In the 1970s Dave Minton first greeted the idea of a high-speed, high-mileage 750cc parallel twin with suspicion, but he was fast won over. Here’s how, and why…

As a working motorcycle journalist, by 1971 I had become accustomed to abandoning test BSAs, Triumphs and Nortons by the roadside. The build quality of these final products of the British industry was, by this stage, simply appalling. So when Roger Slater offered me an SF 750 to take to the Laverda factory in Breganza and back, my enthusiasm for the trip was riddled with doubts about reliability. Roadside rescue services for Continental visitors then were unknown; one rode alone with one’s spanners.

To reduce the tale of a grand ride to its essentials, I arrived at the wrought iron gates of Breganze’s only hotel on a parallel twin which had been thraped to within an inch of my life (plainly not its!) for the entire and non-stop trip. It had remained stable at all speeds and finished the 800 mile ride as externally dry as when it started, braked as well, ran as sweetly, started as quickly, idled as regularly and was, blued pipes apart (‘They all do that, Sir’), undeniably less ruffled than I. The return trip home was as memorably uneventful.

It is perhaps impossible to adequately explain the rarity of such an experience at that time. Other big modern bikes entering the market could manage one of two of the essential constituents needed for a successful, very high speed trans-Continental ride, but nothing else in my experience encompassed them all. I was gobsmacked, and promised myself that one day I would own one.

So what was it that made this trip, and many others like it, possible on a Laverda parallel twin when it was not possible on the British machines of the era?

Laverda had been producing motorcycles since 1949 and they were sporting enough to encourage Pietro Laverda to go racing. From 1951 to 1960 Laverda singles won their classes in the long distance races, then so often that they almost became Laverda benefits. One year Laverdas filled the first 15 places in the Milano to Taranto event. Then, in the last year it was run, Laverda entered its brand new 750 GT in the Giro d’Italia and won the 750 class outright.

The Laverda family had no interest in Grand Prix racing, believing wholeheartedly in the policy of improving the product through road-focused competition. One of the great movers behind Laverda racing was Massimo Laverda, elder son of Pietro, who in this period was an engineering student at Milan. Realising the potential of his company’s new twin, Massimo urged Luciano Zen, Laverda’s head of engineering, to tweak the GT into the S. The company’s team of S bikes won every endurance race they entered in 1970.

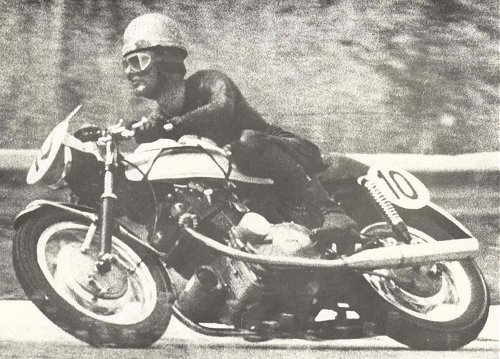

Racing victories convinced Laverda it has a winner on its hands and, in parallel with the development of the SF sportster, it produced the SFC racer. These 135mph, bright orange twins set an endurance racing pace through the 1970s that won them a list of events too long to relate. A great deal of this racing experience was incorporated into the SF sportsters. In fact the SFs proved so race-capable that they also gave a fine account of themselves in production formula events. While they lacked the angel-flight ease of a Ducati around bends, they handled superbly and were utterly dependable in all technicalities – especially electrics.

The curse of Italian electrical systems followed hard on the heels of Lucas’ deservedly abysmal reputation. But Laverda’s twins employed no Italian items whatsoever. Their 12-volt 150-watt belt-driven dynamo was by Bosch, as was the headlamp and entire ignition system, while the massive starter motor was especially made for Laverda by Nippon Denso, as was most switchgear. It was bulletproof.

So, by the time the 750 SF was revealed to customers in 1971, the Continental audience had awakened to the superior material and the dynamic qualities of these twins from Breganze. In Holland, Laverdas outsold Honda fours as a consequence of the twins’ endurance racing success. The racing winning S of 1970 became the race-shop-built SFC and the sportster 750 SF.

The SFC adopted the 744cc (80 x 74mm) engine of the preceding S, which with 60bhp on tap at 6000rpm delivered a top speed close to 112mph. The frame, though, had been developed from the original to shift the centre of gravity further forward, fractionally lower to improve axial stiffness.

This was also the first time that Laverdas own brake had been seen. The big 9-inch 2ls drum replaced flawed Grimeca units. So pleased was Laverda with its own brake that it dubbed the new models ‘Super Freni’ or Super Braker, while the C of the endurance racers signified ‘Competizioni.’

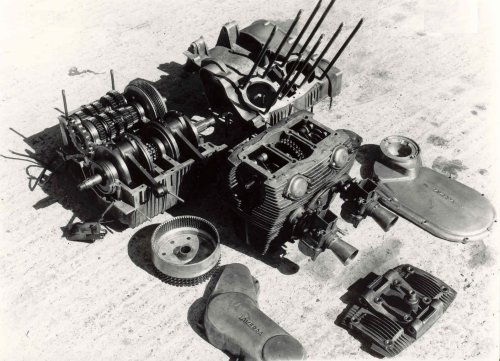

Imported into Britain by Slater Engineering and sold crated in knockdown format as kit bikes to beat purchase tax,, these first 750 SFs cost £685; a Honda CB750 was £680. At 500lb fully tanked they were heavy machines, but with good reason. Laverda employed their massive fabrication to resist vibration, as well as to ensure unprecedented high speed stamina. No other engine then made could match the massive over-engineering of the crankshaft which ran on five ball and roller main bearings.

The frames beggared the imagination with equal facility. Familiarly described as being a ‘load bearing’ frame member the engine in practice is no such thing, although it hangs from the frame. Four massive tubes flow serpentinely from the steering head, two dropping down to the gearbox and swinging fork pivot, and two continuing horizontally as top-run sub-framing. The heavy gauge of the tubes endows the frame with a weight probably unequalled in tube steel frames and this, no less than the mass of the engine, contributes to the comparatively low vibration of the models.

The significance of the frame’s mass may be gauged by Fritz Egli’s disappointment over his SF and SFC engined machines, which in his lightweight chassis vibrated sufficiently to dissuade him from pursuing a commercial future with them.

As 360-degree parallel twins they were assumed by a cynical generation of twin-rattled British riders to vibrate. In practice and correctly serviced, by the standards of the day, SFs did not vibrate and could be ridden all day without cracking up, leaking oil or white-fingering their riders. Moreover they accomplished it reliably and with gratifying high speed stability, rare prizes then. Noisy brutes, though. Ah…

You will recognise the early 750s by their BMW R69-style Bosch headlamp, Smiths instruments, ‘square’ 1.20inch Dell’ Orto carbs and separate twin exhausts. Early models were fitted with the S’s humpy tank and its rubber knee pads, later ones came with the new big and plain long tank.

Some folk swear that these drum brake models are the best of the series, thanks to a combination of small carbs, a semi-sporting camshaft, slightly lightened flywheels and less of an arm-stretching riding stance.

At the time they were popular enough that Laverda were unable to meet demand, so little was changed for the models’ second year. There was an option of a race-styled seat with a lockable box in its back-stop, and the instruments changed to Nippon Denso. On a good many of these the ‘S’ trademark of the plainly Suzuki-intended parts had been scarcely overprinted. The accuracy of the instruments compared to Smith’s eternal dance to the music of anything but speed was a revelation.

By this time these Laverdas had been recognised and in Britain were beginning to benefit from the attentions of a small but discerning group of riders, typically more usually associated with Vincent, Velocette and BMW machines.

No serious design flaws or performance faults had arisen. What vibration did occur was an effect in inadequately tightened engine mounting bolts, carburation or ignition tuning, and a few hard-ridden bikes cracked their front mudguard stays.

The legend of Laverda’s ‘Big Boy’s’ clutch had gone before it and Laverda took inverse pride in meeting the challenge. In fact a re-routed cable and good lubrication usually cured half of its weight fist-resistance. By this time, as befits 1972, Laverda was selling the SFs in an astonishingly glamorous range of bright metallic colour schemes and offering both dual and race-styled seats. As the bikes were black and chrome apart from tank and sidepanels, a new owner simply picked his colour and awaited dealer fitment.

However, the world was rapidly changing around them. The CB750 was undergoing major rolling chassis revitalisation, while Kawasaki seemed determined to prove to the world that 900cc four-pot power was all. Ducati were snapping (somewhat erratically) at Laverda’s heels and BMW bikes were going great guns. The 750 SF would need a boost to stay competitive.

Next instalment: SF1 to SF3, buying and riding today

Laverda twins. Better than the triples?