course, something like a Manx Norton going past at full-bore was guaranteed to provide an unwanted wake-up call.

Early morning rising was a requirement for all involved: riders, marshals, officials and spectators. Not everyone found it easy and Travelling Marshal of the early 1950s, Len Parry, took unusual precautions to ensure that he woke on time. Upon retiring to bed at Mrs Cringle’s Studley House establishment on Douglas Promenade, Len would tie a piece of string around his foot and lower the other end out of his front bedroom window. Fellow Travelling Marshal and guaranteed early riser, Fred Hawken, would give the string a tug as he passed on the way to where he garaged his bike.

Legend says that, in later years, a few riders, some star names amongst them, would finish a night on the town at the casino and go straight from there to ride in morning practice…

In their last years of early morning use, roads were closed at 5am by virtue of the official Road Closing Orders and the first rider was despatched at 5.15am – slightly later at the MGP. Being up so early presented an unfamiliar world to many, but even experienced riders were shocked when they read the information board displayed before one morning practice at the MGP. It told them that conditions were generally good ‘except for frost here and there.’

After the introduction of the first evening practice in 1937, these sessions gradually increased in number and morning ones reduced. Strangely, some riders vied for the ‘honour’ of being first away in morning practice, and amongst the most successful in immediate pre- and post-war years was privateer Les Higgins.

It was Les who was first on the line with his Velocette on the morning of Monday 29th May 1947, for what was the first post-war TT. It was a nostalgic moment for him and for some of those watching, because he had been first man away in practice for the last TT meeting before war broke-out in 1939, eight years earlier.

Nowadays, the first practice session is held on a Saturday evening, but for many post-war years it was on Monday morning. Everyone went out together in those days, so newcomers and old hands would be up at an early hour, climbing into cold, stiff leathers and heading for the start in the near dark. After the bustle of scrutineering and in the chill of a just-breaking dawn, they were despatched on their high-speed laps.

Hardy spectators would also be out, for they could easily find themselves an empty viewing spot, sit listening in the silence of the Manx countryside and then, faintly, pick up the distant sound of a racing motorcycle. It was an experience unique to the Isle of Man. The sound would come ever closer, until machine and rider leapt into view followed by many others; for practice could be much busier than a race.

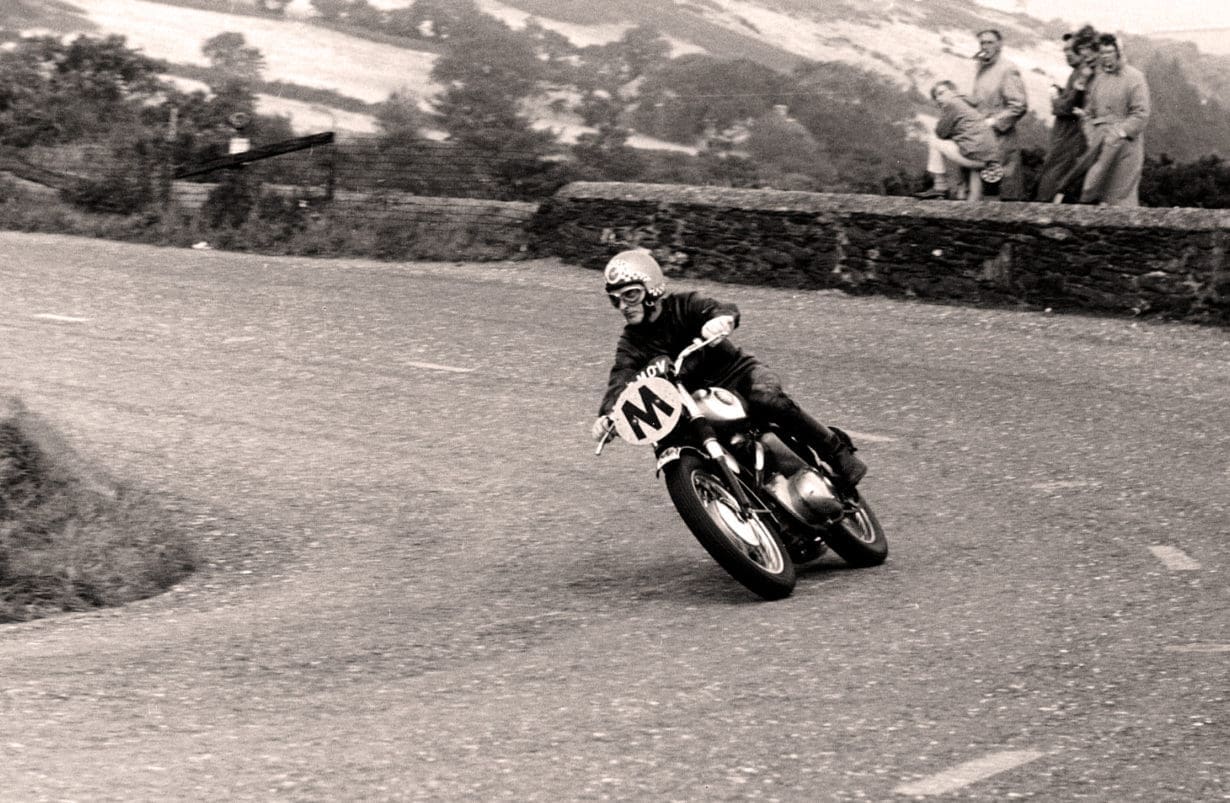

Travelling Marshal ‘Kipper’ Killip rounds the Gooseneck, in front of a few hardy early-morning spectators

In their last few years of use, morning sessions were reduced to three (Monday, Wednesday and Friday) with the option to include Saturday if necessary, and then to just Monday and Wednesday, with Friday in reserve. They remained unpopular with some riders, a few of whom always gave them a miss, with even more doing so if a look through the bedroom curtains at 4.30 am showed it to be wet.

However, most recognised that they still offered track time, to aid course-learning and machine set-up, so half-asleep riders, mechanics and helpers would make their way to the start area at the grandstand. As ever, marshals and officials could not pick and choose, for they had to be on station whatever the weather!

Come 2004 and morning practice no longer featured at the TT and MGP, although the organisers had a couple of emergency sessions reserved in case they lost any evening ones. Mixed reasons were given for dropping the morning times. These included claimed difficulty in getting sufficient marshals, together with pointing of fingers at ever increasingly specialised tyres that were said to be unsuitable for the mixed road conditions which could be found at such early hours.

Attempting to compensate for the time lost by the dropping of morning practice, evening sessions were extended slightly into the gathering dusk and practice opportunities were provided after race-days. That is the situation which prevails today.

The topic of morning practice divided opinion amongst the racing fraternity, for almost the hundred years in which it was used. Now it is just a memory and a part of Island racing that has gone for ever.

———-

Words and photos by David Wright