Bob Bagshaw recalls a riding life with classic motorcycles, starting with his war years and first British bikes…

As I reach my four score years and ten I thought my experiences with motor vehicles and the gentle art of motorcycling might interest some of the younger readers — say those aged around 60 or so…

My earliest recollection was in the late 1920s, riding in the chair of my uncle’s 3½hp RAC BSA combo. This was quite a thing as there were not that many private vehicles about. I lived in a typical Manchester neighbourhood of terraced houses and in the surrounding streets there were only about four cars but several motorbikes and quite a few combinations, many of which swapped the passenger carrier for a flat tradesman’s box during the week. Mains electricity was the new thing. It’s really hard to believe there were no TVs, jets, computers or central heating. Most cameras were of the box type and very few folk had private phones. We had to use the old red phone boxes with the A and B buttons and a stack of pennies. By the end of the 1930s things were easing slightly out of the depression but cars were still the province of the much better off.

The personal transport situation was reflected when I joined up. In 1943 aged 18, I volunteered for aircrew. Of my intake group of 60, only ten could drive either a car or bike and most of these were ex-policemen. It now seems incredible that a 20 year old could fly a Lancaster on ops but had no licence for a car or bike. Just as the war in Europe was ending, I was finally trained as a flight engineer on Sunderlands, to go to the Pacific. Most of our group didn’t fancy signing on for a spell so were made redundant and finished up doing all sorts of odds and ends of jobs until demob. However help was at hand to minimise the frustration – MOTORBIKES.

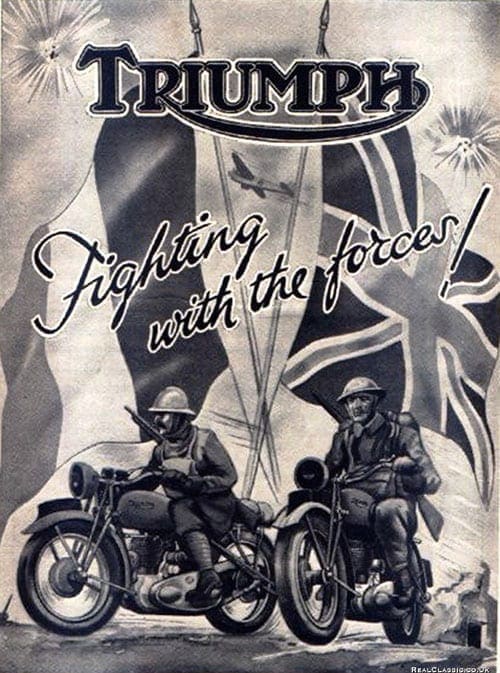

Many of the members of the armed forces had been taught to drive or ride as MT bods or Don Rs (Motor Transport drivers or Dispatch Riders to you civvies). So after the war there was a big demand for personal transport, and by mid-1946, motorbikes were becoming easier to come by. Despite the huge pressure to export, a trickle of new bikes appeared on the home market. They were a bit pricey around £140-plus, IF, that was, you could access them at all.

So most of us would-be riders were after ex-WD machines. These were being sold off by the hundreds at surplus depot. The snag was that they were being sold off in batches which could include non-runners, and had to be taken away by the purchaser. This limited the buyers mainly to dealers, of which there were thousands springing up in those days. They basically gave the bikes the oily rag treatment before flogging them – mostly under the £90 mark. The few ex-US Army bikes, mainly Indians, were considered to be a bit agricultural with odd controls, while the bigger, sidevalve BSA and Nortons a bit gutless but they were the cheapest so were bought as a last resort.

The machines of choice were in the OHV class, mainly 350s. The most sought-after was the Matchless G3L (the only one with teles apart from one or two ‘liberated’ small BMW’s), but the Forces hung on to a lot of the G3Ls until the 1950s so if you found one you had to act quickly before the off-road fraternity snapped them up. These gents were also on the ball when it came to sourcing surplus spare tele forks which were grafted onto all sorts of makes, usually to make trials and scrambles bikes. According to them, this operation plus a fatter rear tyre gave more ground clearance at a stroke.

My own intro to the addiction came when my mate, Peanuts, took delivery of a brand spanking new Triumph 3T 350 twin. Black and white paint job, polished ally chaincase and timing chest, no chrome but some nickel plate – gorgeous. Peanuts had been a very keen biker pre-war both in trials and scrambles, and had also mechanic’d for his mate who raced Excelsiors in the Manx GP. As well as the 3T, he also bought a new BSA B31 off-roader which came with teles, with a solid back end but no lights, horn etc. These were only sold to bona-fide sportsmen and he had had to get a letter of endorsement from his club secretary before he was allowed buy it.

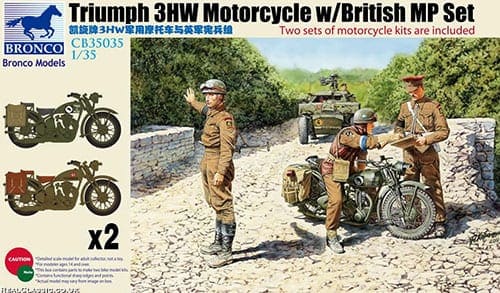

He trustingly taught me to ride the 3T on the airfield so I was bitten and had to have a bike of my own. I naturally asked his recommendation. He told me that whilst serving with the Desert Air Force they found that the bike that survived the desert by far the longest was the Triumph 3HW, hence his new bike choice. The desert conditions not only finished off the rest of the British bikes fairly quickly but also the German, Italian, American and French ones. We came to the conclusion that the 3HW’s durability came from a combination of several things.

Like most of the bikes made for the WD, the Triumph was a rehash of a pre-war model, the 3H. In Triumph’s case they were a late starter due to the factory being blitzed just as they were due to start producing their WD twin. The 3HW cylinder head became a one-piece iron casting with easy access to rockers and pushrods. Routine maintenance was a doddle. The gearing was lowered, the instrument panel was deleted from the tank and an air filter could be bolted there, in about the same place as the later Triumph tank grill. From the filter a large flexible tube went back and down. The back off-side corner of the tank near the saddle cut-out was removed and the tube passed down there to the carb.

We thought that the headlamp, speedo, steering damper cluster deflected a lot of the crud from the filter in its position lower down the tank and thus gave it a working chance. I was sold and looked for one to buy. There were not many about. Out of their production run, a large consignment had allegedly been sunk on the way to Russia and big shipments had gone to the Near and Far East. Of the ones for the Home Forces, apparently the Royal Navy had grabbed quite a lot for their WREN D/Rs as they were light and small which suited me (the bikes that is – on second thoughts, probably both). I eventually found and bought the bike and I became a Triumph man from then on.

The 3HW wasn’t cheap by the standards of the day – I coughed up nearly £100 OTR which cleaned out my RAF gratuity and savings but the dealer thought the 4000 miles on the clock were genuine, which proved true. He also explained the extra demand for these 3HWs. It was easy to change the gearing back to the pre-war Tiger 80 spec. Once the Forth Bridge-style pannier, pillion, prop stand and luggage rack were removed and ally guards installed, the bikes became a potent lightweight and versatile off-roaders, especially with Matchbox teles.

My RAF mates were all much of a mind to become mobile, so bikes proliferated and were generally hammered. We were riding on provisional licences as driving tests had not re-started. We were always welcomed at the local club events which at the time were just getting going again and were more in the gymkhana style with separate classes for road tyres and knobblies. I also used the 3HW as an occasional taxi to pick up mates from the local railway station and give lifts to the camp – best load was six – one on the bars, two on the tank, me in the saddle steering with my finger tips to bombing run commands, one on the pillion and tail end Charlie on the luggage rack. We made the four miles OK despite the drink taken…

We used the bikes to get home on weekend passes, petrol ration permitting, but the roads were quite rough in places Those who lived fairly near could do it on a 36 hour pass. So long as we were back for first parade Monday no one bothered. My oppo Slim (who of course was anything but) once went home to London on his Enfield which was a bit off-colour. He was missing late on the Monday to general concern and panic. He eventually arrived on an HRD Vincent. I think he was related to the Vincent clan. They were fixing his bike so loaned him the HRD. It had scared the pants off him. It was understandable, its throttle response compared to the Enfield had been mind blowing and he’d come back almost all the way on slow-running. I was told it was ‘nationalised’ as part of the MT section for the rest of the week and got a good workout on the runway and peri-track. His bike was delivered that weekend and the Vincent collected, but how the extra mileage was accounted for we will never know….

Next time: being demobbed, another Triumph, and the arrival of swinging arm suspension