Bob Bagshaw recalls what it was like to ride a motorcycle back in the immediate post-war period. First of all, you had to get kitted out correctly…

Demob came and with the bike in mind I chose a trench coat as part of my demob outfit. It was time to kit out. There were no leathers as yet, Barbours were all being exported and helmets were mostly of the steel variety. So I bought one of those caps with the peak at the back, a pair of pre-war vented flying goggles, a pair of flying gauntlets with silk inners which I had somehow misplaced when returning my flying gear (RAF Form 664b dealt with this).

For the all-weather riding which became mandatory with my civvy job, I bought a pair of big thigh waders which I could wear over my shoes and, initially, a surplus oilskin gas cape complete with hump for back-pack and gas mitts, with thumb and forefinger only, to cover my gloves. It certainly kept the rain out but looked odd and had a tendency to leak a bit round the neck. I eventually replaced it with a plasticised FAA flight deck coat, but the gas cape made a very good bike cover if you threaded the bars through the sleeves…

The majority of bikers did not have access to a garage so most maintenance was done in the open air and was almost exclusively a DIY job. Unless it was a big job on one of the newer bikes, the dealers didn’t want to know. Repairs just weren’t worth it when you could pick up another ex-WD or secondhand bike for next to nothing. So it often happened – cases were separated using the screwdriver / chisel and hammer method, nuts and bolts tackled and beautifully rounded with the Woolies adjustable, screws mangled with a specially blunted screwdriver guaranteed to slip. OK, oil went into the engine and possibly into the gearbox but girder forks were a pain and what was that grease gun thingy for? This is how the ‘truth’ that all British bikes leaked oil became established. One wonders why!

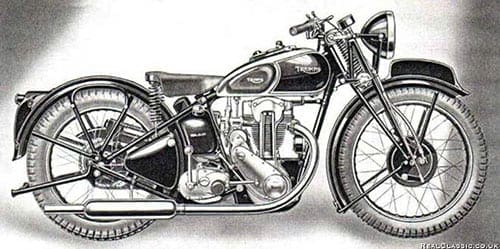

Quality Triumphs on …

I was still on a provisional licence at this time, for although the tests had re-started in 1946, it took a long time to get the ‘stations’ established, manned and up and running with long waiting lists. If you’d held a licence before the war or held a services one, you could get a licence without a test. If you had held a provisional for more than six months you could ride without L-plates until your test. I took mine in 1948 on a wet day and the test course was a figure-of-eight with two right-hand turns across a busy road, paved with the notorious wooden blocks which gave about as much traction as a well-greased ice rink. I passed but the examiner admonished; ‘watch it. You’re driving to GO not to STOP…’

I kept my Triumph 3HW for about four years during which time it lived up to its tough reputation on two occasions. Once I rode it for about 15 miles without any oil in the gearbox due to clipping the end off an acorn nut underneath. The other time I lost nearly all the engine oil when the flexible connection between the scavenge side and the rocker box split. I didn’t realise this until the back end stepped out on a dry road corner – the back tyre was totally oil-soaked. How long I had ridden without oil, I had no idea.

I fitted a civilised pillion to the bike and used it whilst courting as one did in those days. Alas, all good things come to an end. The eye doctor’s orders not to ride (due to the effects of my being slightly blown up when acting as an armourer ‘s assistant), and an impending engagement, meant the bike had to go. So I sold it to a mate who upped the gearing to Tiger 80 ratios then slapped a child/adult chair on it – and it never jibbed.

A Life With Classic Bikes Triumph 2H

I was bikeless for about three years then when my brother went to Canada for his RAF Navigator training, I inherited his 1937 Triumph 250cc 2H which was in a typical state of neglect but still started first time. I fitted a windscreen and legs shields plus skiing goggles over my specs so that I could ride it. I was convinced that when I rode it over potholes I could hear the crankshaft jumping up and down. Soon after I adopted it, the primary chain came out through the case – so I went to the breakers for a spare. I couldn’t find a two-piece replacement rocker box assembly for my now four-broken-piece one, which was held together with Hermatite red gasket goo.

The spring loaded, telescopic pushrod tubes, which had to be compressed to adjust the tappets, held by a screwdriver in the fins; could take the ends of your fingers off if it slipped. The tank panel was a bit of a fiddle to refit when lifting the tank (drained), but the wander light / instrument bulb was very useful. Experience revealed that the slope of the petrol tank at the rear was just right to drip rainwater into the carb – cured by installing a glucose tin shield. It also transpired that the breather hole in the contact breaker cover had to be at the top and not near the primary chaincase, or it also filled with rainwater.

Despite this, the 2H bike soldiered on in all weathers, rarely needing more than a couple of kicks to fire up. It also did about 80mpg and was as brisk as the current 250s. It seemed to prefer the National Benzine brand of petrol out of all the many that were available. I also treated myself to one of the first Everoak peaked helmets thus eliminating the Chinese headband torture which occurred as my old flat cap shrank in the rain.

I finally decided to do something about the Triumph’s bottom end so I approached Billy Briggs of Salford, the local Triumph man. He told me it wasn’t worth me bringing the bike in for him to fix, but to bring the flywheels in and he would do the big end and sell me the mains. This meant I had to dismantle the engine right down by myself, which I had never done before. By borrowing my uncle’s garage and, with the manual in one hand and a spanner in the other, I coped, spreading everything out labelled and in order. Thanks be that the gearbox was separate! Humping a set of flywheels on the buses is not a task to be taken on lightly…

A Life With Classic Bikes

The period between the end of the war and the 1960s was when practically anything with two wheels would sell, so all the old established makes reappeared for a time. The bikes all sprouted teles, first with solid rear ends then plunger suspension and finally swinging arms and twin shocks. With a couple of famous exceptions most common models were initially the iron barrel singles, still simple to work on. Models proliferated with a thriving new and secondhand market developing, and nearly everyone jumping on the multi-pot bandwagon.

There was not much competition at first. Everyone had their favourite marques and British bikes were very popular in the States which was the target market. So apart from increasing capacities and changing the gearchange and brakes over to the wrong sides, there was not much incentive for the manufacturers to do much more than cosmetic updates. However, the gradual increase in the availability of new and used cars (and especially the introduction of the Mini) were significant contributions to the start of the demise of the motor cycle industry – not just here but generally, especially in countries where the weather could be quite naff.

Bikes were no longer almost a must-have to get to work, as it had been, especially if the public transport was inconvenient or expensive. They had been practically essential if you worked shifts and out of town, as I did. In the later decades of the 20th century demand dwindled and the lack of investment, which seemed to prevail in the British motor industry, led to amalgamations and closures. The only large opening for two wheels was in the tiddler commuter field – hence Mr Honda ‘s international success. The arrival of the sorted, second generation of bigger Japanese bikes spelled curtains for almost all the old, established manufacturers except where their industries were ‘protected’ From now on, the big stuff was ridden mainly for pleasure, with the car for family use and as a fall-back when the weather turned nasty.

That was true for me too. My first ‘bike-life’ came to an end in typical fashion with an increasing family and our first car.

Next time: a return to motorcycling in later life…