Ariel’s Arrow was certainly an oddity, and it is most definitely an old British bike. But is it a genuine classic motorcycle? Paul Friday doesn’t really care, because his Arrow was certainly the worst bike he’s ever owned…

It wasn’t all the bike’s fault. I was the previous owner from Hell.

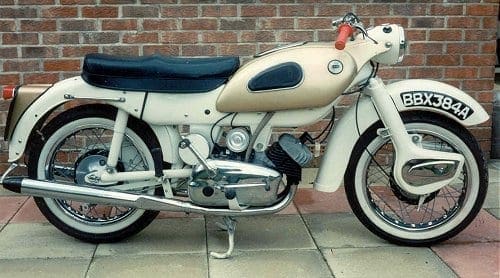

I was young and free of common sense and I wanted a bike. A mate at college had a rare example of solid British pluck in his shed, that he could let me have for more than I could afford but less than I feared. It was an Arial Arrow — a full learner-legal 250 twin of throbbing power and glorious speed. I went and saw the huge beast in his dad’s garage, and a deal was struck. He hadn’t finished building the bike yet, but to my innocent ears it sounded ideal. He was putting it together from the best bits of three engines and one frame. He would let me have all the unused bits as spares. It stood glinting in his shed, a vision in pale blue Hammerite. I was in love.

My parents, typically, thought my intended was unsuitable. I wheedled and whined, and eventually got parental approval (or at least surrender) and the cash.

I was a biker!

Of course, I had no insurance, no crash helmet and no MoT. No matter, I pushed it the few miles home. I went back again with my Dad in his car and filled three potato sacks with spares and oddments. There was a complete workshop manual in the pile, and lots of bits still in greasy paper. I was so happy. I filled a can with petrol at the garage and gave it a couple of shots of oil from the two-stroke dispenser. With my father watching, I went through the starting drill from the manual and kicked it over.

It fired immediately and snapped the crankshaft.

Anyone that has ever pulled an Arrow apart will know that the crank was made in two halves, joined with a taper and located with a Woodruff key. My mate hadn’t tightened the bolt through the middle, so the taper slipped and snapped the key.

This should have warned me what to expect, but hey, I was seventeen (if you know what I mean).

For some strange reason my dad had withheld half the money until the bike was working, so my mate soon scurried over and gave me my first lesson in stripping the Arrow engine. I must admit to being impressed with the design – taking the crank out was a quick and easy job, and could be done with the engine still in the frame. We had no spare Woodruff key and only my Dad’s selection of hammers and bent screwdrivers to use as tools, so we bunged in one of the spare crankshaft halves from my potato sacks and slapped it all back together.

With the engine running, I scraped up the £30 for third party insurance and hit the road. Very nearly forever. It was my first lesson in looking over my shoulder before changing lanes. I fitted a mirror with the world’s longest stem and burbled around in my turquoise anorak and yellow open-face helmet.

I rode the bike to college every day. It was only a couple of miles from home, so I usually got there. I was so proud when I parked it in the big shed with the other bikes. It sat at the end of a row of Nortons, Triumphs and Hondas, like some malformed offspring of a scooter. I’d never been shown how to start a bike, so I developed my own method of snapping the throttle open as I kicked it over. As a result it never started first time. Or tenth. In fact, I can’t remember it ever starting until I was lathered in sweat. Being young, it never occurred to me that it may not have been my anorak or my complexion that kept the girls away.

Even so, I lost the use of my legs and rode everywhere. And everywhere I went, I left a trail of small parts and fasteners. For something as smooth as a stroker twin, an awful lot of bits seemed to vibrate off the Arial. The points cover went first. The examiner made a few cruel remarks about the way the points were sparking in the rain when I took my test, so I glued a yoghurt pot over them and painted it black.

Then the air filter left me. I saw this as a Stage 1 tune, and removed the rubber trunking from the carb as well. Being a roadwise Biker Dude, I knew I needed filtration, so I used an old pair of my sister’s tights and a few turns of insulating tape to fashion a gauze filter. The petrol melted a big hole in the mesh and left just the tape, which got soggy and fell off.

Then the engine started making a strange grinding noise and lost power. After checking everything else, I removed the alternator cover. The rotor fell out on my foot. The rotor bolt seals the end of the hollow right-hand crankshaft half on the Arrow, so the right pot had been making no crankcase compression. This was big time serious, but luckily my Dad found a tap of the right size to reform the thread, and I put the bolt back in with a long spanner and a lot of threadlock.

The rest of the threadlock I put in the toolkit tray, which sits in the top of the dummy tank. It leaked, and glued all my tools and spare spark plugs together.

Then the coils fell off. This didn’t matter, as they live inside the hollow box frame. Getting them back into their spring clips requires a very slim hand with two wrists, so I just left them to rattle about.

Being young in the ways of the world, I used to take the bike apart just to see why it was running so well. But I was afraid of stripping threads. As a result, I never tightened anything properly. I’d had the front wheel out for some reason, and the handling afterwards was very odd. The bike was all over the road unless I used the front brake, in which case it steered properly again. After a week of secretly doing my own laundry, I discovered the front wheel spindle was loose and the wheel was flopping between the fork legs.

The twistgrip had a sharp edge on the drum, so it used to fray the nipple off the end of the throttle cable. Each time it happened, I tidied up the end and re-soldered it. The cable became so short that I couldn’t turn left without accelerating. One of my usual morning rituals of running up and down the road to start the bike, it finally caught. I leapt aboard and braked hard to turn it round. I turned left. The engine screamed and filled the neighbor’s garden with smoke. I let go of the clutch and reached for the key. I did my first and only doughnut right on the end of our neighbour’s drive – the grumpy neighbour who always complained to my Dad about the noise I made. He wasn’t too impressed with the tyre marks, either. Or the smoke.

I’d put in some long nights in the garage trying to make the ancient wiring loom work. I got so fed up that I replaced one of the main runs with a length of three core domestic cable. It ran along the top of the frame, under the tank and seat. To a young lad with no money, this was a top bodge – I’d replaced three bits of nasty old wire with a single length of (free) three-core flex.

I was about ten miles from home when the edge of the sheet metal dummy tank cut far enough into the cable to start an electrical fire just under my crotch. I taped up the burned length (of cable) and propped the edge of the tank with a bit of cardboard, and all was well again in my world.

Around this time, I finally wore down a girl into going out with me. Her brother had several bikes, so her parents were happy to let her go out on the back of mine. Except I could never afford more than half a gallon of petrol at a time. I used to get my half gallon and a shot of oil at the beginning of the week, and take her out on Saturdays. We used to go to a pub out in the sticks, and I’d be stopping every mile and tipping the bike over to get the dregs into the carb. We always got home, but I have no idea how. At least she had a sense of humour.

I remember that I did just once fill the tank, when I took a mate (a different one) on the back to Guildford. This was nearly twenty miles away, so the investment seemed worthwhile. We got halfway there and the bike lost power. This time it was a stripped spark plug thread. We managed to nurse it on one pot to an engineering shop, who did me a helicoil on the spot. Probably to be rid of me.

It was after this epic that I left the bike standing for a few days. Come Saturday, I hopped on and thrashed it into town down the bypass. I noticed that the cars overtaking me had their lights on, which was strange. It was only when I got to the end of the long straight and checked the mirror that I realised I couldn’t see the road behind me. The oil in the tank had settled out, and the bike had been running on neat two-stroke with a dash of petrol. The thick blue fog covered both lanes of the bypass. I shot up a side turning, parked the bike and vanished for a while.

There was only one time in my ownership that the Arrow really showed its stuff. There were a gang of us with bikes, and one of the lads had a Suzuki 200 twin. He took a lot of stick for only having a Jap. The fact that his bike always worked, went fast and carried him more miles in a single journey than we made between rebuilds didn’t register. So, we were off down the pub for lunch, and I’d got the job of ferrying the bikeless one. He had my rucksack full of books, plus his own. We pulled out onto the main road, and the lad with the Suzy gassed it and made a run for the traffic lights…

I clouted the Arrow into first, grabbed full throttle and dropped the clutch. A pair of feet rose past my shoulders and over my head. I threw out the anchor and stopped in the road, in time to see my mate land on the back of his head and rebound into a forward roll. When the smoke cleared, he was clutching the back of my bike in an amorous crouch. When we finally got to the pub, he had ripped my rucksack as well as his jeans and jacket. Still, it must have been character forming, because he bought a BSA Starfire.

Finally sanity, and the need to spend more time with the girlfriend than the bike, began to intrude. I started looking for a replacement. A friend at college had a Raleigh Wisp moped for sale at £15, which sounded more practical than my wreck. On the way to see it, the Arrow lost the end cones off its silencers and got a flat rear tyre. Perhaps it knew. I made two new end cones from cut-down aerosol tins, and sold this rare example of solid British pluck to another innocent for what it had cost me (or rather, what it had cost my dad).

And if you look in a classic bike magazine today, there are people selling them for up to £2000. Just make sure you don’t buy mine.

So what’s the worst classic bike you’ve ever owned (or ridden)?