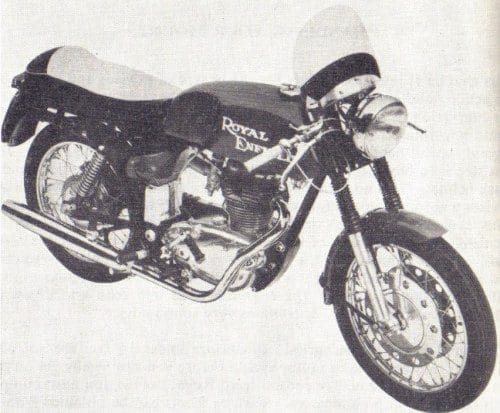

Kel Boyce lusted after a little Enfield back in the 1970s. Then he bought one. Then he took it apart. And then… it had to be put back together again!

It was winter, so I started with the engine rebuild, as the lump could be easily accommodated on the kitchen table.

The crankcases were helicoiled (or bushed) where required, the crank-pin reground, and new main and big-end bearings fitted. The conrod looked fine, except that a careless gudgeon pin extraction had left a score through the unbushed small end eye (more of this later).

The weird oil pump appeared sound but, as the design seemed suspect, I bought a new one from Jack Gray for a tenner. The pump body should be lapped to its housing with ‘T-Cut’ (not metal polish) and the merest trace of gasket sealant should be applied between housing and crankcase. Too much and the oilways will be blocked and then (as too many owners have discovered) it’s goodbye crankshaft.

The cylinder was rebored and a new piston fitted along with new valves, springs and guides. The valve collars are aluminium and, although they look dodgy, I’ve yet to hear of one giving out. New primary and timing chains went in, together with new oil seals.

Now, the GT (and Super 5) gearboxes are renowned for their false neutrals, around 10 in all, so it was with this in mind that I took great care to minimise slop in the outer linkage and adjust the inner ratchet to give the recommended clearance. I also recut the battered gear dogs.

Incidentally, the first time I saw the crazy inner linkage I laughed as loudly as when I saw the oil pump. On the plus side the 250 REs have cassette-loading gearboxes that antedate GP ones by about 40 years.

As for the clutch, this was always adequate for its purpose but I thought it best to fit new friction plates and springs. I’d heard that some people fitted an extra plate for good measure but for road use this seemed unnecessary, unless you really wanted to build up your left arm muscles. I checked for buckled plain plates, bearing in mind that two of these are intentionally ‘dished’. The clutch is another one of those peculiar RE features, the springs being mounted outboard of the clutch and sandwiched between the clutch cover and a circular retaining plate. Don’t laugh, but the mechanism resembles a North Sea oil platform!

|

|

Random Continental Bikes on eBay.co.uk |

The final assembly I carried out with great care, for I intended there to be no oil leaks (legend has it that, in the 60s, riders would put a drip-tray under the nearest Enfield and collect a couple of pints of free lube overnight!). Thank God I had the help of something unavailable to 60s riders – silicone sealant!

The engine / frame layout is similar to the 250 Ducati but I’m not certain which predates which. Furthermore, the Honda 250 RS single must surely be a copy of one or both of them.

In my case, I merely needed to shot-blast and re-stove the frame. The swinging-arm was bent back into shape and re-stoved whilst the steering-head bearings were good enough to go back in. The alloy fork sliders were re-polished, after the graunched one was cleaned up, and then reunited with their original stanchions.

The upper alloy fork yoke-cum-clockholder (or ‘casquette’) was polished to its former glory and a new blue-faced speedo fitted alongside the original rev-counter.

Secondhand mudguards were then fitted, the front being more deeply valanced than the GT version and, therefore, more weatherproof. I believe this came from a Continental.

The rear wheel was rebuilt with a new rim and spokes but I replaced the 18-inch front with a 17-inch from a Crusader, the reason being that I got it for eight quid, complete with tyre. Unfortunately, the wheel also had a WM-2 (not WM1) rim, so the bike was robbed of its normal rakish GT look. I fitted new shoes to the front brake in the hope that it might actually work (mug!).

Jack Gray was the source of most of the special GT parts, including the seat, exhaust system, flyscreen, battery / coil cover, and headlamp bracket. The GT headlamp bracket is a crude job (not a patch on proprietary chrome ones) as is the gear-change (outer) linkage and both appear home-made. The flyscreen serves two purposes – to reflect engine noise back to the rider and to provide somewhere to tape your travel route. The rubber gaiter between the chainguard and crankcase was unavailable in the late 70s, so the bike was always minus this particular piece of kit.

Needless to say, the new paint on the fibreglass tank bubbled up after a few weeks, even though it went on over a sealer, whilst the grey handlebar grips I fitted, looked so blooming stupid they only lasted two minutes before hitting the bin.

Going on to the electrics, well, here I made a bit of a boob and restored the old 6-volt electrics, instead of going for 12-volt. Anyhow, the ageing and brittle wiring loom was replaced and new rectifier, brake switch, battery and headlamp fitted. The latter made little difference as, after thirty minutes night-running, Joe Lucas (Prince of Darkness) would strike and the bulb would gradually fizzle out in emulation of a dying glow-worm. Conversely, the battery was prone to boiling during daylight runs.

It was all coming together. Soon, I would actually have to use the thing.