Scott’s innovative engineering set the standard for two-strokes for decades. These idiosyncratic machines inspire dedication and exasperation in roughly equal measure in their owners – but they’re capable of travelling very high mileages and still abound on the classic scenes, as Richard Jones discovers…

I’ve never liked squirrels; rats cunningly disguising themselves with furry tails and nasty, beady little eyes that follow you everywhere. Flying squirrels would be even more repellent – imagine those little blighters heading towards you at eye level. Given this dislike, it is curious that I am fond of Alfred Angas Scott’s eponymous motorcycles – although if you have seen one swooping up Sunrising Hill at full chat on the Banbury Run then you may have some sympathy with me.

Scott was drawn to two-strokes in around 1901, when he is said to have fitted an engine of his own design into a Premier bicycle which powered the machine via friction rollers on the front wheel. It was, according to Cyril Ayton, ‘almost certainly the first vertical twin engine of any consequence.’

Scott was drawn to two-strokes in around 1901, when he is said to have fitted an engine of his own design into a Premier bicycle which powered the machine via friction rollers on the front wheel. It was, according to Cyril Ayton, ‘almost certainly the first vertical twin engine of any consequence.’

By 1908 the engine was a 333cc unit with the cylinders cooled by air flow but with water cooling to the heads. By 1911 the engine had increased to 486cc and was fully water-cooled. Induction was controlled by a rotary valve and manufacture was undertaken at Scott’s own works in Shipley.

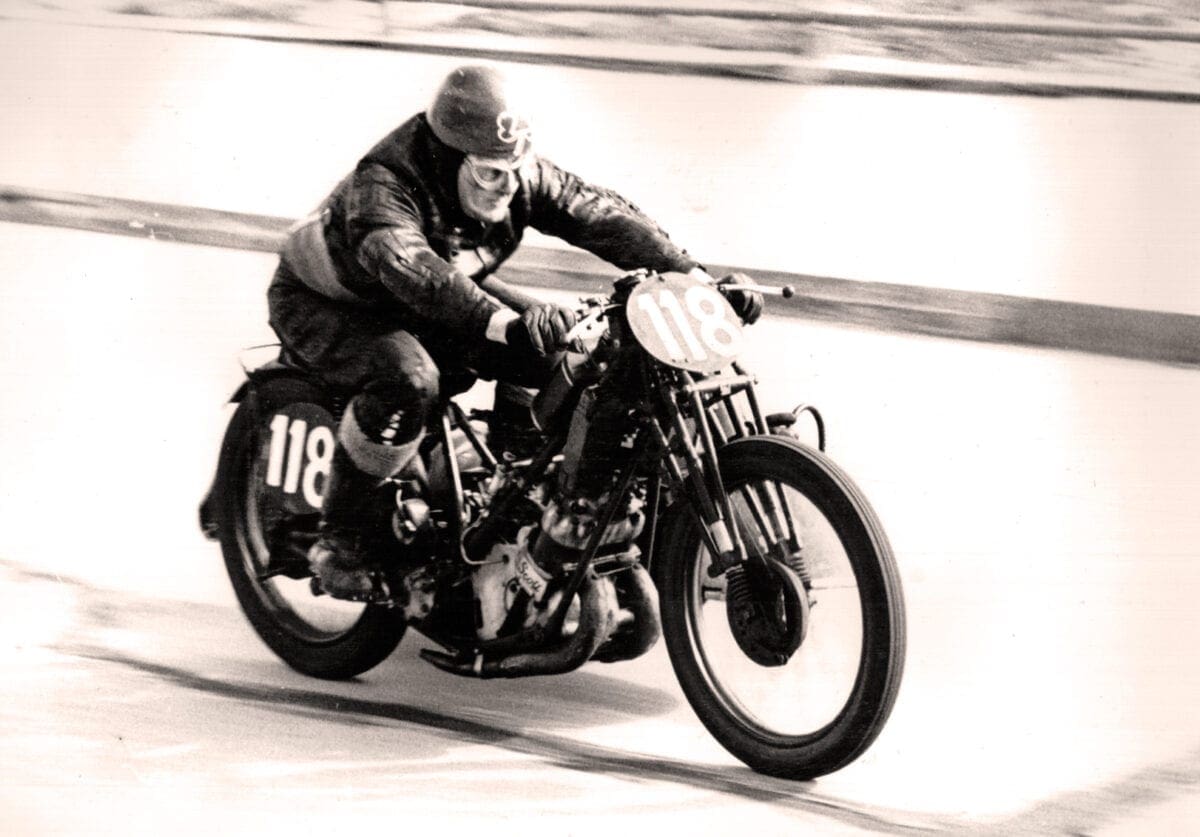

A 596cc Scott and sidecar in action at the Ramsgate sprint in 1963

A 596cc Scott and sidecar in action at the Ramsgate sprint in 1963

The following year a Scott won the Senior race at the TT and set the fastest lap, winning again in 1913. Further innovations followed with the first 489cc, two-speed Squirrel appearing in 1922, and the Flying Squirrels appearing four years later. ‘Scott produced some of the most distinctive and esteemed motorcycles of the age,’ says Cyril Ayton.

The bikes certainly could be durable in use – the VMCC’s founder Titch Allen owned a high-comp 600 which had covered more than 200,000 miles in its early life. ‘Scotts have a reputation of longevity,’ he explained. ‘The smooth torque of a twin-cylinder two-stroke is easy on the moving parts. Water cooling prevents extremes of temperature which often shorten the life of air-cooled four-stroke cylinders and valves. They were made of best-quality materials without penny-pinching economics.’

Yet the bikes could be far from straightforward to keep in good order. Titch said he ‘coaxed and cursed Scotts, loved and hated them (often on the same day) and yet had never been able to divorce myself from them completely.’ His Flying Squirrel would reach 75mph ‘when it’s in a good mood,’ and only with its preferred magneto fitted. ‘This Scott is very fussy about magnetos. The only one it likes and behaves properly with is a little old BT-H. With the original-equipment Lucas magdyno it sulks, loses its willingness to rev and develops an asthmatic cough.’

Yet the bikes could be far from straightforward to keep in good order. Titch said he ‘coaxed and cursed Scotts, loved and hated them (often on the same day) and yet had never been able to divorce myself from them completely.’ His Flying Squirrel would reach 75mph ‘when it’s in a good mood,’ and only with its preferred magneto fitted. ‘This Scott is very fussy about magnetos. The only one it likes and behaves properly with is a little old BT-H. With the original-equipment Lucas magdyno it sulks, loses its willingness to rev and develops an asthmatic cough.’

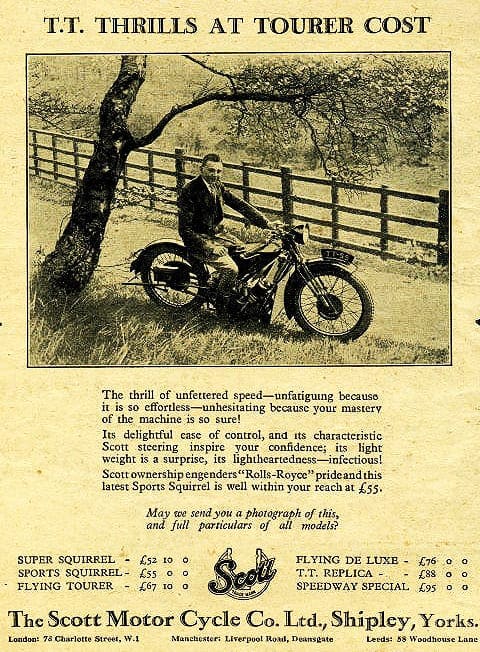

Scott of Shipley were certainly proud of their product, selling its ‘silence, speed, service, smoothness and simplicity.’ Unlike many motorcycles of the era it was ‘made throughout in the Scott factory, ensuring uniform quality and workmanship.’ They weren’t shy about making big claims for their product: ‘The Scott gearbox is the strongest in the industry. The Scott frame is the strongest ever made. Scott road-holding and cornering are proverbial. The Scott twin-cylinder engine has fewer moving parts than any other motorcycle engine of similar capacity.’

Scott of Shipley were certainly proud of their product, selling its ‘silence, speed, service, smoothness and simplicity.’ Unlike many motorcycles of the era it was ‘made throughout in the Scott factory, ensuring uniform quality and workmanship.’ They weren’t shy about making big claims for their product: ‘The Scott gearbox is the strongest in the industry. The Scott frame is the strongest ever made. Scott road-holding and cornering are proverbial. The Scott twin-cylinder engine has fewer moving parts than any other motorcycle engine of similar capacity.’

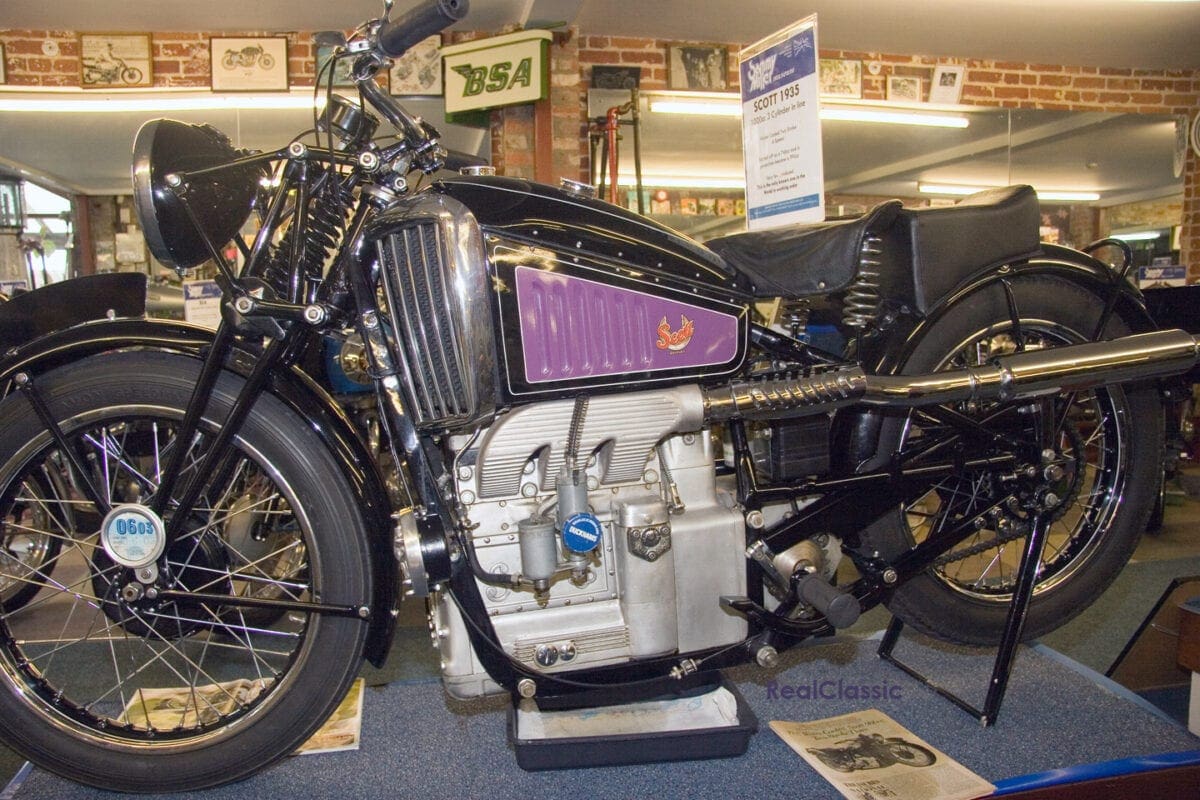

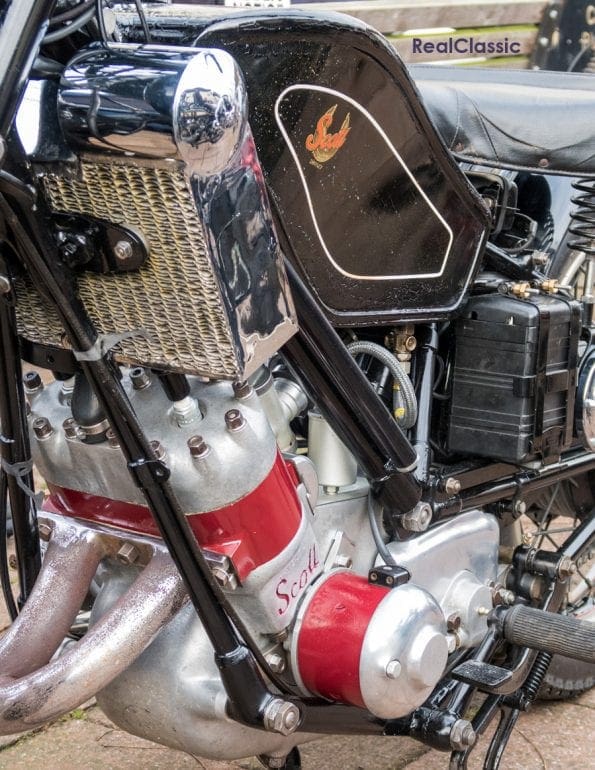

Scott’s four-speed three-cylinder 1000cc two-stroke of 1935

Scott’s four-speed three-cylinder 1000cc two-stroke of 1935

Further innovation was needed to keep things on the boil but Scott died in 1923. Thereafter, an inline three-cylinder machine appeared in the mid-1930s, of which few were built. By 1928, the three-speed 498cc Scott cost £93 – when a four-speed four-stroke Rudge 500 was just £46. Voluntary liquidation led to Scott being sold and relocated to Birmingham after WW2. Production of bespoke bikes to customer order continued, inspiring George Silk’s Special of the 1970s.

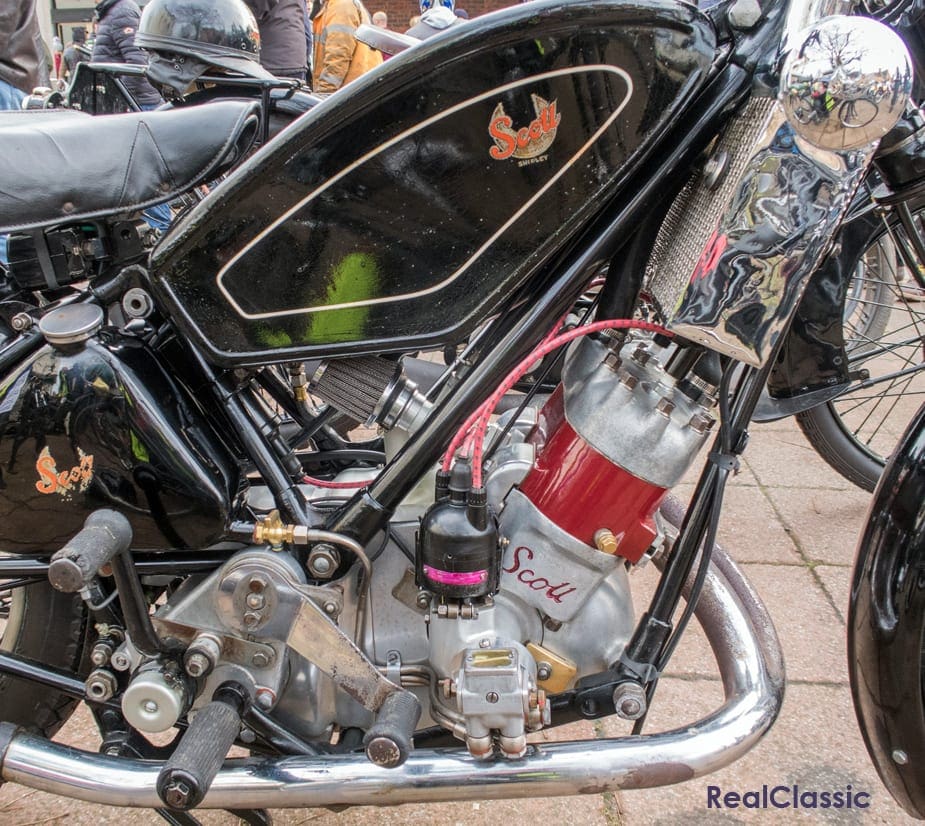

This example was ridden to the Classic Stony gathering on New Year’s Day and dates from 1949. It is, I believe, a 596cc Flying Squirrel with a rigid rear end and Dowty telescopic forks at the front, a dual front brake and full width rear brake, a roll-on centrestand and coil ignition with a distributor on the right. It’s a handsome machine which deserved a much better future than it received. It took another 30 years for Yamaha to introduce it’s water-cooled two-stroke range with much success; more investment and foresight could have seen Scott beat them to it and still be around today… but such is life. I blame the squirrels.

This example was ridden to the Classic Stony gathering on New Year’s Day and dates from 1949. It is, I believe, a 596cc Flying Squirrel with a rigid rear end and Dowty telescopic forks at the front, a dual front brake and full width rear brake, a roll-on centrestand and coil ignition with a distributor on the right. It’s a handsome machine which deserved a much better future than it received. It took another 30 years for Yamaha to introduce it’s water-cooled two-stroke range with much success; more investment and foresight could have seen Scott beat them to it and still be around today… but such is life. I blame the squirrels.

——–

Words and photos by Richard Jones

Richard maintains and adds to a simply gigantic online archive of vintage vehicle photos: visitors are welcome to drop by and admire other classic bikes he’s discovered on his travels

If you missed Vintage Stony then make sure you get to Classic Stony, usually held in early June