While we celebrate the resurgence of modern Triumph motorcycles, it’s easy to overlook the marque’s major contribution to motorcycling itself which took place over a hundred years ago. Had it not been for Triumph’s first ‘era of greatness’, argues Timothy Pickering, the powered two-wheeler could have vanished from Britain’s roads long before the classic bike was invented…

Frank Melling’s otherwise excellent article about the otherwise excellent new Triumph Visitor Experience follows the lead of much of motorcycling literature and online sources nowadays, by dividing Triumph’s long history into two phases; a ‘modern’ era and a ‘classic’ era. The ‘classic’ era is widely understood to mean the Meriden-built twins of gifted despot Edward Turner.

Enjoy more RealClassic Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

It is beyond living memory now but, in contrast to the impression conveyed by the Triumph Visitor Experience exhibits, Triumph has altogether had three ‘eras of greatness’. In addition to that of Edward Turner’s twins (1936 to 1984), and the Hinckley era (1990 onwards), Triumph’s first great production era was that of Bettemann and Schulte from 1905 to 1925 when their own-engine 3.5hp long-tank singles were the British industry standard and a global benchmark for sturdiness and reliability.

The world is not short of glossy coffee-table books about Triumph motorcycles, yet the only work that adequately covers all three Triumph production eras in a single volume is The Triumph Story by David Minton. The narrative unfolded by Minton rightly starts not in 1936 but in the pioneer years of motor bicycles at the turn of the 20th century, when these new-fangled devices were nothing but playthings of a small and lunatic fringe. Minton describes this period as a time ‘when rich young men regarded mechanical defects as personal challenges to be overcome through strength of leg, wallet or character’.

The world is not short of glossy coffee-table books about Triumph motorcycles, yet the only work that adequately covers all three Triumph production eras in a single volume is The Triumph Story by David Minton. The narrative unfolded by Minton rightly starts not in 1936 but in the pioneer years of motor bicycles at the turn of the 20th century, when these new-fangled devices were nothing but playthings of a small and lunatic fringe. Minton describes this period as a time ‘when rich young men regarded mechanical defects as personal challenges to be overcome through strength of leg, wallet or character’.

Motorcycling itself was in grave danger at this time. There had been a big burst of enthusiasm for two-wheeled automobilism from around 1902. In response to the demand, almost anyone would bring over Belgian proprietary engines to knock together ill-considered devices that then caused endless frustration for their users. The fledgling industry soon went into a serious down-turn as customers stopped believing the exaggerated advertising claims of the makers, who either went broke or reverted to building bicycles.

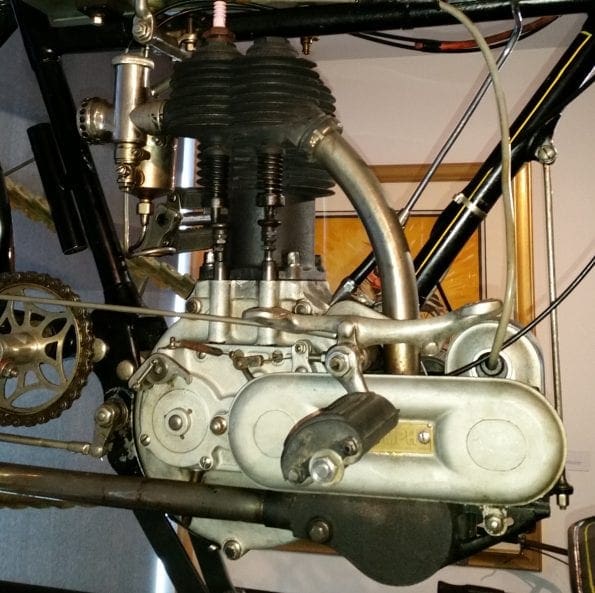

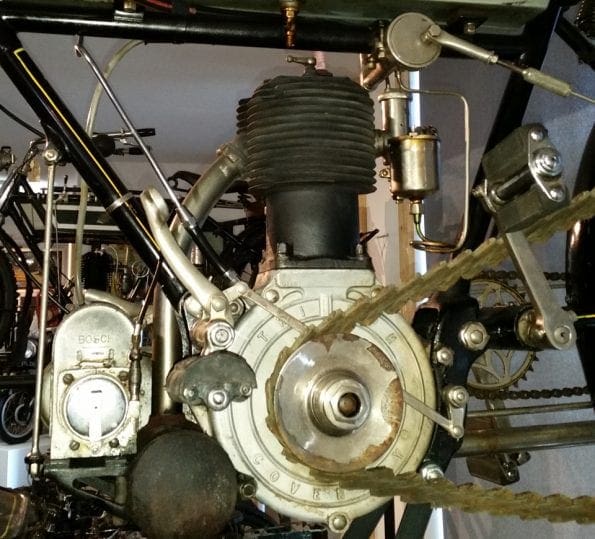

Coventry bicycle makers and Nuremburg expats Siegfried Bettemann and Mauritz Schulte had dabbled with a Minerva-powered device in 1902. Next they tried out the first JAP engine to emerge from Mr Prestwich’s works in Tottenham, but soon rejected it as also being a piece of crap. They resolved to design an engine of their own. The result was a handsome and sturdy MOTOR cycle (not a motor bicycle), the 3hp Triumph of 1905, that represents the first ever real machine for the masses produced by any British factory.

What was the impact of Bettemann’s and Schultze’s creation? Well, the general consensus among motoring historians and knowledgeable enthusiasts is that Triumph’s first own-brand engine saved the British motorcycle industry and gave it a future. Following the euphoria of the pioneering days of motorcycling, a sales slump had set in from 1904 onwards which made it clear that motorcycle manufacturers were not going to sell very many machines at all if custom remained limited to men strong in leg, wallet or character. To expand the market, motorcycling would need to appeal to an ‘average person’ looking not just for sport but for personal transport.

What was the impact of Bettemann’s and Schultze’s creation? Well, the general consensus among motoring historians and knowledgeable enthusiasts is that Triumph’s first own-brand engine saved the British motorcycle industry and gave it a future. Following the euphoria of the pioneering days of motorcycling, a sales slump had set in from 1904 onwards which made it clear that motorcycle manufacturers were not going to sell very many machines at all if custom remained limited to men strong in leg, wallet or character. To expand the market, motorcycling would need to appeal to an ‘average person’ looking not just for sport but for personal transport.

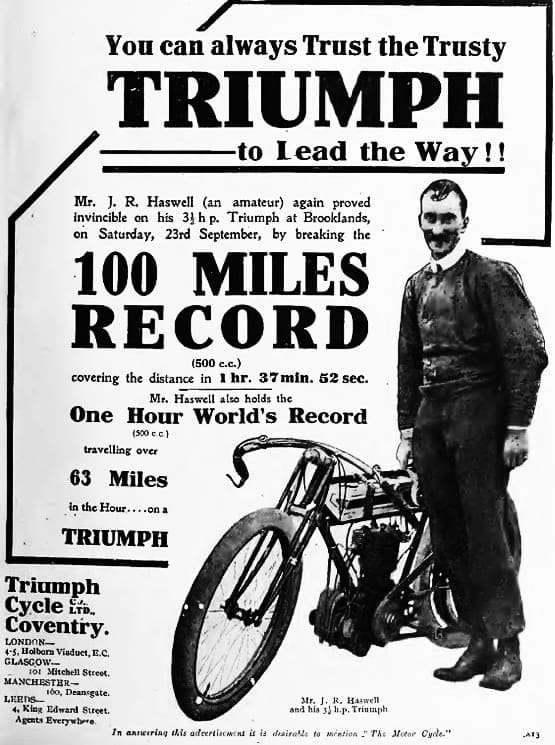

The famous motor-journalist Ixion in later life recalled that: ‘Magnates associated with rival firms have often frankly confessed that Schulte saved the industry from possible extinction in the early days, when a limited body of customers were growing somewhat weary of roadside trouble, weak climbing and the marketing of so many inadequately tested designs.’

The 3hp Triumph of 1905 was not without its flaws, however. In his 1920s memoirs Ixion reveals that he was on first-name terms with Schulte, and from time to time he and his riding friends were given various experimental and hush-hush two-wheeled devices to discreetly test and report back on. When Schulte let Ixion loose on the impressively simple, solid and attractive 3hp Triumph to rack up some serious miles, to their mutual horror he soon found that its promise faded very quickly. He wrote:

‘ They will forgive my saying after all these years that the first engine of their make that I owned was uncommonly bad. Delightful when new, it rapidly weakened down to the power of a cat and a half. Its soft valves pitted and scaled and warped with incredible rapidity. After 500 miles the compression became a minus quantity, and you could hardly get enough suck on the carburettor to start the engine up. But the firm realised these defects, and set their metallurgists to work. Year by year they have eliminated every possible cause for criticism, and today they enjoy such public confidence as few firms in any industry can command.’

They will forgive my saying after all these years that the first engine of their make that I owned was uncommonly bad. Delightful when new, it rapidly weakened down to the power of a cat and a half. Its soft valves pitted and scaled and warped with incredible rapidity. After 500 miles the compression became a minus quantity, and you could hardly get enough suck on the carburettor to start the engine up. But the firm realised these defects, and set their metallurgists to work. Year by year they have eliminated every possible cause for criticism, and today they enjoy such public confidence as few firms in any industry can command.’

So the big turn-around for the British industry came with the improved 3½hp Triumph in 1907, described by Ixion as ‘probably the first really excellent motorcycle ever built’.

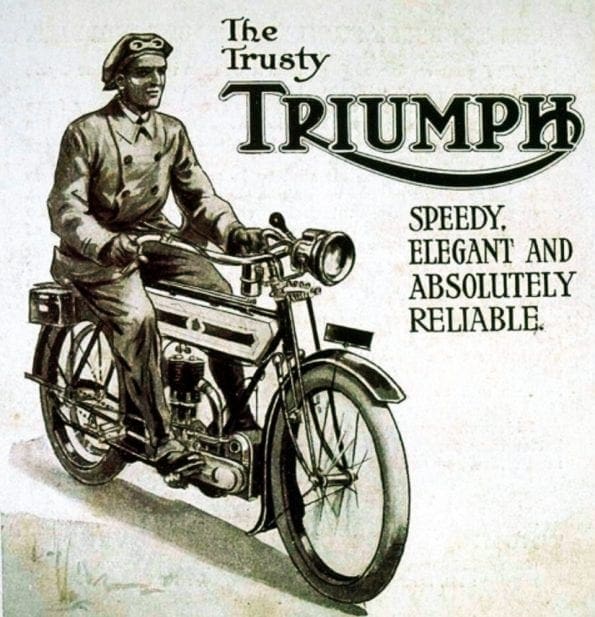

The ‘Trusty Triumph’ became the industry standard for the next two decades, and formed everybody’s ideal of what a ‘motor’ cycle (as opposed to motor-bicycle) should look and go like. The 1920 edition of a popular annual book Motorcycling Manual: All about the Motorcycle in Simple Language, opined that ‘the Triumph was the original successful single-cylinder machine’, and that ‘ten or twelve years ago’ (that is, in 1908 – 1910), ‘most newcomers to the motorcycling industry, and many of those already in existence, slavishly copied the Triumph design, on which they thought they could not improve’. By this time, the ‘Trusty Triumph’ had provided sterling military service that endeared it to a whole generation of riders.

A contemporary rider’s impression about the long-tank Triumphs of those pre-WWI days is provided by Irish enthusiast and amateur racer Noel Drury in reminiscences published in the VMCC newsletter a few years back.

‘The Triumph Co of Coventry made, I think, the best finished machine of that period. When they started they used in succession the 2hp Minerva, the 2½hp JAP (John A Prestwich & Co of Edmonton, London N, makers – 1904 2½hp JAP machine £36), the 3hp Belgian Kelecom engine, and then in 1905 they brought out their own make of engine with mechanically opened inlet valves and ball bearings on the pulley or drive side. A Bosch magneto was also fitted.

‘The Triumph Co of Coventry made, I think, the best finished machine of that period. When they started they used in succession the 2hp Minerva, the 2½hp JAP (John A Prestwich & Co of Edmonton, London N, makers – 1904 2½hp JAP machine £36), the 3hp Belgian Kelecom engine, and then in 1905 they brought out their own make of engine with mechanically opened inlet valves and ball bearings on the pulley or drive side. A Bosch magneto was also fitted.

‘They were fine machines and a great advance on everything else on the market at that time. The only snag was the design of spring forks that altered the trail angle at every movement and caused serious trouble when cornering fast. One of the most reliable and well-built machines of the early days was the Triumph and when they brought out their first all-Triumph machine both I and my brother Jack got them. The engines were much given to knocking on hills but I devised an adjustable jet which I could increase slightly in size to make the mixture richer while riding. All machines of this period suffered more or less from this trouble.

Jack and I went for a tour in England and decided to call at the Triumph works to have the machines checked over. We were received like royalty by Mr MJ Schulte, the Managing Director, and Frank Herbert, the Works Manager. My engine was entirely replaced by a new one as they said the original was not up to standard. Both machines were gone over, wheel and head bearings adjusted and lubricated, Jack’s engine stripped. After a final run by Frank Herbert the machines were handed over next morning, the bikes being marked ‘NO CHARGE’! One can’t imagine this being done now, 55 or more years later.’

This first era of greatness in Triumph’s history began to wane in the mid-1920s when, distracted by automobile manufacture, and perhaps also falling into the same trap as Henry Ford who stuck with his original Model T concept for far too long, the Triumph offerings were by now long in the tooth and outclassed by a new breed of ‘modern motorcycle’. Smaller (mostly 350cc), lighter, more nimble and more efficient, these represented a second wave in motorcycle design exemplified by AJS, Velocette, and Ariel.

This first era of greatness in Triumph’s history began to wane in the mid-1920s when, distracted by automobile manufacture, and perhaps also falling into the same trap as Henry Ford who stuck with his original Model T concept for far too long, the Triumph offerings were by now long in the tooth and outclassed by a new breed of ‘modern motorcycle’. Smaller (mostly 350cc), lighter, more nimble and more efficient, these represented a second wave in motorcycle design exemplified by AJS, Velocette, and Ariel.

A man named Val Page had a lot to do with several of these new machines, and Triumph in turn acquired his services in 1932. Change ensued that was long over-due. Triumph’s designs of the 1920s were mainly ones that came directly from the very dawn of serious motorcycling, but the days of heavyweight long-tank singles for workaday use were now numbered. Then the Great Depression came along, and only the really fit were going to survive.

And so it came to pass that the motorcycle side of the Triumph business was let go, in 1936, to a fellow named Jack Sangster. Who promptly revamped everything, and installed a young upstart named Edward Turner. The rest, well, you already know how that goes …

It is difficult to over-state the impact and the importance of the Triumph 3.5hp model in the history of motorcycling. It was the Triumph of Bettemann and Schulte which saved motorcycling from still-birth and breathed life into a whole industry. By all means go and enjoy the Triumph Visitor Experience. If you’ve read this article first, you’ll be able to fill in some of the blanks.

——–

Words by Timothy Pickering

Illustrations: Tim Pickering / Richard Jones / RC RChive / Bonhams auctioneers