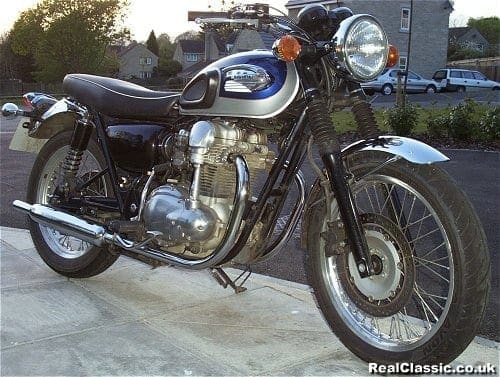

Jonny Wellard wants to know if his Kawasaki W650 is groovy and fab, or just grubby and sad. People ask him; ‘what’s the point of having one of those when you could buy the real thing?’ And he has an answer for them!

That’s the nub of the issue isn’t it — Kodak or Constable? Well, as I have a W650, I have enjoyed more than a few ‘Kodak Opportunities’, and as I have also owned a ’71 Triumph Daytona, a couple of ‘Constable’ moments (thank you for returning that exhaust pipe, Officer… I never even heard it fall off) too. I suppose it is down to the distillation of ‘ownership’. What are the motivations behind owning a piece of Brit heritage? I am tempted to make a list — in no particular order:

1). Sheer joy of ownership. This is all about simply ‘knowing’ (and letting others know) that you have an old Brit. The quiet pride when you let slip that you have an old banger. It says volumes… here is a man who appreciates English craftsmanship, who is handy with his hands, who knows quality.

2). Membership of the elite. Goes with number 1 above really, but there is a whole social scene attached to the interest. You start with the closeness of the one make clubs and work out to the general Brit enthusiast. With many owners nearing retirement age, this is an absorbing way to spend free time.

3). The riding experience. Now we get down to it. A good Bonneville is a thing not only of beauty. It’s a visceral exciting motorcycle. It is so often forgotten today that not all Brit twins were plodding about in some strange, slightly surreal landscape littered with lamp-posts (to count the firing pulses) and torquing their way up 1-in-4 hills in top at 2000rpm.

I was forcibly reminded of this when I happened across an old BBC sound effects record. On the sleeve notes was the enigmatic listing; ‘Motorcycle starting and pulling away’. Closer examination revealed that the bike in question was a 650 Triumph. Whoever was riding it had not been told to ‘keep the revs down because it has just been rebuilt.’ Oh no! This Trumpet was really singing. I reckon the rider didn’t shift up until at least 6000rpm, right through the box, and it was a glorious aural affirmation of the way those bikes used to be ridden.

This last one is the whole point of the W650. Kawasaki did not have the future of  the company riding on the market acceptance of the bike when launched, so unlike the anesthetised new Hinckley Bonneville, it didn’t have to be many things to many people. Instead they concentrated on making the bike deliver the same emotive ride as those old bikes had. I’m not taking about a 40 year jump into the past here, with all its attendant woes, but the essence of how those bikes felt — the vibe without (most of) the vibration, if you will.

the company riding on the market acceptance of the bike when launched, so unlike the anesthetised new Hinckley Bonneville, it didn’t have to be many things to many people. Instead they concentrated on making the bike deliver the same emotive ride as those old bikes had. I’m not taking about a 40 year jump into the past here, with all its attendant woes, but the essence of how those bikes felt — the vibe without (most of) the vibration, if you will.

When I first started mine — and so enamoured was I, that I had paid for it before I heard it or any other W650 actually running — I experienced one of those almost shockingly vivid flashbacks. The cadence and rhythm of the 360 parallel twin motor was so familiar I couldn’t help but smile. It was like smelling an old girlfriend’s perfume after many years have passed. Whoosh — you’re back there. Funny thing, the memory.

Anyway. The W650 put its power down just like my Daytona, a muscular grunty bottom end, not the comedy lunging of a big V-twin, but a poised, torquey surge that promised of things to come. Hit 6000 on a W650 and it comes on the cam just like my old Daytona did at 5000. The engine note hardens, the bike starts to move under you, and the world suddenly becomes a better place.

The view from the saddle is similar to a late 1960’s Triumph, with that chrome headlamp and proper clocks just behind dominating your view. The ergonomics are just the same, with the later, lower bar fitted (the first UK W650s had a higher, wider ‘export’ bar which did not generally go down well amongst UK riders). There is no doubt that the designer had a mate with a ’65 Bonnie, but there are shades of Norton, BSA, and others within the rather well executed shape.

|

The big question is: how much of those old bikes can you leave out and still have that experience? Well, although Kawasaki left a little vibration in, peaking at around 3500, after that speed everything smoothes out in typical turbine smooth Japanese style. A downside? Emphatically no. There is nothing nice about excessive high-speed vibration — and very few Brit bikes were free of it. It breaks things, hurts your body, and generally messes stuff up. W650s are remarkably reliable, and seem impervious to sustained high revs. The forks and suspension work very well, with a plush, well damped ride and good control over bumpy surfaces — not in that ‘isolated from the world’ modern way, but like a Bonnie with really good damping and soft springs. |

W650 stuff on eBay.co.uk |

Imagine if you will this unlikely scenario.

You own a ’65 Bonneville, your favourite bike. One day the Bike Fairy appears. With one stroke of his wand he puts a spell on your pride and joy. In a flash he eliminates the rather harsh ride you get from the old suspension. As he walks around the bike, a careless tap chromes the mudguards, and a bit of magical blow-by ricochets onto that dodgy front drum, turning it into a subtle but fade-free disk. He zaps the motor so it is now safe to 7800rpm every time, grunting a guarantee that no matter how hard you ride it, it won’t break, leak, or otherwise let you down.

The Bike Fairy passes a heavily tattooed arm over the electrics so you now have a brilliant halogen headlamp, indicators, a bright brake lamp, and a discreet clock next to your oil pressure light. He lifts his eye patch briefly and a baleful glare forms an electric motor and press-button out of pure photon energy to complement the kick-start. He links the efficient, maintenance-free twin carbs so they don’t go out of synch, fits a powerful electronic ignition — and hands you the ignition key (which now also fits the steering lock, seat lock and helmet lock), before disappearing in a fragrant cloud of Castrol R.

Your Bonneville (already nicely run-in) now makes a healthy 45 rear wheel bhp. It will take you the length and breadth of the British Isles as easily as popping down the shops. You can now thrash it for as long and as hard as you like and it won’t care. It doesn’t vibrate at speed, and nothing falls off. Night riding is a joy, and you only have to fiddle with it at weekends if you want to. The best bit though, is that it still feels the same…

If you would love to have a Bonnie like that… tough. You can’t. But for a couple of grand you can get a clean, low mileage W650…

Your beautiful, original work of art can remain for high days and holidays. Instead of devaluing it and wearing it out, you now have an everyday bike that demands little from you, and offers the spirited ride your much cherished classic may no longer be able to afford to give you.