A couple of months ago, our Ace Tester Paul Miles rode and reported on an excellently upgraded BSA B50SS. Paul reckoned it definitely deserved its Gold Star designation. No sooner had that magazine been delivered than international man of mystery Frank Melling popped up, expounding exactly the opposite opinion. Here’s Frank’s view of the B50, as it was when it was new…

Paul Miles and the much-modded B50 he tested

I read the B50 story in the November issue of RealClassic with particular interest because I was somewhat involved with BSA’s last 500 single. In fact, almost to my embarrassment in terms of how little riding ability I had, I was BSA’s last works rider. You can read how this happened in A Penguin in a Sparrow’s Nest.

The B50 which Paul Miles rode is a truly superb restoration and a great credit its owner/creator. Perhaps this is why Paul has been a little misled in his conclusions about the model as it was when new.

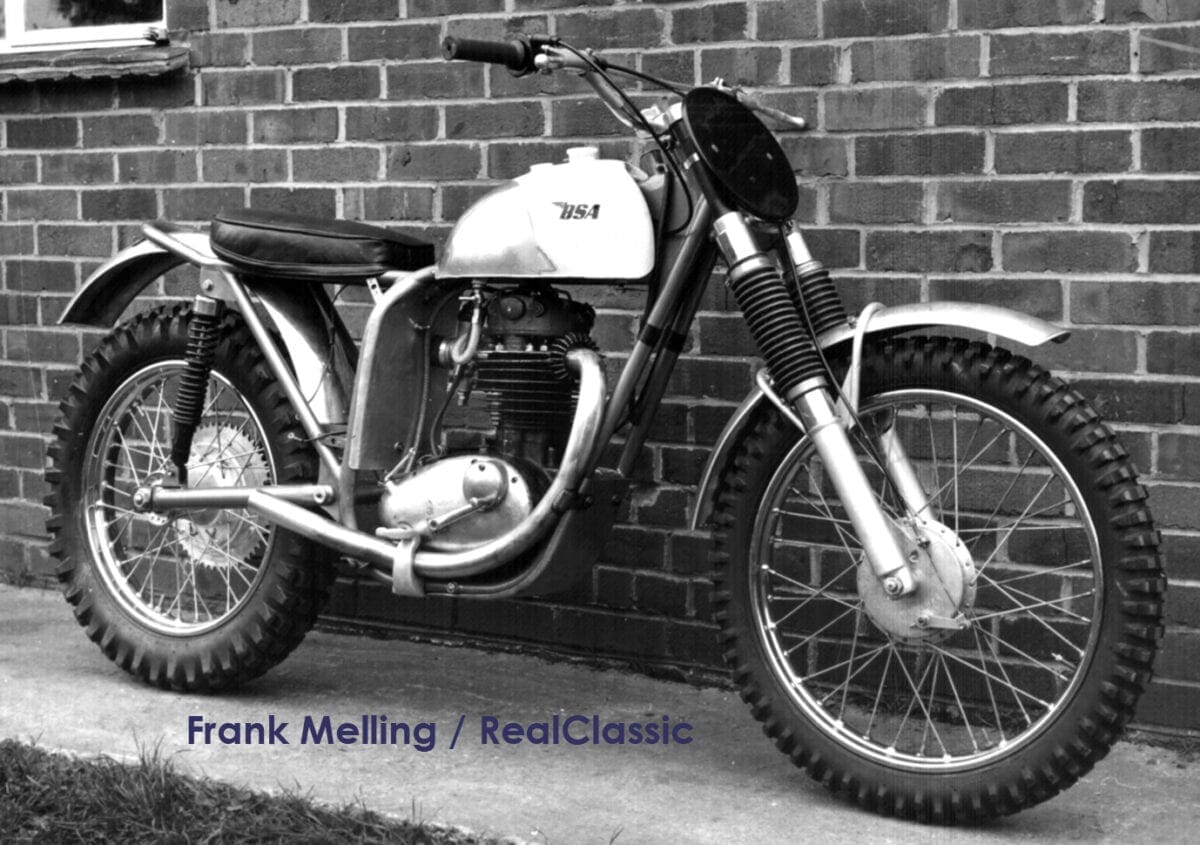

Frank’s factory BSA B50, back in the day

There never, ever was a B50SS which produced 34bhp straight off the production line. I can give you some actual figures of what the B50s did make and even these are ‘more or less’ because the power output varied bike to bike and day to day. My ‘second-level’ factory bike made a gnat’s eyelash under 33bhp, using Cyril Halliburn’s speedway cam. However, it was a missile off the line and gave me a lot more success than my riding ability merited. It was also reliable because, although the bike was factory maintained, it only went back to Small Heath every six or eight weeks rather being fettled every single weekend.

John Banks had the very best motocross engines and these knocked out a bit under 40bhp and lasted just a single GP because John revved the man-bits off them. A first-line factory MX engine managed around 36bhp. Bob Heath’s works B50 road racer, complete with ginormous Amal GP carb, was in the 45bhp range. So 34bhp from a bog standard B50SS road bike coming off the production line seems unlikely.

The fact that Paul could so easily start the B50 he rode, even with the assistance of electronic ignition, shows that it wasn’t making any power. No decent B50 can be started on the kick start because the engine requires a ridiculously high compression to work well and has light flywheels. Have a look at images of any works BSA, Cheney or CCM and you will see that they are universally sans kickstart.

Not for nothing did B50 riders cluster at the top of any hill in a motocross paddock because a downhill bump was the only way to fire them up. As Paul notes, they were normally a nightmare to start in roadgoing form when partially hot or, worse still, if they were stalled – so all credit to this bike’s builder.

Any decent B50 needed National Benzole five-star. This was a 101 octane fuel with each gallon containing enough lead to sink a boat full of environmentalists. Any attempt to run on mere 99 octane would be risking savage pinking and a melted piston. What was Paul’s test bike drinking? These days, a 50/50 mix of Shell Optimax and 100LL Avgas works rather well. (Not that I would know of course, because using Avgas would be very naughty and so on).

A good B50SS – and there weren’t many of them – would scrape 26-27bhp: they really were puppy-dog slow. Quality control was also beyond bad in the last days of BSA.

Umberslade Hall had nothing to do with ‘innovating’ the oil in the B50 frame. This concept was already common practice well before Slumberglade Hall was even thought of. It’s difficult to say who popularised the idea for production, because Moto Guzzi had used it in the 1950s, but I would like to claim credit for my sponsor, the genius Eric Cheney. In the early 1960s he had a DBD34-engined motocross machine which Jerry Scott rode to many successes and this was oil in the frame. Later, Eric built ‘Black Bess’ – a works-supported B44-engined bike. This became the Mk1 Victor. It too lacked a kick starter! All the four-stroke Rickman Metisses were oil in the frame too.

Umberslade Hall had nothing to do with ‘innovating’ the oil in the B50 frame. This concept was already common practice well before Slumberglade Hall was even thought of. It’s difficult to say who popularised the idea for production, because Moto Guzzi had used it in the 1950s, but I would like to claim credit for my sponsor, the genius Eric Cheney. In the early 1960s he had a DBD34-engined motocross machine which Jerry Scott rode to many successes and this was oil in the frame. Later, Eric built ‘Black Bess’ – a works-supported B44-engined bike. This became the Mk1 Victor. It too lacked a kick starter! All the four-stroke Rickman Metisses were oil in the frame too.

Much the same applies to cam adjustment for the rear chain. This idea was lifted directly from the Rickmans. Eric Cheney had a much better variation on the idea with a vernier cam on the rear wheel spindle. All this was happening whilst the Slumberglade Hall staff were still employed at Westland helicopters – where they should have stayed!

Mk1 Cheney-Victor

You can get the cylinder head of a B50 to be gas and oil tight – but it needs patience and skill: just what the engineer in the story clearly has in spades. On the B50s I’ve encountered, the gearbox is utter rubbish, the clutch is a disaster and the front brake doesn’t work. The Lucas electrics were only electrical on a very good day.

Riding any B50 road bike at the time was an utterly depressing experience. They looked dreadful; had appalling finish; were difficult to start; were politician-promise unreliable and the vibration would loosen your fillings. If there was any attempt to ride them hard (and yes I did) then the gearboxes broke. They were an authentic member of the Gold Star lineage in the same way that I might’ve won a Grand Prix on my B50. The only reason that the either the B50T or SS existed is that BSA owned the tooling and were desperate to sell anything which would keep the company alive.

The quotes from Cycle Guide magazine are very interesting. At the time, I wrote for Cycle Illustrated and Motorcycle World and I excoriated the B50. The end result was that I was given a works B50MX as an encouragement to shut up and toe the party line. I didn’t – but still got to race the factory bike. My best bet is that Cycle Guide was given a very, very carefully prepared B50 courtesy of the JoMo race shop. This was quite common practice at the time.

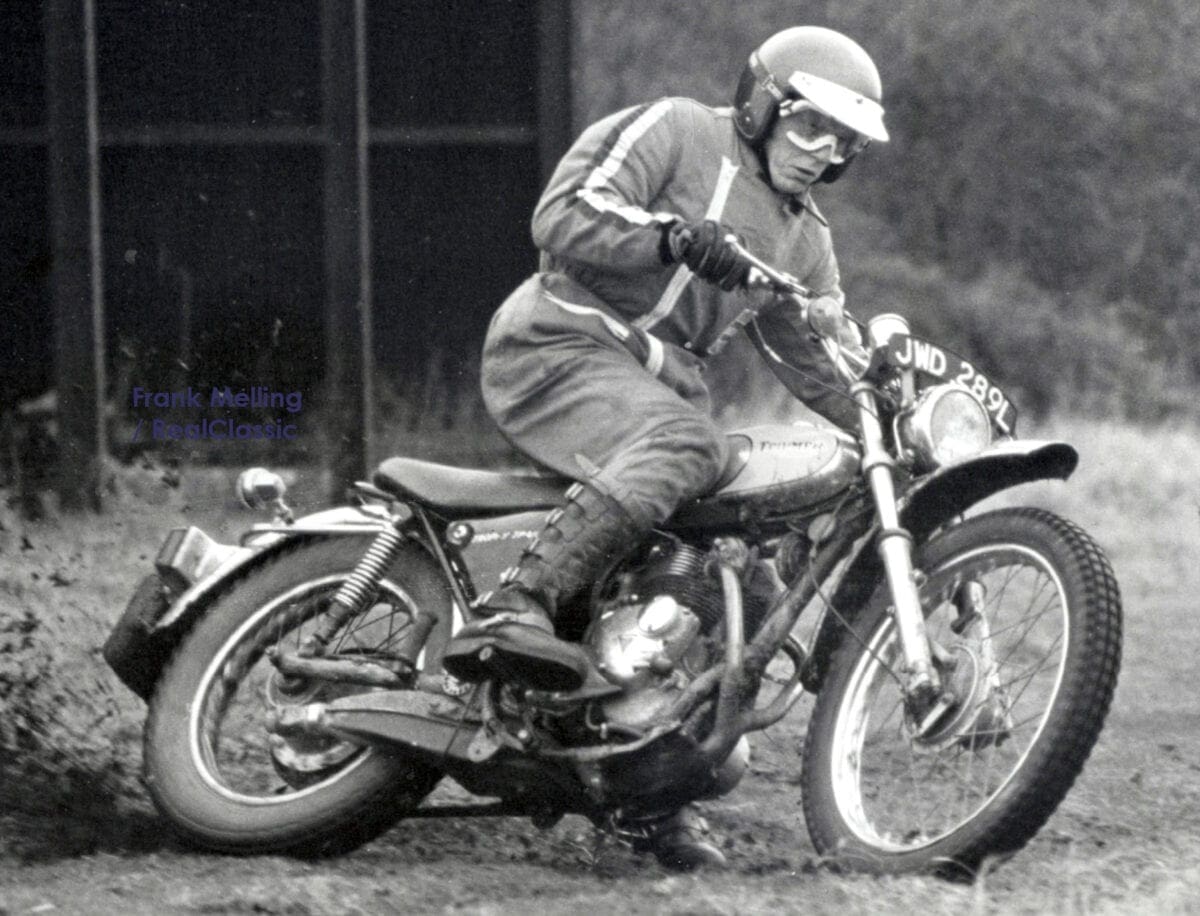

And now to the greatest calumny in the article. How dare the B50T be compared with the utterly wonderful Triumph TR5T? I say this as a BSA man through and through.

Once again, I was there and rode a factory Adventurer for Doug Hele. The TR5T does not give a ‘measly’ 30bhp – even as bog standard. My bike was effectively a single carb Daytona race engine and this knocked out something around 38bhp and was rocket-ship fast. The only thing it wouldn’t do better than a B50 was to out drag it from a standing start on mud.

Mr Melling took great care to run-in his Triumph TR5T gently

Otherwise, the TR5T would slaughter the B50T in the dirt and is also a vastly better road bike. And it starts when stalled. And it doesn’t break. And the gearbox works. And the clutch doesn’t slip. And it handles well. And I could go on for much longer…

There is also a sad footnote to the bike – and one which breaks my heart even today. Doug did a 560cc Adventurer with a five-speed gearbox. If BSA Group had fitted Japanese electrics to the bike, the Super TR5T was a whole generation more advanced than anything in the world. At the time, dual purpose bikes were the best-selling motorcycles in America. Put into production, the TR5T GP would have given BSA/Triumph two years’ breathing space to re-engineer the Rocket 3/Trident as a five speed, electric start, disc braked Superbike.

Instead, Lionel Jofeh put the money into the Ariel 3. You can read the story of this ill-fated three-wheeler in a forthcoming edition of RC.

——–

What do you think? Was BSA’s big single a non-starter? (Ahem). Or can modern technology transform the last Gold Star into a practical classic? Comments welcome below or on our Facebook page…

Words and photos by Frank Melling