In 1968 Soichiro Honda rode his firm’s 10 millionth motorcycle off the production line. That bike was the ground-breaking CB450 Black Bomber – notable not least for its use of novel valvegear with torsion-bars ‘springs’ in its top end. It wasn’t long before racers transformed the CB streetbike into a world class competitor, and the Drixton Honda was born. They’re still campaigned to great success in classic series – and make the basis of a truly cool café racer, as seen here…

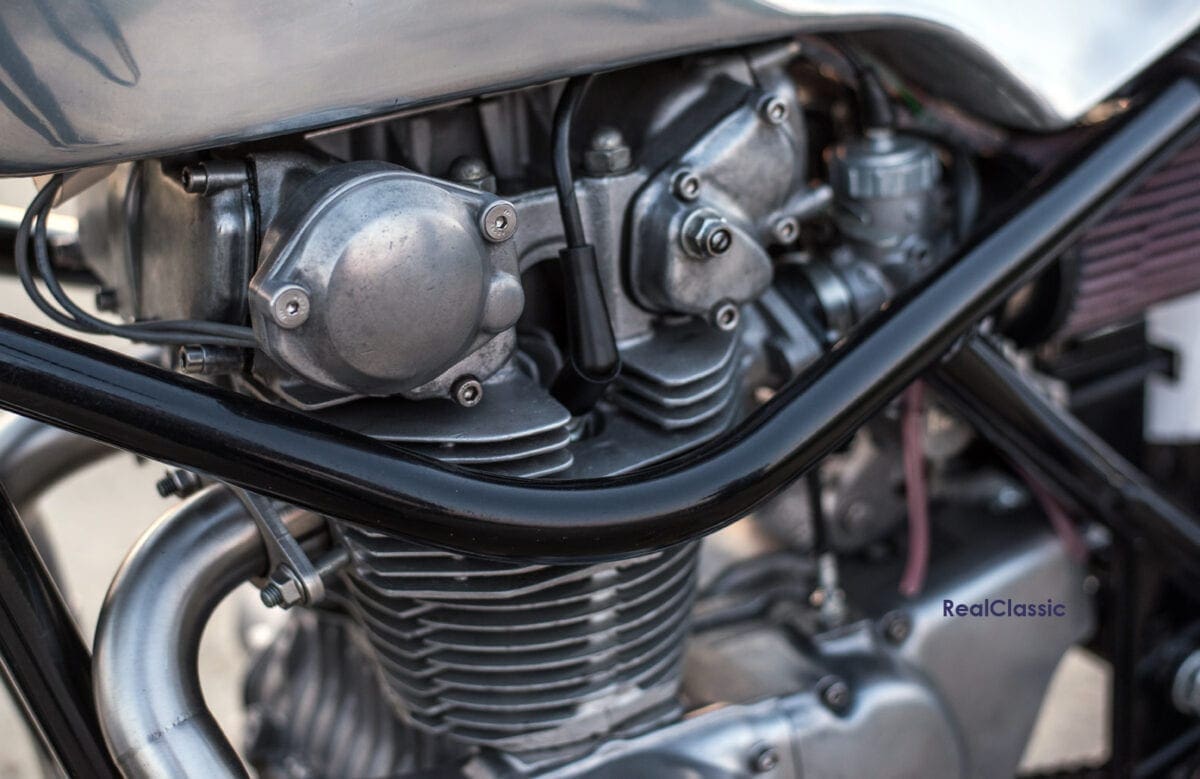

The CB’s oversquare 445cc vertical twin carried its cylinders upright, not inclined like Honda’s earlier twins. Even with a stroke of just 57.8mm it was still a tall engine for its time, equipped as it was with double overhead cams, carrying an appreciable amount of mass up top. The CB450 featured a 180-degree ‘one-up, one-down’ crank for better engine balance, although it was far from vibration-free in use.

In standard form the Black Bomber was just about capable of breaking the ton: entirely respectable for a bike of its class. Honda’s optimistic claims of a top speed of 112mph led to some criticism, however, when 102mph was the best anyone could achieve with a customer bike. The first four-speed gearbox was far from slick and involved some ill-placed ratios, hence the swap to a five-speed gearbox for 1967. With new carbs and some other tweaks, power rose from a claimed 43bhp to 45bhp at 9000rpm, and the second incarnation of the Black Bomber is generally accepted to be the better bike.

At that time, Honda had withdrawn from road-racing to concentrate on developing customer products, but that didn’t stop competitors adapting production machines to suit their needs. Racers soon spotted the potential in the CB450 and Honda were persuaded to provide some special components for Daytona in 1967. This resulted in the Hansen 450, which retained the unusual valvegear and survived revving to its 11,000rm redline with no discernible valve float. Hansen bumped compression slightly from 8.5:1 to 9.2:1, and fitted a hefty set of 35mm Keihin carbs. Cycle World reported that the result was an extremely tractable racebike; ‘almost no clutch slip is required to get the machine under way’, and it was surprisingly smooth with an ‘almost complete lack of vibration throughout the entire operating range.’ The Hansen Honda finished Daytona in 10th place.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the first Drixton Honda was being built in Milan by a pair of Australians and Othmar ‘Marly’ Drixl in 1968. Together, the two mechanics and the Swiss frame-maker transformed a CB450 streetbike into a world-class competitor. There wasn’t a whole heap of choice around for privateer racers in the 500 GP class in the late 1960s. The era of the booming Brit single was all but done and the inexpensive alternatives were over-stressed 350s. The affordable 445cc CB was a good candidate to be bored out, so Terry Dennehy and Ralph Hannan took it up to 462cc. They replaced the valvegear with conventional springs, ported the cylinder head, fitted Webco camshafts, Aermacchi pistons and a 32mm dual-throat Weber carb.

The engine mods certainly pepped up the CB’s performance but that only served to highlight the shortcomings of the roadster chassis. So Marly Drixl built his ‘bird-cage’ style frame with wrap-round top tubes, which carries the engine further forward than in the standard Honda chassis and usefully transfer some load to the front wheel. Drixl crafted the fuel and oil tanks, and the exhaust system was made by Rob North in UK.

The result was a privateer bike which barked as loud as the big dogs. The Drixton Honda finished fourth in the 1969 Italian 500 GP and was running in second place behind Ago’s MV in the East German GP when it ran out of petrol – Dennehey pushed it home for fifth place. By 1970 the engine had been further bored to a full 500cc. It sported beefed-up conrods, pistons and crankshaft and was fed by a 38mm Dell’Orto. It revved to 9800rpm, used a close-ratio five-speed gearbox cluster and weighed just 130kg. The frame also underwent some evolution for 1970, with the top tubes running over the top of the cylinder heads instead of wrapping around them. In its day, the Drixton 500 was the only Honda scoring points in the European premier class – rumour has it that Honda weren’t even aware of its existence at the time!

The result was a privateer bike which barked as loud as the big dogs. The Drixton Honda finished fourth in the 1969 Italian 500 GP and was running in second place behind Ago’s MV in the East German GP when it ran out of petrol – Dennehey pushed it home for fifth place. By 1970 the engine had been further bored to a full 500cc. It sported beefed-up conrods, pistons and crankshaft and was fed by a 38mm Dell’Orto. It revved to 9800rpm, used a close-ratio five-speed gearbox cluster and weighed just 130kg. The frame also underwent some evolution for 1970, with the top tubes running over the top of the cylinder heads instead of wrapping around them. In its day, the Drixton 500 was the only Honda scoring points in the European premier class – rumour has it that Honda weren’t even aware of its existence at the time!

The ‘Drixton’ name came from Drixl’s partnership with British dealer Sid Lawton, which supplied racing frames for Aermacchi engines. It was used on Drixl’s Hondas and has become widely adopted for the many replica frame built since. In all probability, Drixl only built three or four complete Drixton Hondas but his design was so effective that it thrives to this day on classic racing circuits in the UK, Europe and America.

In the 1990s Drixton replica frames were being built to order in Ireland and shipped worldwide. In the USA, Todd Henning blitzed the vintage racing scene with his fully-faired Drixton Honda. He pushed the CB’s engine output to 60bhp at the rear wheel (the standard bike was good for around 35bhp at the back), and regularly won the prestigious AHRMA Premier 500 class from 1994 until he stopped racing in 1999.

These days, you’ll still find Drixton Hondas scrapping at the front of the pack on either side of the Atlantic. Our feature bike wowed the crowds at the Winter Classic show a couple of years ago, owned by Robert who races one of his Hondas in classic competition. He built the second into the roadbike you see here.

‘I had a spare frame and engine after building my race bike,’ explains Robert. ‘I’ve been building this version for about six months. The engine is from 1968 and was originally in my race bike which finished third at Daytona in the AHRMA Sportsmans race in 2009.’

Very few changes were needed to civilise the racing CB for road use, says Robert. ‘The only difference in spec is the cams which are slightly milder to allow it to tick over. The cylinder head was ported by Todd Henning in the USA, and the 11:1 pistons are from him. The frame came from Ireland and is a copy of a late 1960s race frame. The four-leading shoe front brake is from a Suzuki GT750.’

Robert’s Drixton is equipped with a PAMCO electronic ignition system, Mikuni carbs and an NRP exhaust system. He left off the starter motor to save weight, which means there’s only a kick-starter, and ‘as with all the bike, I built the wiring loom myself. For road riding the seat could do with more padding but this is an on-going project.’

So would Robert recommend the Drixton set-up to other Honda owners? Certainly seems so. ‘With the engine higher and further forward than standard, and the whole thing lighter and stiffer, it handles superbly.’

Words by Rowena Hoseason

Photos by Joe Dick