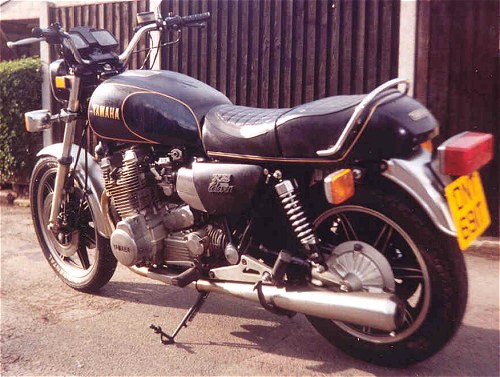

Honda and Kawasaki fours tend to grab all the glory, but Steve The Toaster reckons there’s a very strong Yamaha contender for Best Japanese Classic Bike…

Some things are just right. Design parameters can be spot on from the word go: the engineers who build up a first prototype can be on a high that day, the moon will be perfectly in conjunction with Mars, you know what I mean. It’s the like the difference between two pairs of leather motorcycle jeans. One will be saggy round your bum and be way too long, another will fit perfectly and feel snug all round.

The Yamaha team who designed the 1.1S were on just such a high that day. Here is a bike which is heavy and long, yet once rolling feels no worse for its size than many other UJMs, like the GTR1000, GT750, GS850G or CB750. All the big bikes of around this era had similar mass and power, a few having a bit more than others. You may have heard the term ‘All men are equal – although some are more equal than others.’ Well, a similar thing applies here.

The 1.1S made 95bhp at 8000rpm, which it delivered to the back wheel by my favorite system, the shaft drive. This is a match made in biker heaven, as you can do oodles of miles and have no maintenance to do after them. There were a few Jap Four shaft drive bikes to choose from around this time, though only Yamaha offered theirs as a ‘custom’ (the 1.1S) as well as a ‘straight’ road bike. They also produced the Martini ‘replica’ with a fairing and ‘jolly’ paint scheme, although I was never sure what it was a replica of… (In all fairness, Martini do sponsor a whole lot of racing). The American market got the ‘Midnight Special’ – but it wasn’t as good looking, for my money.

One of the main beauties of the Yamaha was its relatively low seat height of 31.5-inches, not too tall considering we are talking about an 1100cc motorcycle. I could get both my feet on the floor – and far more easily than on the CB750 of the same era. The GTR1000 was taller, and had a more top-heavy feel to it.

The low riding position, allied to the interface between the clocks and the seat, combined to give short people like me a reasonable amount of wind protection when traveling at speed on the 1.1S. I did a trip from Invermoriston, on the west bank of Loch Ness, to home in Bedfordshire, about 570 miles, in a day. This may not be an awfully long distance to someone used to spending all day on the saddle, but what surprised me was how relaxed I felt after such a long journey. The windblast mainly rippled over my head, making for a relaxed ride.

The strong motor would cruise really easily at ninety all day, and the roll-on from there was astounding. Cars sitting on my back mudguard just fell away, no matter how hard they tried to keep up.

The 5-speed gearbox was a delight to use, the only problem ever to raise its head was the fabled ‘second gear gremlin’. This usually appeared after about 20k miles – exacerbated if the engine oil was poor quality and not changed regularly enough. It would jump out of second if you hammered it up through the rev range. Eventually, third would go the same way, also at about around five thousand revs. No matter how carefully you went into second, hard acceleration would have it pop out well before the red line. I had heard of this on other 1.1s too, but as it pulled so strongly in all gears at low revs, I never let it bother me. The action was smooth through every change and not affected in the slightest by the shaft drive.

Shaft drive is one of Yamaha’s finest points, one they have mastered still use with the 900 Diversion. Why on earth the cursed the 600 Diversion with a chain is a mystery to me. They would have sold them by the boatload to despatch riders had they made it a shaft drive, like its bigger brother. The 1.1’s shaft was smooth and trouble free, in 30,000 miles it was totally ignored and worked smoothly and faultlessly. I never gave it a second’s thought!

The nice alloy wheels, black paint work and minimal chrome made it an easy job to keep the XS nice, but the black engine paint peeled off after two winters. The exhaust had already been replaced with an after-market four-into-one, but I detected no flat spots once I’d sorted out the four, 32mm Mikuni carbs. These had rubber diaphragms in the tops, and had perished to the point that they had splits in them. The bike ran, but was painfully slow to accelerate. This is why I’d bought it so cheap! The pathetically small bits of rubber cost an absolute fortune, somewhere in the region of sixty quid each. I needed four. Oh, I could have smeared silicone sealant over them and flogged it on, but that’s not really my style, besides, I wanted to unleash the full glory of the power of the bike. So with heavy heart and lighter wallet, I bought the damn things and spent an afternoon fitting them. Later on I was to discover that some car items are similar and cost a mere fraction of what Yamaha have the cheek to charge.

The transformation was immense. What had previously been a slug became a jet bike. It didn’t matter what gear you were in, how many revs you had dialed up, twist that throttle and away you go. It obviously had spots in the rev-range that were better than others, but from two grand up it flew — in any gear! My favorite game was top gear roll-on. I could lug around at anything between 25 and 120 in top, and just use the wall of torque to get me around.

On the smooth roads in the Scottish highlands, I got to unleash the power on some beautiful long, sweeping roads. This bike ate the miles and never flinched at how hard you accelerated. At around 550lb dry, it was a heavy old beast, and the frame was not really up to the modern stuff we are blessed with today, so you do have to make allowances when riding this and other bikes from this era. If you treat it like a modern bike then you will end up on your ear for sure. The current bikes run on modern rubber and have a frame that copes with their weight and power, and its chassis is where the 1.1S was let down by the technology available at the time.

You do have to ride it with confidence into corners as any backing-off will have it wallowing around like a camel in quicksand. It rewards a well set-up line, and driving it hard out of the corners is OK if the road surface is good as there is a lot of torque available at the back wheel. I had enormous forty-litre a side panniers on the bike for my Scottish holiday, with tent and sleeping bag strapped on top with a tank bag for good measure. It didn’t seem to affect the handling in the slightest, but I do remember removing some mirrors from cars as I fed my way through traffic on the way there!

Fuel consumption is a subject best not dwelt upon, you don’t buy a massively-engined bike like this and expect to get 60mpg. In fact, around half that figure would be what you might anticipate to get with some spirited riding; the only way to ride an XS Eleven. Having a decent exhaust and well set up carb bank will help a small amount.

|

The brakes weren’t bad for the era, twin 298mm discs at the front with a third at the back, but aren’t the tyre-squealing anchors you get now — and with the tyres that were around then, it’s just as well. Although there is nowt stopping you from updating the front end to something stronger with better brakes, it would rather spoil the originality of the bike, with those twirly LC style wheels and the handlebar fairing, which mine had unfortunately lost along the way. The other main peccadillo was the crank end float. More than a click backwards and forwards — then walk away. It’s easily checked by removing the left hand rotor cover and giving the crank a yank back and forth. On a thirty to forty thousand miler, you will get a small click but any more than that, well, it’s your money you are risking. Check the oil pressure warning light at low revs… wind the tickover off a bit and see what happens! If it flashes on and off as the motor turns over, it may not be long before Mr Bank Balance gets a kicking. Most XS1.1s will have aftermarket exhausts fitted by now, watch out for the Mickey-mouse studs that secure the header pipes into the head. They are rubbish quality and have been known to corrode to nothing in a couple of years. The electrics were good, they had no known problems, but the sheer age of the bikes may mean some corrosion will inevitably worked its way in somewhere. Also, where the wires go around the steering head, all that movement over twenty years must take its toll. If the bike doesn’t start on the button, or something electrical doesn’t work, be warned. Most should have steel-braided brake lines as the originals must have perished beyond usability by now! |

XS Yamaha stuff on eBay.co.uk |

Mine had the omnipresent Pirelli Phantoms fitted (19-inch at the front; 17-inch at the back), but then just about every large Japanese multi had the same tyres in those days – they were the tyre of the moment. I had no complaints in that area but then I wasn’t foolish enough to think that a bike of such voluptuous performance and proportions was going to track as well as a bike half its weight and power, like, for instance, a TZR250. It was a sports tourer, with more emphasis on the latter part of that equation, and should be treated with the respect it deserves.

There are a lot of owners’ clubs, and not just a few specialise in the XS1100 range, as the bikes are almost as popular today with their owners as when they were in the current catalogue. I’d have another one like a shot, if I could find one with low enough mileage, good diaphragms (spotted a website specialising in these – what does that tell you?) and not too silly an asking price. Sadly, I have been unlucky in my search, and so had to substitute a Guzzi Califonia instead as my next go-anywhere, shaft drive, fast motorway bike. If you see an XS1.1 in good condition, and it suits your requirements – you want a large, fast ungainly tourer — then grab it. You will not be disappointed. ‘Muscle bikes rule OK.‘ The designers knew how to please!