In the February issue of RealClassic, Dave Bushell noted that ‘my pre-war Scotts and, I think, most girder-forked machines, have their front brake arms facing forward from the pivot point. My post-war Scotts with telescopic forks have them facing rearwards, as do most other makes with some exceptions. If forward facing brake arms provide better braking, why did manufacturers reverse them on later models?’

This observation provoked a flurry of correspondence, quite a bit of which you’ll find in the March magazine. RC regular Dave Blanchard (there are two different Daves involved here!) expended some not inconsiderable intellectual energy on the subject, and here’s what he came up with…

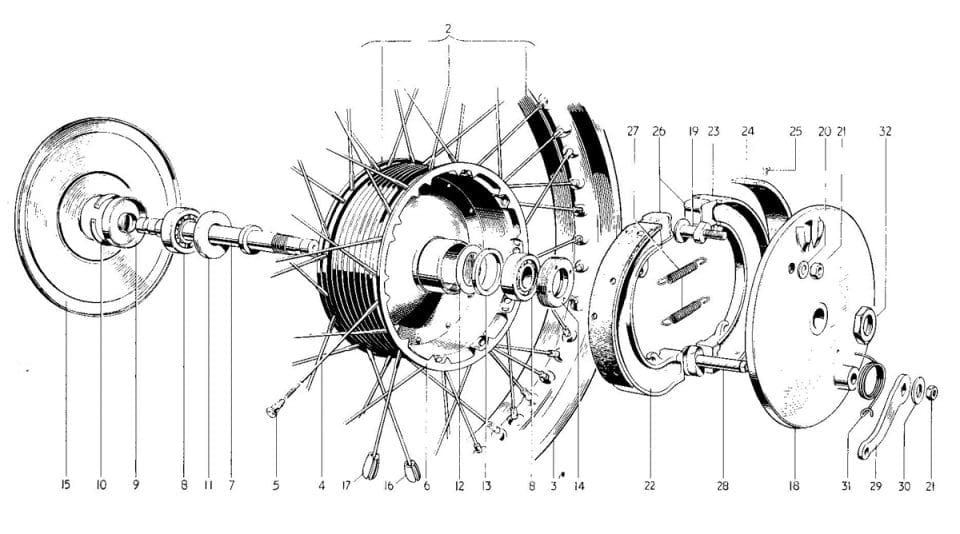

Dave Bushell’s experiment which involved reversing the twin brake plates on his Birmingham Scott (with claimed better braking) is a little obscure to me because I am not that sure what his Scott’s brake drum, shoes and linings actually look like and what condition they’re in. Using shoes in a different drum that they had not been used in before ‘should cause less friction’ because of high spots or mismatching of the surface area so should not perform as desired. I think Dave’s summing up – that the cam lobe nearest the wheel spindle exerting better leverage and power on the shoe – is incorrect. Whichever way the brake arm or cam moves, it is always the cam lobe ‘furthest’ from the shoe fulcrum (pivot) that will exert greatest leverage.

Archimedes’ ‘law of the lever’ is the key. A lever is also known in the motor and some building trades as ‘a Paddy Jack’. The further away from the fulcrum the applied effort is, the easier it is to move the load or exert pressure: in this case on the brake shoe. Think of the brake shoe as a wheelbarrow. The wheel is the fulcrum (fixed pivot on the brake plate). The load is the brake shoe pressing on the drum. The effort is the force applied to the brake arm. It becomes clear that the longer the wheel barrow handles are then the easier it is to lift the load… or in this case, press the brake shoe lining into the drum.

This all applies exactly as stated when the wheel or drum is static and not revolving. But! When a drum is rotating another factor applies which is called ‘wrapping’. This has nothing to do with Christmas parcels or music. It is the phenomenon of the leading shoe being pulled tighter into the drum due to rotation. This is a form of servo action and will happen to all leading shoes, but not trailing ones, unless you are rolling backwards: then the trailing shoe becomes the leading shoe (in a single leading shoe design).

If you design the brake so that the cam lobe furthest from the fulcrum pushes against the leading shoe when rotating forwards, then this will give more bite and should give better braking. This is due to the greater leverage plus the servo / wrapping action. Consequence? The leading lining wears out before the trailing one (not at all unusual). So maybe the better option would be to have greatest leverage (cam lobe still furthest from fulcrum point) pushing on the trailing shoe. Then slightly more even wear between linings would result.

The position of the operating cam on the brake plate (either in front of or behind the fork legs) and the positioning of the brake arm forward facing or rearward pointing can make a difference in some cases, due to differing leverage on one of the cam lobes. But not a lot.

Some girder-fork front brake cables have a short outer and longer inner wire depending on where the anchor lug for the outer Bowden cable is positioned. Most telescopic-fork front brake cables have a fairly long outer cable due to the anchor lug being on or near the brake plate itself. An outer Bowden cable always suffers from some compression because it is constructed akin to a coil spring and will compress somewhat under load. So the shorter you can make the outer cable the less spongy feel there will be to the brake action. Conversely, the inner wire will always want to stretch under load and this also can add to a spongy feel.

Some girder-fork front brake cables have a short outer and longer inner wire depending on where the anchor lug for the outer Bowden cable is positioned. Most telescopic-fork front brake cables have a fairly long outer cable due to the anchor lug being on or near the brake plate itself. An outer Bowden cable always suffers from some compression because it is constructed akin to a coil spring and will compress somewhat under load. So the shorter you can make the outer cable the less spongy feel there will be to the brake action. Conversely, the inner wire will always want to stretch under load and this also can add to a spongy feel.

I think that with girder forks it was easier and more convenient to site the cable run down the forward (front) face of the forks on several models, but not all manufacturers did this. With telescopic forks it looks far neater to have a cable run behind the fork leg with nothing flapping about up front. Remember that aesthetically-pleasing looks were important to sales of motorcycles back then. Refer to some old manufacturers brochures and in some cases you will see the bikes photographed without cables fitted, because looping cables do not look very tidy. That’s also one of the reasons Edward Turner tortuously routed cables through the Triumph twins’ beautiful nacelle. But whether the brake arm points forwards or backwards there should not be a great deal of difference in overall retardation.

To get more deceleration some of those 1930s road racers fitted extra-long handlebar brake levers to increase braking power. This does give more leverage and pushes the brake shoes into the drum a fair bit harder. But this is not good practice! It loads up the inner cable far too much so that strain and then breakage is more likely. It’s much safer to have a longer lever arm on the brake plate with less load going on the inner wire.

To get more deceleration some of those 1930s road racers fitted extra-long handlebar brake levers to increase braking power. This does give more leverage and pushes the brake shoes into the drum a fair bit harder. But this is not good practice! It loads up the inner cable far too much so that strain and then breakage is more likely. It’s much safer to have a longer lever arm on the brake plate with less load going on the inner wire.

If you really want to improve your braking power, without the expense of fitting a twin leading shoe back plate or wish to retain a standard appearance, then convert your shoes to the fully floating design, just like Triumph did around 1962 on their range of bikes. Have a look at how the fully floating shoes work by consulting any Triumph or BSA brochure from the 1960s to see how they did it.

I have modified several of our bikes in this way in the past, with good results. The fixed pivot on the shoe needs filing and a steel plate fitting so that the shoe can slide and centralise easily. The brake lining needs moving around on the shoe (or shortening in some cases) so that a clear gap is visible on the ‘leading edges’ of the trailing and leading shoes. Get expert help if this seems a little too confusing to understand: don’t take chances by guesswork.

I have modified several of our bikes in this way in the past, with good results. The fixed pivot on the shoe needs filing and a steel plate fitting so that the shoe can slide and centralise easily. The brake lining needs moving around on the shoe (or shortening in some cases) so that a clear gap is visible on the ‘leading edges’ of the trailing and leading shoes. Get expert help if this seems a little too confusing to understand: don’t take chances by guesswork.

———–

Extra advice from reader Simon Kling:

Keep the bowden cable well lubed. The friction in the cable takes a % of the hand lever force, because the squirly outer pushes hard against the inner as the cable loads up. The telescopic fork lever set-up prevents oil from the cable running along the brake arm into the drum, as uphill.

———–

If you’re looking for more detail about setting up drum brakes on classic bikes, this site provides lots of detail and some excellent disgrams.

Any other suggestions for improving drum brakes? Comment below or on Facebook.

(And no, we’d never heard of a lever being a ‘Paddy Jack’ before, either…)