Last month, we posed the question ‘what originally inspired you to take to two wheels?’ Derek Reynolds reveals that his lifetime with classic bikes began with a desire for a longer lunch break…

I had no previous interest or desire to ride a motorcycle before the age of 16, nor had any members of my family before me. My best pal’s dad rode a small Gilera to work in the 1950s and his bike was kept in the hall passage, which we had to squeeze past on each visit. It smelled tantalisingly of petrol and oil, but did not instil any further interest or involvement – until aged 16, when I left London and began work on a farm in rural Dorset.

There were two farms owned by two brothers. We lived on one and worked on the other which was a mile away and, significantly, down a very steep hill. All our meals were on the farm we lived at and my only form of transport was a pedal bike. So that hill proved a challenge which defeated any riding up it. It demanded walking up! Jack the pigman suggested that I get a little motorbike to overcome that hill and so I caught a bus to Yeovil to peruse the local motorcycle emporium. I gazed at a range of bikes of below 250cc, as that was the upper limit for a learner rider in the early 1960s. I ended up purchasing a Francis-Barnett Plover with a 150cc Villiers engine for the princely sum of £30, plus a further £5 for tax – and insurance!

There were two farms owned by two brothers. We lived on one and worked on the other which was a mile away and, significantly, down a very steep hill. All our meals were on the farm we lived at and my only form of transport was a pedal bike. So that hill proved a challenge which defeated any riding up it. It demanded walking up! Jack the pigman suggested that I get a little motorbike to overcome that hill and so I caught a bus to Yeovil to peruse the local motorcycle emporium. I gazed at a range of bikes of below 250cc, as that was the upper limit for a learner rider in the early 1960s. I ended up purchasing a Francis-Barnett Plover with a 150cc Villiers engine for the princely sum of £30, plus a further £5 for tax – and insurance!

Not only could I extend my time at the lunch table, but I could also ride farther than possible on the push bike. The exhilaration of travelling at 45mph downhill and 20mph up (the Plover was a tired machine) was intoxicating.

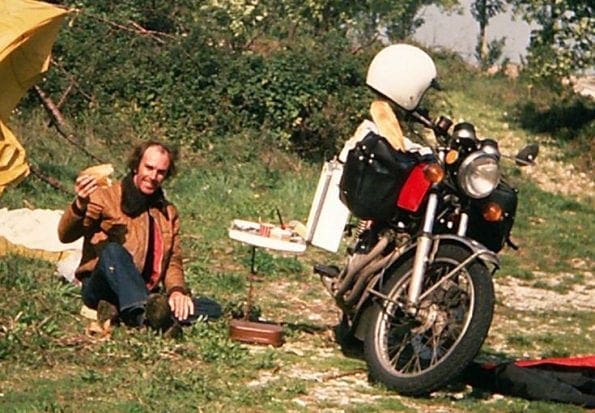

That experience has been with me ever since and remains with me still in my 70th year. Many bikes – some capable of over 100mph – which have passed through my hands since. Life in the saddle has enriched the past 54 years in priceless quantities: the pure thrill of balance, executing a perfect curve, and being in the wind experiencing the wide uninterrupted view of all that surrounds us unencumbered by windscreen pillars, headrests and passengers; the immediate contact with the elements and the smells of the countryside be it crops ripening, new mown hay, autumn leaves, and even crisp frosty air.

That experience has been with me ever since and remains with me still in my 70th year. Many bikes – some capable of over 100mph – which have passed through my hands since. Life in the saddle has enriched the past 54 years in priceless quantities: the pure thrill of balance, executing a perfect curve, and being in the wind experiencing the wide uninterrupted view of all that surrounds us unencumbered by windscreen pillars, headrests and passengers; the immediate contact with the elements and the smells of the countryside be it crops ripening, new mown hay, autumn leaves, and even crisp frosty air.

From an early age when given a Meccano set to ‘play’ with, I had an enduring fixation with the mechanics of how things were put together, and how they worked. Sadly, there were some things that got taken apart and did not get put back together, a trait that lingers to this day!

This fascination of the mechanical led me to strip down the Plover’s gearbox to discover why it made a racket in first gear, and I replaced a pinion with one tooth missing. Then it was piston rings, and then my BSA C15 also got rings and valves attended to. Workshop manuals were absorbed, and exploded drawings studied studiously. The Honda CB72 had gearbox issues too, and to get to that, the horizontal crankcase had to be split.

One of my first and treasured books was Phil Irving’s Tuning For Speed. I still have it (along with my schoolboy Ian Allan’s British Railway Locomotives combined volume) and many other books on motorcycle maintenance collected since. Spannering and fettling became second nature, and the only time any external workshop has touched any of my bikes was for machining that I had no equipment for – only twice ever; a rebore on the BSA Road Rocket, and a crankpin re-assembly on a BSA B31.

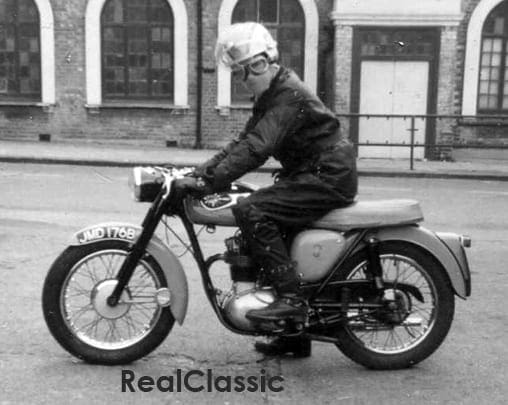

Having twice ridden the Plover in those early months of motorcycling from Somerset to North London (my parents’ home), I felt it needed replacing with something more powerful and reliable. Enter one brand new BSA C15, and the Plover taken in part exchange, valued at £30! In comparison to the two-stroke, the four-stroke BSA 250 was a revelation in mechanical smoothness and reliability, and I rode it everywhere.

Then a chance meeting at a set of traffic lights with my old school pal Keith who was mounted on a Honda CB160 set my desires on something that could keep up when we went out together. Next up – a Honda CB72.

Keith also traded up to a CB72, and his dad traded his Gilera in for a CB77, the 305cc Honda. I well remember meeting Keith outside his house for a run up the A10, when his dad came out and said ‘wait for me!’ And out he emerged wearing his ex-WW2 despatch rider’s storm-coat, woollen beret and Mk8 goggles. ‘Oh no!’ we thought, we’re going to be held up, with his dad plodding along expecting us to ride to the letter of the law. Was I ever wrong! He disappeared up the road like a banshee, and led us all the way with us struggling to keep up.

Keith also traded up to a CB72, and his dad traded his Gilera in for a CB77, the 305cc Honda. I well remember meeting Keith outside his house for a run up the A10, when his dad came out and said ‘wait for me!’ And out he emerged wearing his ex-WW2 despatch rider’s storm-coat, woollen beret and Mk8 goggles. ‘Oh no!’ we thought, we’re going to be held up, with his dad plodding along expecting us to ride to the letter of the law. Was I ever wrong! He disappeared up the road like a banshee, and led us all the way with us struggling to keep up.

Later I sold the Honda to help fund my next bike, a rebuilt (to civilian spec) 750cc Harley-Davidson from Fred Warr’s shop in the Lower King’s Road, Chelsea. I had read a couple of reports on Harleys. Back in the mid- 1960s they were as rare as hen’s teeth on our roads, and the glitz and glamour that went with ‘buckets of torque’ intrigued and beguiled me. This was a railway locomotive on two wheels and I had to have one.

Enter KPL 736. Black stove-enamelled frame, tank and mudguards, chrome rims and chrome springer front forks, windscreen with spot and fog lamps, and footboards (!); a big ‘buddy’ seat, chrome crash bars and white hard panniers, a big speedo on top of the tank with two almond ‘eyes’ that lit up when the ignition was switched on, but most of all ‘that’ sound – putata – putata – putata as it ticked over. I soon mastered the foot clutch and hand-change after a short ride on the pillion with Fred at the controls.

For the next five years that Harley took me everywhere. It never broke down, and never missed a beat. It wasn’t powerful, it wasn’t fast. In fact, it introduced me to that very comfortable cruising speed of 50 to 55mph, along with admiring looks from girls, petrol pump attendants (when they still attended) wanting to know all about the bike, through to little old ladies oohing and aahing, and men who claimed they saw them tow tanks out of ditches in the theatre of war. How tall tales grow with the passing of time. So many stories, so many questions. It was glorious.

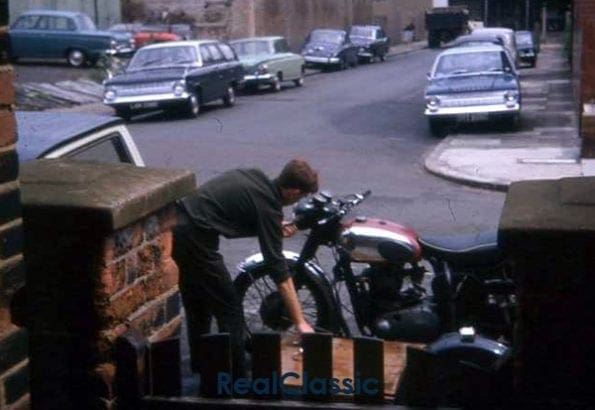

Through ice and snow that Harley 45 took me all over, even to the Isle of Man TT in 1967. Then, as a secondary machine, my pal Steve and I purchased a BSA A10 Road Rocket with child/adult sidecar that had been languishing in the works car park where it had attracted the attention of a vagrant who had used the sidecar as a doss house. It was full of fag ends and bottles. We negotiated a price from the real owner, and for £5 we had the basis of a holiday outfit to tour Cornwall.

That Cornish tour included re-designing the nose of the Canterbury against the front of a Riley 1.5 when our waterlogged brakes failed to stop us on a downhill single track road. We’d stormed through the ford beside Tarr steps in grand style… after which the Canterbury was scrapped to be replaced with a Steib and drifting on wet roundabouts became the norm – huge fun. The Road Rocket did see solo use again, but was jinxed with tyre failures. Then one day on an early turn at work, riding along a dark and misty country lane, I met with a fallen tree across the road. The impact bent the front forks, put stitches in my chin, and the A10 was sold for spares.

That Cornish tour included re-designing the nose of the Canterbury against the front of a Riley 1.5 when our waterlogged brakes failed to stop us on a downhill single track road. We’d stormed through the ford beside Tarr steps in grand style… after which the Canterbury was scrapped to be replaced with a Steib and drifting on wet roundabouts became the norm – huge fun. The Road Rocket did see solo use again, but was jinxed with tyre failures. Then one day on an early turn at work, riding along a dark and misty country lane, I met with a fallen tree across the road. The impact bent the front forks, put stitches in my chin, and the A10 was sold for spares.

The Harley was also sold after a strip down and a failed attempt at resurrecting to working condition, and I resorted to moped power in the form of a two-speed Puch. That was followed by a Honda CB125S, then a Yamaha DT175 (much trail riding done), then a Honda 400/4 with which I began despatch riding.

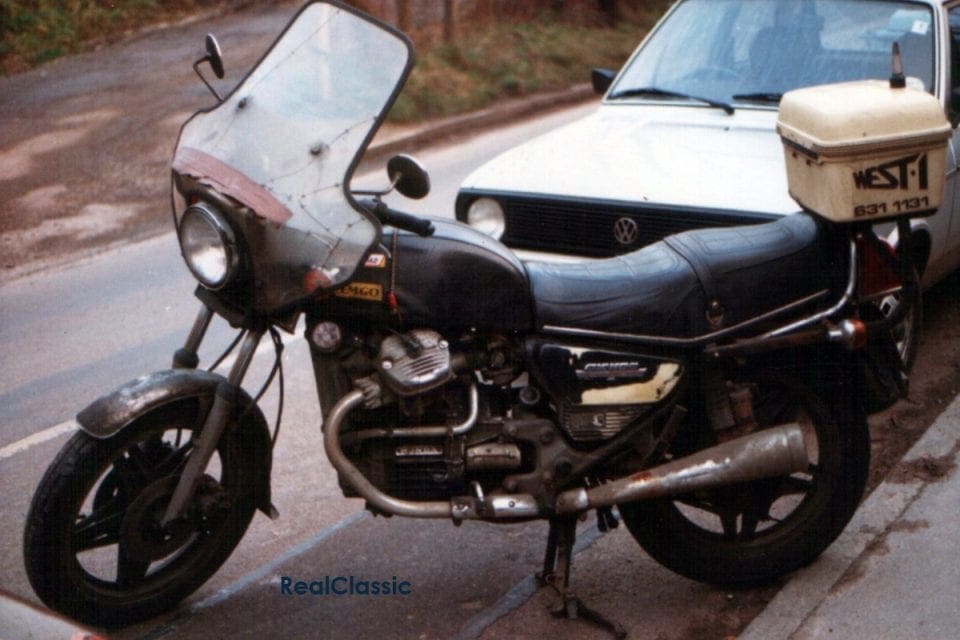

That was replaced with a succession of Honda CX500s, a BMW R80/7, and Moto Guzzi V50 Mk3, the last sold as a running machine with over 300,000 miles to its credit. Along the way these were joined by my late pal Steve’s Ducati 250 and a Guzzi Le Mans Mk2. These I still have, and in turn they have been joined by an East German stinkwheel in the form of an MZ ES125/1 from 1971. I have a soft spot for the uglies.

I have never owned machine tools, nor anywhere to use them. Garden sheds of various sizes have been my fettling shops, and mostly the bikes have been worked on outside, and kept outside open to the varieties of weather. So when I see double garages with lathes and milling machines I do get a little envious at times. But you work with what you have, and that’s enough to keep me in the wind, soaking up memories and adding a few more with each ride.

———-

Words and photos by Derek Reynolds

There are more motorcycling reminiscences in the June issue of RealClassic magazine